Some answers only reveal themselves after a person dies. For those paying attention, the information can change perspectives and save lives.

Pick any afternoon in the Illinois Medical District — home to multiple major medical centers — and quiet isn’t the first word that comes to mind. Traffic-logged highways encircle the area, and ambulance sirens wail regularly.

Yet, just a few blocks away from those institutions sits the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office. And on this gray, snowy afternoon in January, it is very quiet here, like most other days. This two-story concrete building is where people in Chicago and the surrounding towns go if they die in sudden or unexpected ways.

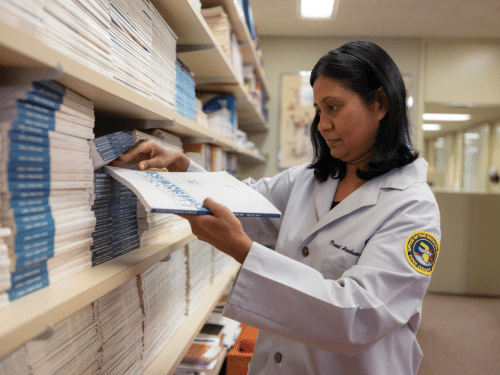

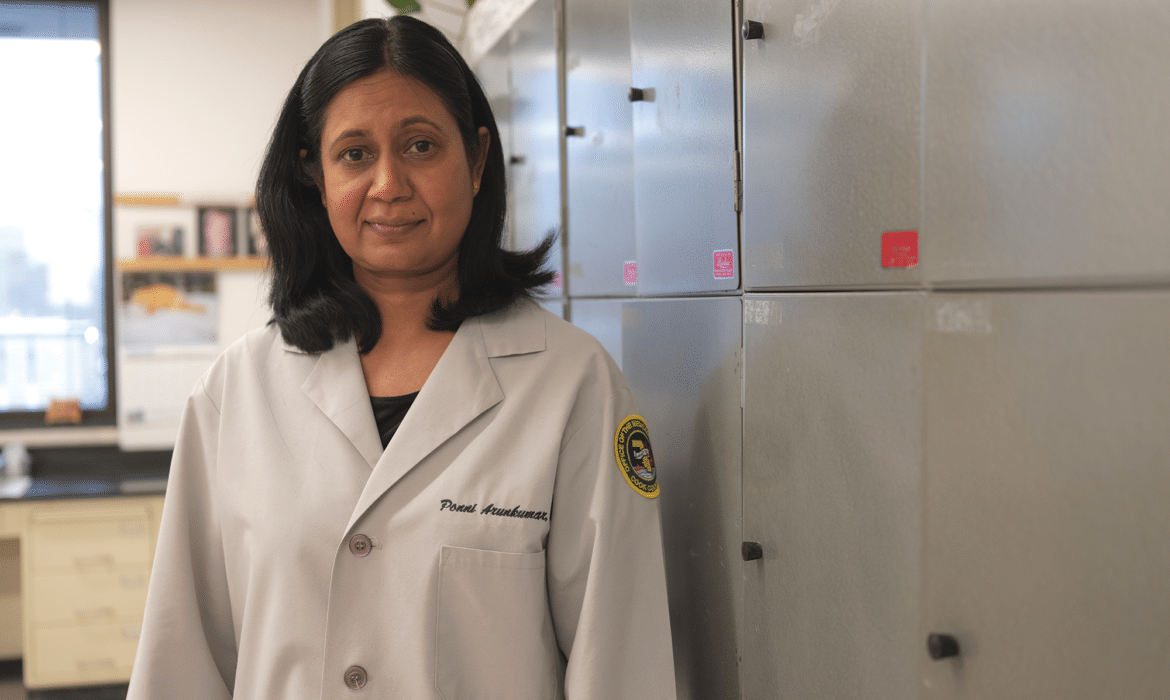

Chief Medical Examiner Ponni Arunkumar, MD, sets the tone. Shelves lined with pathology books and photos of her children fill one wall of her second floor office. Since 2016, Arunkumar, who has nearly 20 years of forensic pathology experience, has led the organization in an understated and self-assured manner. The deaths her team handles may be complicated, but Arunkumar knows exactly how to handle them.

“We are the patient’s last physician,” Arunkumar says.

Her office performed 10,443 autopsies in 2022, down from a peak caseload of 16,047 in 2020, but still significantly higher than the annual pre-Covid average of 6,200 deaths. In total, 47,077 people died in Cook County in 2021 and 52,298 in 2020.

The medical examiner’s office performs autopsies for deaths that appear to be unnatural, such as suicides, homicides, accidents, and unexpected deaths of young people.

“We take jurisdiction of any death that needs further investigation. We look closely at their front and back to look for foul play or trauma,” Arunkumar says. “Sometimes the trauma is hidden. We can’t see it externally.”

The office also takes on potential Ebola cases, mass fatality incidents, and deaths that happen in custody, such as with law enforcement or in a psychiatric ward. “For people who can’t take care of themselves, we want to see how care was provided,” Arunkumar says.

