Steve Hamlin works with his personal trainer at rock Steady Boxing. Photo by James Foster

Steve Hamlin’s arms weren’t swinging when he walked, and he was starting to stoop over and shuffle. “I had a lot of discomfort in my back and legs, and I was having a hard time multitasking and remembering what people were saying,” says Hamlin, 61, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in February 2015.

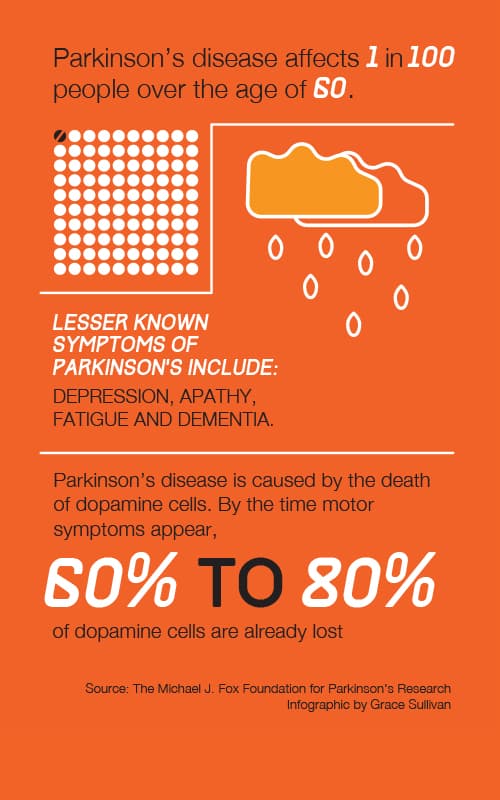

Parkinson’s is a progressive, chronic neurodegenerative movement disorder caused by loss of brain cells that provide dopamine, a neurotransmitter that affects movement. Symptoms might include tremors, muscle rigidity, slowness in movement, difficulty with balance and coordination, and cognitive issues such as dementia and difficulty thinking and understanding.

While there is currently no cure for Parkinson’s—a disease that involves the malfunction and death of brain neurons—advances are improving treatment and quality of life.

Because of his symptoms, Hamlin considered retiring from his job in sales and marketing. But a turning point came when he began treatment at the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago (RIC), where he gained strength—and hope.

Hamlin’s physical therapist, Jillian MacDonald, a member of RIC’s collaborative, multidisciplinary team of specialists in Parkinson’s disease, says therapeutic exercises can help to increase the length of a person’s stride when they’re walking and can improve flexibility, strength, posture and balance as well as reduce the risk of falls. With exercise and the use of strategies taught by a therapist, patients can address episodes of freezing; the sudden inability to move.

Physical therapist Jillian MacDonald (left) works with Barbara Woodbury at the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago. Photo by James Foster

The goal of physical therapy is frequently to get individuals to be more active in their daily life and to exercise more often, MacDonald says, as well as to increase the difficulty of their exercises. “Some patients have smart phones or devices that monitor their activity level. We can use the data collected on these devices to help set activity goals,” she says. “The literature shows that starting to exercise more vigorously early after diagnosis can improve an individual’s function, mobility and quality of life, and it may even delay the progression of motor symptoms.”

After Hamlin completed the physical therapy program at RIC and worked with a personal trainer, he dismissed any thoughts of retirement. “I built up my strength and stamina and flexibility. At work, I am now better at multitasking on conference calls—listening and participating while doing my exercises,” he says. “I’m playing softball and taking boxing lessons for people with Parkinson’s at Rock Steady Boxing.”

What’s more, Hamlin gained a new perspective at RIC. “They changed my frame of mind and helped me understand that Parkinson’s is a journey you take. It’s kind of like the tortoise and the hare [story]. By being diligent and taking a slow, methodical, comprehensive approach, you feel like you have a little bit more control over what’s happening to your body.”

Anne Montana, a speech-language pathologist at RIC, helps people with Parkinson’s who have experienced changes in their voice and speech. They might speak more softly, sometimes in a breathy or hoarse voice, or more rapidly without articulating their words.

“One of the main principles is high-intensity, high-effort exercises,” Montana says. “We work on voice exercises such as having the patient say ‘ahhh’ and sustaining it as long and as loudly as they can [while] we measure their voice on a sound-level meter.”

Montana uses other repetitive muscle strengthening and coordination exercises to help patients who have difficulty swallowing, which can result in choking or food traveling to the lungs and causing aspiration pneumonia, the leading cause of death in Parkinson’s patients.

One Parkinson’s treatment turns to Botox. A serotype of botulinum toxin can be injected into the salivary glands of patients to reduce the production of saliva in order to stop troublesome and embarrassing drooling, says neurologist Michael Rezak, MD, section chief of the Neurosciences Institute of Northwestern Medicine Central DuPage Hospital, medical director of the Parkinson’s Disease Research Society and medical director for the Midwest chapter of the American Parkinson Disease Association. “It’s a quality of life intervention because people can go out again and go to restaurants,” he says.

There has been a change in the use of deep brain stimulation, a common procedure involving a surgically implanted device that electrically stimulates parts of the brain to improve a patient’s motor symptoms. “We’re now implanting the deep brain stimulator earlier to give patients the most benefit before they get to an advanced stage when they start getting motor complications, such as severe dyskinesia, the extra, involuntary movements you see in [actor] Michael J. Fox,” Rezak says.

The FDA recently approved a dopamine replacement medication, in a concentrated gel form called Duopa, for patients in the more advanced stages of the disease. It is administered by a small pump, worn on the patient’s belt or in a fanny pack, through a tube surgically inserted into the small bowel. “You can calculate the precise dose administered in a continuous fashion to get the best therapeutic benefits without the on/off effect or dyskinesias which often occur when you take a pill,” Rezak says.

Vitamin supplements are important, too. Vitamin D3 is crucial for bone health, and evidence shows that low levels may be a risk for dementia. Vitamin B12 deficiency can lead to a number of neurological problems including dementia, neuropathy and spinal cord damage, Rezak says.

Rezak is active in a number of research projects. One involves identifying abnormal proteins and chemicals in the spinal fluid and blood that might predict who will develop Parkinson’s. The disease begins a decade or so before people show motor symptoms, so early screenings can make a big difference.

Some researchers theorize that all neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, are caused by similar changes in brain cells, which suggests that the more we understand about one, the more we’ll understand about the others. “There is a big thrust now to find a vaccine that could lead to a cure,” Rezak says. “I’m very encouraged by the advances we’ve already made in the last 20 years, and we’re moving forward.”