Photos courtesy of Rush University Medical Center

With a fever, a cough and trouble breathing, Chicago resident Deborah Lielasus, who lives in North Center, was worried that she had COVID-19. Because she is 60 years old and immunocompromised due to autoimmune myelitis — both coronavirus risk factors — she was extra-concerned. She feared that her condition could get worse, especially with her trouble breathing.

Lielasus first called her primary care physician at Northwestern Medicine. A nurse referred her to the hospital’s COVID-19 nurse line, so Lielasus stayed on the phone, detailing her symptoms and her risk factors. The nurse on the COVID-19 line told her to go to a pharmacy and get a mask or go to an emergency room. But Lielasus knew that going to an ER meant exposing other people to the virus, if she had it.

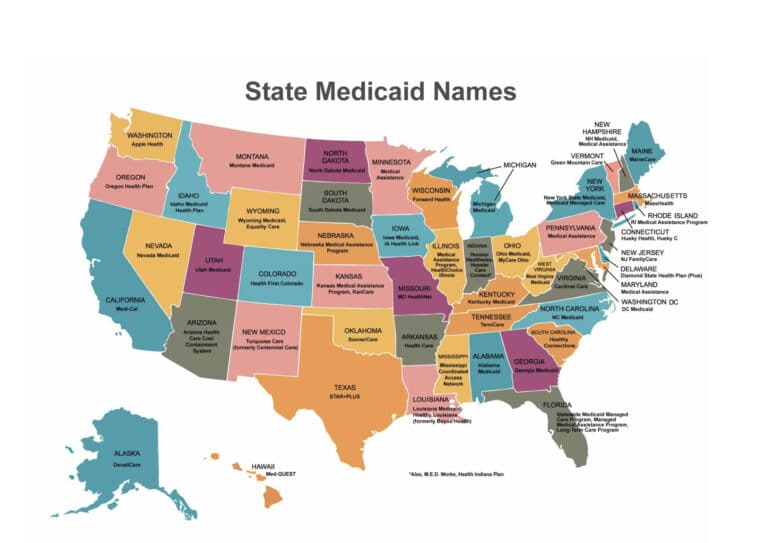

So she called her doctor’s office again. The nurse told her that the hospital didn’t have any tests and recommended Lielasus try the Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH), which — along with other state, county and city health departments — has been acting as gatekeeper for the tests.

When doctors want to order a coronavirus test for a patient, they first have to call a health department to get the test — which is not how other testing, like for flu or pneumonia, works. Private laboratories and hospitals are working rapidly to develop their own tests; however, when Lielasus was calling, none were yet available.

Lielasus called CDPH and got disconnected, leaving her in limbo.

“How can you contain and manage [COVID-19] without knowing who has it?” she asks. “The overriding feeling I have is that it’s no longer my doctors’ and medical facilities’ concern whether I die or not. Their concern is following protocol and doing what they’re told to do.”

“I’m 60 years old. I’m definitely sick. I hope I don’t die tomorrow,” she says.

Shortage of testing

A Chicago-area emergency room medical director and physician (who requested his name remain private) expresses similar frustrations and uncertainties. He says the Illinois Department of Public Health (IDPH) has repeatedly denied him COVID-19 tests for patients.

Before he can run a COVID-19 test, the doctor says, IDPH says he has to test for flu and other viral respiratory infections, which can take seven to 10 days for results. Meanwhile, healthcare providers and anyone the patient is in contact with are potentially exposed to the coronavirus.

“It’s a farce. I’m telling you firsthand that the public health departments are making up reasons to not test patients,” the medical director says. “Same thing in New York City — an Uber driver went to the ER three times before they would agree to test him. He came back positive, after exposing dozens of hospital staff and Uber passengers.”

The lack of tests led one infectious disease expert in Seattle, Helen Chu, MD, MPH, to bypass the federal government and begin performing tests at the University of Washington without government approval. Those tests revealed that COVID-19 had been spreading undetected throughout the area, resulting in at least 37 deaths by mid-March.