The medical examiner’s office publishes statistics online daily about what people are dying from, where, when, and how.

While homicides make the news, opioids have caused most of the deaths her office has examined, Arunkumar says. In 2022, preliminary data show that 1,750 people died of opioids in Cook County (though the number will likely rise to more than 2,000 once all analyses are complete). That’s compared to 934 homicides. In 2021, those numbers were 1,935 and 1,094 respectively. People age 50 to 59 made up the majority of opioid deaths in 2022.

The information the office provides can lead to more effective policies and treatments. “We give an idea of what’s going on among the people who are dying,” Arunkumar says. “We have a public health role.”

For example, in 2015, Arunkumar says hospitals were seeing an increase in people who appeared to be overdosing from heroin. Many ended up dying, but autopsies later showed not heroin, but fentanyl, as the cause. All the medical teams needed to do to save people was to increase the dose of Narcan, a medication that quickly reverses opioids’ effects. “Our outside lab told us it was fentanyl, and then we let the ERs know,” Arunkumar says.

The final exam

As the second largest medical examiner’s office in the country (behind Los Angeles), Cook County gets about 25 cases a day and has 23 forensic pathologists, including three trainees, a deputy chief, and a chief. They work in rotation, with five pathologists in the autopsy room on any given day.

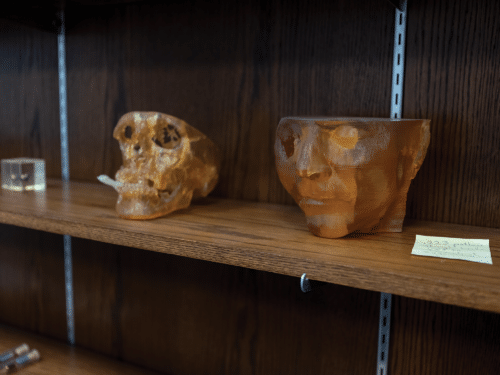

Set up like a large surgical suite divided into two sections, the autopsy room has two doors: One door leads to the hallway and the other to the cooler, with capacity for 275 decedents. Technicians help pathologists with basic processes, while the pathologists study the organs more closely. A large flatscreen monitor on the wall enables the teams to search for projectiles and fractures.

Depending on the case, an autopsy can take anywhere from an hour for a young individual who died from a probable overdose with no foul play, to more than eight hours for gunshot victims with multiple bullet wounds.

“We have to document all the injuries in detail, photograph them. There could be 50 gunshot wounds,” Arunkumar says.

With plastic forceps or gloved hands, the pathologists remove all projectiles in the body to preserve as evidence.

Homicides make up about 15% of the office’s cases. For child trauma incidents, they look at the spinal cord and the delicate nerves within, which can take a painstaking two days.

“You see a lot of different case types, especially in a big office. It is a service to the community, and that’s rewarding.”

Sometimes Arunkumar’s cases hit close to home. She remembers one child who died from thermal injuries; he’d been the same age and stature as her daughter. There was also a physician, who died from stab wounds. Arunkumar thought of her husband, also a physician.

Homicide cases typically go to court two years later. Pathologists take copious notes and photos for trial.

“We teach the jury what happened to the person, explain the injuries. Our job is not to say who did it, but to speak for the patient,” Arunkumar says.

Before the pathologist begins an exam, they receive information about the person’s medical history and the circumstances of their death.

“Were they found in an alley, maybe with a syringe nearby? As they arrive, we photograph and document everything — what they were wearing, how they look,” Arunkumar says.

The team x-rays the body, and then begins the external exam, noting scars, tattoos, injuries, and any disease or trauma. The physician next makes an incision on the chest or abdomen for the internal exam. They remove organs, analyze them, and take samples of blood and urine.

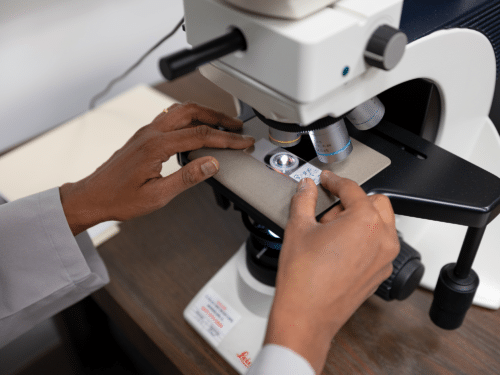

In young adults, they keep the tissues and run toxicology, looking for illicit substances. Next, the physician looks at tissue samples under a microscope. Heart samples, for example, can reveal myocarditis — inflammation of the heart wall, often triggered by a viral infection.

“We see young Black males who suddenly collapsed while playing sports. We’re looking for everything, but often we see an enlarged heart,” Arunkumar says. It’s a genetic disorder called hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Siblings have a 50% chance of having the condition, and Arunkumar takes solace in notifying families of something for which they can test to protect themselves.

