Caring for a child with food allergies requires knowledge and avoidance of parental diagnosis

Chicago mother Lourdes Craelius isn’t sure whether her 8-year-old son is lactose intolerant because she’s never had him tested. Her suspicions stem from hearing her son complain of bad stomachaches occasionally after consuming dairy products. And quite often, he refuses them because of the pain he feels after eating them. “It’s almost as if his body knows that he shouldn’t be eating it,” she says.

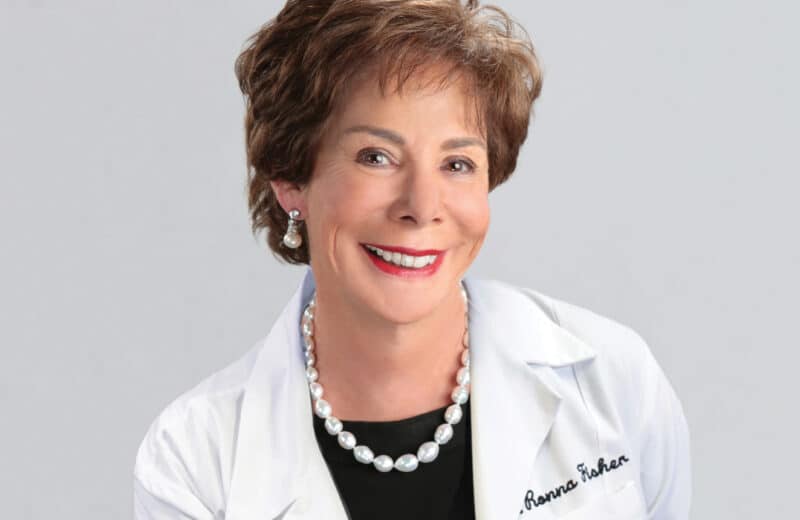

Situations like these are not uncommon for allergists to hear in their offices. Explaining the difference between allergies and having an intolerance to specific foods is a regular occurrence for many physicians and nutritionists who treat children for allergies. The primary difference, notes Dr. Laura Rogers, a Chicago-based physician with a specialty in the practice of allergy, asthma and immunology, is that one can be life threatening while the other can make you feel like you’re going to die.

A food allergy is defined as the body’s adverse immune reaction to a protein. The most common allergen proteins are those found in nuts, wheat (gluten), milk (casein) and egg (albumin), according to Mark Spielmann, RD, LDN, nutrition manager at La Rabida Children’s Hospital.

Classic warning signs of a food allergy include abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, rashes on the body and/or face, wheezing and swelling around lips or on face, adds Spielmann. Similar symptoms can appear for those with a food intolerance, making it sometimes difficult to know whether to react as if it is an emergency.

Dr. Keith Lemmon, a Glenview-based, board-certified allergy and immunology doctor, spends much of his time reviewing and clarifying issues, such as what constitutes a true allergy versus intolerance, and helps his patients and their parents learn how to read food labels, avoid food allergens and how to recognize reactions and treat them quickly and appropriately.

“I always advise that patients or the parents of food-allergic patients take [the] reading [of] labels and avoiding food allergens very seriously,” says Lemmon. “It is important to also be proactive. For example, when eating at restaurants, don’t be afraid to insist on receiving clear answers about a meal’s ingredients. Ultimately, you do the best that you can, but also always stay prepared in the event that an inadvertent exposure occurs, at which point you treat symptoms immediately.”

Rogers highly recommends anyone caring for a child with a food allergy know how to use an Epi-Pen (Epinephrine Auto-Injector) in case of an emergency. “You should use it on the way to the nearest emergency center so [that the] child can be seen immediately and monitored,” says Rogers.

Follow the rules: Read labels carefully

But knowing what to look for and avoid versus actually doing it is another story. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology reported a study conducted in Canada that found that consumers might not be as diligent about heeding packaging labels and warnings when buying food. This news does not surprise health practitioners, although it certainly concerns them.

The results from the study suggest that when certain noncommittal, precautionary statements are used, consumers often ignore them. “It’s difficult for parents to understand the labeling,” admits Dr. Ewa Schafer, a physician with a specialty in allergy and immunology at NorthShore University HealthSystem. She fears that some labeling is ineffective and causes parents to avoid buying some products because they are incertain whether the food will pose a risk.

In addition to the fact that some products may be produced in a facility that also produces other products with traces of the allergen, food manufacturers often change factories, so while a product may have passed the initial parental-check test, that same product may now be produced in a different factory. “Check the labels, even when you’ve purchased that same product before,” recommends Schafer.

Lemmon recognizes that reading actual ingredient lists can lead to confusion for many parents. However, Congress passed the Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act of 2004 (FALCPA), which requires that all food whose labeling is regulated by the FDA must clearly identify the food source of all ingredients that are—or contain any protein derived from—the eight most common food allergens.

When in doubt, don’t self-diagnose

Parents self-diagnosing their kids, like Craelius diagnosing her child as lactose intolerant, is an alarming trend that health practitioners are seeing. Schafer is noticing that parents are removing certain foods from their children’s diets before seeking medical advice because they think their children might be allergic.

“Parents are altering their children’s diet[s] without having the facts,” Schafer says. “This action may be depriving [these children] of nutritionally rich foods. If food is going to be avoided, it should be avoided for a [substantiated] reason.”

Spielmann agrees. “I find it disturbing that parents are voluntarily putting their children on gluten-free diets,” he adds. “Gluten is not a toxin; it’s not the enemy. Humans have relied on wheat for thousands of years.”

In Craelius’s case, she hasn’t had her son tested because she hasn’t felt the issue has been severe for him, and she notes that when he is not exposed to dairy products, he doesn’t complain. But now that he’s getting older and eating more of a variety of foods, she plans to speak with his pediatrician about getting him tested.

“I agree that if [parents] suspect that their child has any food-based sensitivities, to talk to their pediatrician and also take steps to ensure that they try [to] figure out what they are [in order] to help them manage it,” she says.

Planning helps children manage other issues

Schafer often finds herself helping parents not only manage their child’s disease in relation to their family’s dietary needs, but also suggesting how to destigmatize it in social settings.

“Food is a part of our society and our socialization,” Schafer says. “While it’s easier to manage the disease when children are younger, it’s different as they enter school and begin attending birthday parties or other celebrations. There are social implications to managing this disease, and most people don’t realize how much of an effect this has on children.”

To help children cope better and not put themselves in harm’s way, she recommends that parents prepare by having safe snacks ready, perhaps making cupcakes without eggs if the child has an allergy to eggs so that he or she can still enjoy a treat at a birthday party.

Shafer realizes that this advance planning takes time and effort, but the alternative may lead to a trip to the hospital or worse.

While diagnoses of allergies in children are on the rise, the positive news is that many children outgrow their allergies by early adulthood, according to Spielmann. Also, Lemmon is encouraged by new developments occurring in research labs.

While [the classic allergy shot is] very effective in its current form, researchers are constantly improving how the allergy shot—and in some cases, using drops under the tongue—regulates the body’s immune response,” says

Lemmon. “By combining different delivery systems and genetically engineering allergens, they are improving on this treatment’s efficacy and safety.” [email_link]

Published in Chicago Health Summer/Fall 2012