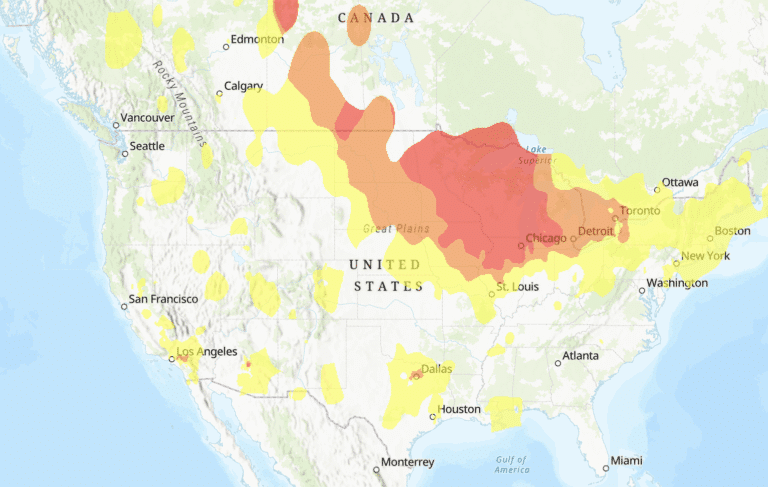

The U.S. is at a crucial juncture right now. The more people who choose to self-quarantine — watching Netflix over going to the theater, staying home with their children instead of having play dates — the less opportunity the virus has to spread. It’s a well-documented approach — Public Health 101.

But without the test numbers to show how many people are actually infected with the coronavirus, the general public risks not taking self-quarantine or physical distancing seriously, and more vulnerable people are being exposed.

“I cannot emphasize that at this moment in human history,” Ehrman says, “social distancing, social isolation (voluntary for now) and widespread testing in the U.S. are the most important things we can do.”

Increased testing will show where COVID-19 currently is and isn’t, enabling medical and public health efforts to focus resources on places most in need. It also will slow the number of infections and keep the healthcare system from becoming overloaded by people needing intensive care.

“The reason South Korea has a low fatality rate is because they’re testing everybody who wants to be tested. There are drive-through places where you roll down the window and get tested,” says Howard Ehrman, MD, MPH, a former CDPH assistant commissioner, currently an assistant professor at the University of Illinois-Chicago. Still, drive-through testing isn’t a fix-all, he notes, as many families in Chicago don’t have a car, which makes drive-through testing unavailable to them.

Widespread testing is key, Ehrman says. South Korea used the World Health Organization’s (WHO) test early on and has tested as many people as possible. In contrast, the CDC has limited testing and tried to develop its own test instead of using the WHO test.

Ehrman, who served as Will County’s chief medical officer during the ebola epidemic, explains how he would handle the situation in hospitals, beginning with a rapid influenza test (which not all hospitals carry). “I’d do that test and, if negative, go right to the COVID-19 test. Patients get lost otherwise.”

This battle for testing begs the question — how prepared are hospitals?

Evolving by the hour

That preparation is a work-in-progress. Hospital staff members meet and train multiple times a day. Staff who work directly with patients get daily temperature checks. But hospitals are working with federal and local updates that change by the hour—and they have to adjust rapidly in response.

Advocate Good Shepherd Hospital in Barrington started drive-through coronavirus testing — in which people undergo a nasal swab test without leaving their cars — and Advocate Hospitals announced they won’t be charging patients for coronavirus testing or treatment.

NorthShore University HealthSystem has developed its own COVID-19 test. However, because testing capacity is still limited, the system can only test people who meet criteria from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Rush University Medical Center has set up a tent triage in its ambulance bay to assess symptomatic patients without putting other ER visitors and staff at risk of exposure. Rush’s main butterfly-shaped building was designed to flex, grow and isolate in case of this very scenario — a viral pandemic. When the team began planning the new building in 2006, five years after the Sept. 11 attacks, bioterrorism was a primary focus.