Similarly, someone who dies suddenly of a pulmonary embolism may have a genetic blood clotting disorder that they were unaware of. “We’ll let the family know, and they can be tested,”Arunkumar says.

As much as Arunkumar values the work, there’s a shortage of forensic pathologists because people generally go into medicine to heal and help the living. Yet forensic pathologists do help the living, by focusing on the dead: the young person whose family gets closure by finding out a cause of death; the neighbors who evacuate after a couple dies of carbon monoxide poisoning in the apartment next door.

The medical examiner’s office organizes organ and tissue donation, too — another direct way of helping the living, Arunkumar says.

“You see a lot of different case types, especially in a big office. It is a service to the community, and that’s rewarding,” Arunkumar says. “Not many physicians want to do forensic pathology, so that keeps me going. I want more people to be interested in the field.”

Memorializing the dead

Ten miles to the south, primary care physician Adam Cifu, MD, is learning from death, too — but on a smaller scale.

In his early days as an attending primary care physician, Cifu had to make a difficult phone call: to notify a patient’s brother that the patient had died.

After the call, Cifu studied the patient’s face sheet — the summary page with his name, birthdate, health issues, and other notes. This was 1997, before electronic medical records, and clinicians relied on these sheets for a briefing on each patient.

What should he do with the sheet now? Cifu wondered. He didn’t like the idea of crumpling it up and throwing it away. He was the patient’s doctor. That meant something, right?

Instead of the garbage can, Cifu put the sheet in a folder. He added the next sheet to the same folder. And the one after that.

Eventually, with about 10 patients dying each year, the contents required a binder, and then another. For 25 years, Cifu has kept them in his office at the University of Chicago Medicine, where he cares for some 850 patients.

In a 2021 article in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), Cifu wrote about his binder memorials. “It is a place I visit to pay my respects, to learn, to reminisce, and to observe the arc of my career,” Cifu wrote. “Every name is familiar, but there are many about whom I recall nothing else. That evidence of our impermanence saddens me.”

Halfway through the binders, the paper changes from pencil notes on face sheets to the printed font of electronic medical records. He circles the diagnosis on each.

Over time, Cifu has seen the causes of death evolve. In the early years, he says his patients were dying of AIDS, emphysema, and heart disease. The middle years saw more people fall to cancer. Now, Cifu says his patients tend to die of falls or other causes related to old age.

In the JAMA article he further detailed the evolution in causes of death. “This evolution probably reflects improved care of HIV and cardiovascular disease and declining rates of smoking as well as the general ‘aging’ of my patient panel.”

After the piece was published, Cifu heard from other physicians. “OBGYNs famously keep track of all the babies they deliver, but this [collection] seems sort of uncommon,” he says.

The physicians who reached out told him about some of the patients they’d lost. One mentioned that his patients who have died come back to visit unexpectedly and wrote that he wishes he had something like Cifu’s binders “to remind himself more about the person and keep the ghosts at bay.”

Reflection

Yet, even if other doctors don’t keep records in this way, many have their own way of reflecting after a patient dies.

“When we have someone die, we often still round on them. We’ll stop outside the room, pause, and say, ‘Hey, can we revisit this? How is everyone doing with this?’” Cifu says.

He notes that the approach is similar to the timeout that surgical teams take before surgery to make sure they’re operating on the correct patient and performing the right surgery. Only postmortem, the care teams are reflecting on their care and the patient’s experience with death.

Sometimes the person’s absence brings clarity.

“When we figure things out after death, it’s not because there’s an answer. It’s a time when multiple members of the team can sit together in a less stressful way and look at the bigger picture compared to when caring for the patient,” Cifu says.

Every doctor who has worked in a hospital knows the damage physicians can do at the end of life, by trying to prolong it when that may not be the best option, Cifu adds.

“So given our calling to do-no-harm, we really make an effort to not cause those problems. There’s more attention now to living wills, healthcare proxies, and hospice than the generation before me,” Cifu says. “Family used to be around people when they died. People died at home all the time. Then we went through a period where there was less of that, so we’re trying to fight back towards it.”

Over the years, Arunkumar says her work has changed her perspective of life and death.

“You just appreciate the simple things in life. It’s not about the fancy house or fancy car. It’s about your kids, your family, your friends being alive and healthy,” she says.

Like Arunkumar, for Cifu death is not only part of life, but part of work. And with each passing patient, he tries to make sense of it.

“It seems like there’s a whole library of people who have written books about how to die, what to expect at the end. There are those who meet it head on in an accepting way, and those who have all the access to all the resources and fight it to the end,” Cifu says.

Through death and all the trials and errors leading up to it, medicine teaches humility. Cifu sees some patients who he knows won’t make it another year. He acknowledges his lack of power and looks for ways to make that year more pleasant for the person.

“I just wish that people thought about that more. It should be a conversation at the dinner table once a year. If we thought about it more and saw what the end is like, people would make better choices,” Cifu says. “The longer you’ve done it, the more clear that becomes.”