Our writer admits ignorance and investigates to learn more

What do you know about sickle cell disease? Or, what don’t you know? It could be a lot because there are many misconceptions and vagaries surrounding this disease. I certainly didn’t know much when I started researching it.

One commonly made assumption (I made it) is that only black people can have it, but this is untrue. While African Americans can be carriers of the hemoglobin S gene that leads to the blood disease (you have a 1 in 4 chance of being born with it only if both of your parents carry the recessive gene trait), Illinois’ rising Hispanic population is also leading to a spike in the number of people living with the disease statewide.

Sickle sell disease is also present in Africans, Portuguese, Spanish, French Corsicans, Sardinians, Sicilians, mainland Italians, Greeks, Turks, Cypriots, Iranians, Lebanese, Iraqi, Eastern Indians and descendents/immigrants/residents of Southeast Asia.

Since September is Sickle Cell Awareness Month, I thought it best that I learn more about this disease affecting roughly 70,000 Americans. My quest began online at the Sickle Cell Disease Association of Illinois’s (SCDAI) website.

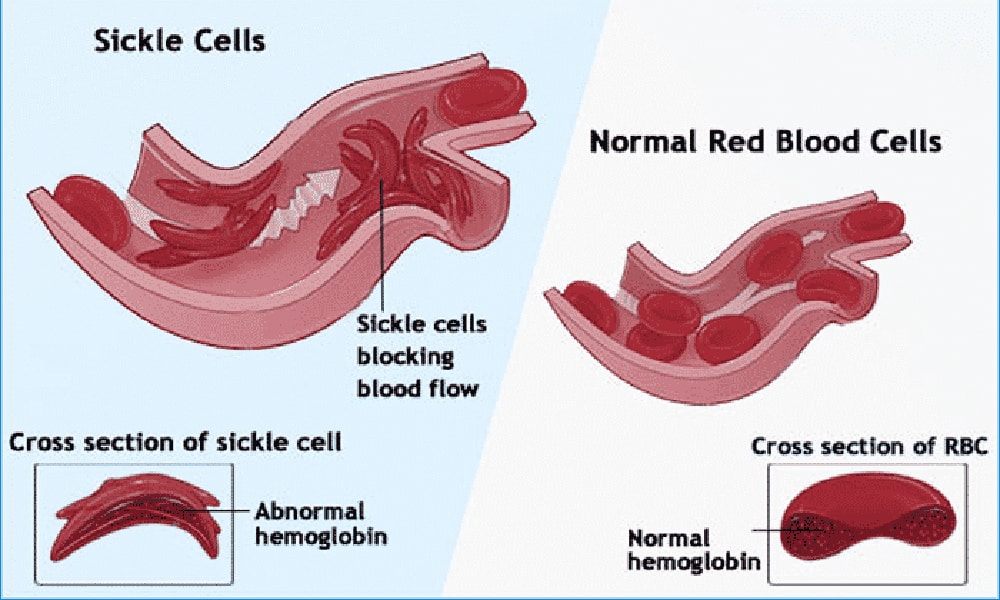

And so, I discovered, that instead of having normal red blood cells that are flexible and globular, people with sickle cell disease have blood cells that are inflexible and sharply pointed at two ends (literally shaped like that farming tool of yore, the sickle). Another way of looking at it is that instead of a red blood cell being shaped like the letter O, it’s shaped like a parenthesis.

These sickle-shaped blood cells are unable to carry as much oxygen to the body’s tissues as are regular blood cells. They also get stuck in blood vessels and break into fragments that interrupt healthy blood flow. This leads to severe symptoms like fatigue, paleness, shortness of breath, small strokes, ulcers on the lower legs and what are known as acute vaso-occlusive episodes (also called crises), to name a few.

I knew that once I hit acute vaso-occlusive episodes, I was in over my head, so I called up Dr. Lewis Hsu, pediatric director of the Sickle Cell Center at University of Illinois Hospital & Health Sciences System, to get an expert’s insight into this disease.

Hsu informed me that acute vaso-occlusive episodes are perhaps the most agonizing symptom of sickle cell disease. “They’re highly unpredictable and vary in length,” said Hsu. “But the pain can be severe—a 10, on a scale of 1 to 10. So for people who have multiple ways of judging pain, some of these episodes are as bad as a broken leg; worse than a gallstone. This lady was describing it to me: ‘It’s like a hot iron sitting on your chest.’”

Acute vaso-occlusive episodes are the primary reasons patients seek medical care in hospital emergency departments. In most cases, a crisis will resolve in 5 to 10 days, although a severe crisis can last months. These episodes are brought on by blood flow problems. A lack or stoppage of blood flow damages or kills body tissue (similar to heart attack or stroke symptoms), which causes intense pain. New research shows that crises can also induce remodeling changes in nerves, so that even after the original tissue damage improves, the affected nerve endings will continue to send out pain signals.

Fortunately, advances in the last ten years have made treatment more effective than ever before. Hydroxyurea is a commonly used and effective medicine that decreases the severity of the disease by lowering the number of pain episodes (including chest pains and trouble breathing) in some patients. In the last ten years, it has begun to be used to treat children and adolescents, in addition to adults. Moreover, Hsu said, “It seems to be improving life expectancy, helping patients retain cognitive function and helping people to go further in school and career because they’re not having so many [unpredictable] absences brought on by the disease.”

Hsu is also optimistic with regard to new medicines coming down the pike. “It’s extremely exciting,” he said. “It’s a whole range of different ways to manage sickle cell, based on newer understandings of how the body is responding. At the University of Illinois, by December, we’ll have six different medicines in clinical trials to offer to people for whom either hydroxyurea is not enough, or [who] don’t qualify for a bone marrow transplant.”

Bone marrow transplants offer the only cure for sickle cell disease. However, in the past, that procedure was met with a high mortality rate among adults and, therefore, was mostly used with children.

“Now, transplant physicians are using more immune modulation,” said Hsu. “They’re tweaking the immune system. They’ll use just enough donor cells so that you can get a cure of the disease without causing too much damage to the body or having low survival [rates].”

Although affordability and health-related complications limit the availability of transplants to those who need them, progress is being made. At the time of the interview, Hsu reported that two Chicago adults who had undergone the transplant were doing well.

Along with burgeoning treatment options and an updated methodology for bone marrow transplants, I asked the doctor what he thought the next step was in curing sickle cell disease. The solution, he said, was threefold:

1. Generating public awareness is important, “so that we don’t have to go and explain what sickle cell is. And so that people who have the sickle trait will understand what this is, know what genes they are carrying and that they might have children with sickle cell disease.”

2. Setting the bar for better treatment standards is also a must. “Right now there are patients who roam around floating from one emergency room to another without being plugged in for preventative services or having hydroxyurea explained to them or being made available to them. So many people are getting way substandard care without understanding that it’s substandard.”

3. Ensuring access to care is the final step. “The idea that this is an inherited, pre-existing condition is something that is addressed in health care reform (The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act). So now, people can still get insurance even though they have this genetic condition. But if some of that gets repealed, then, you know, these kids who have these inherited conditions will be out of luck or have sky-high insurance rates.”

If you’d like to learn more about sickle cell disease and what you can do to help further research and awareness, please check out the Sickle Cell Disease Association of Illinois at www.scdai.org.