“The shape is about how we wanted the inside to function — form following function,” says Tony Perry, MD, vice president of ambulatory transformation at Rush.

Each wing of the building can be isolated, creating units that don’t recirculate air into the rest of the hospital. The ER has hidden walls, enabling it to double the number of patients it can hold. The staff can create pop-up isolation rooms in the ER lobby, suctioning air out of the room while also providing fresh oxygen within the room. This protects the rest of the hospital from exposure and is used for specific types of contagious illnesses, like tuberculosis.

Perry and two other physicians worked closely with design and infection control teams in developing the building. And they were working from scratch. Despite traveling to hospitals across the country, they found no other hospital in the U.S. had created an entire facility with a primary focus on preparedness, Perry says. “The fact that we did it has been a quiet topic, because we haven’t needed it.”

Perry pauses and adds, “This is fascinating but frightening at the same time. It’s amazing to see all of this stuff that was a framework and strategy for preparedness [come to life]. But at the same time, I hate to see it go into use.”

To slow the spread of the virus, Rush is offering on-demand video visits to keep people who could be contagious in their homes, instead of in a waiting room with other people.

“We can give some guidance. Either they don’t need to be worried, or [we tell them] what the right next steps are,” Perry says. “We have the ability to get good info in people’s hands. The more proactive we can be, the more we can blunt the impact of the spread in our communities. You can see people emotionally de-escalate.”

That communication is key — and the general lack of it from federal officials is where so much panic and uncertainty is breeding right now.

Ehrman says, “There should be a public service announcement every hour on every radio and TV station in English, Spanish, Polish,” educating people on protective measures and social distancing.

Hospitals have been sending out regular updates, keeping employees and nurses informed, says Alice Johnson, executive director of the Illinois Nurses Association. However, she adds, “One thing that we’re hearing consistently is a concern about lack of tests and ineffectiveness of education that’s been provided to general public.”

Johnson mentions one nurse who saw a patient “wearing multiple masks, which is ineffective at preventing the virus. We need more public education about what steps need to be taken.”

She adds that nurses’ concerns are growing — from a lack of protective equipment such as masks to employees needing to use benefit time to cover sick leave related to the virus. “In addition, with the closure of the schools happening in Illinois, nurses need assistance with childcare while they are on the job and their children are not in school,” she says.

Still, Chicago-area hospitals are fighting to stay ahead of the surge of COVID-19 cases, and healthcare providers are trying to keep up with the influx of concerned patients.

Last week, Lielasus was one of those patients. After sharing her symptoms and medical history with a clinician over Rush’s video visit platform, the nurse practitioner told Lielasus she didn’t meet the CDC’s qualifications for coronavirus testing, because she had not traveled to an affected country or had direct contact with a known person with COVID-19.

But 30 minutes later, Lielasus received an update: She suddenly qualified for testing under the CDC’s new protocol that states clinicians can test “symptomatic individuals such as older adults and individuals with chronic medical conditions and/or an immunocompromised state.”

Twelve hours after first attempting to get tested, Lielasus says, “The protocol changed in a heartbeat.” Lielasus says she can’t help but feel abandoned by the health system because no one seems to know what to do.

Lielasus went in for her test on March 14, and as of this writing is still awaiting results. “I was told 48 hours, four days, and we don’t know,” she says, of when she might receive results. “My husband and I are hunkered down.”

Meanwhile, Ehrman, who survived polio paralysis as a kindergartner, sees so much potential in Chicago’s power to manage this pandemic locally. From hospitals and medical schools ranked among the best in the country to giant laboratories, the medical community needs to take the lead if no one else will.

“I cannot emphasize that at this moment in human history,” Ehrman says, “social distancing, social isolation (voluntary for now) and widespread testing in the U.S. are the most important things we can do.”

An award-winning journalist, Katie has written for Chicago Health since 2016 and currently serves as Editor-in-Chief.