Who’s at risk when poor air quality spikes, and what can people do to protect their air?

Chicagoans who gazed out their windows on a day in late June discovered an orange haze blurring their view. When they opened their front doors, the smell of smoke enveloped them. And as dusk approached, many marveled at the beauty of the vivid red setting sun — even if they simultaneously worried about all that smoke in the air.

These intriguing phenomenon on June 27 all had the same origin: smoke drifting into the city from hundreds of wildfires burning throughout Canada. By noon on June 27, Chicago’s air quality index hit 209, classified as “very unhealthy” by the Environmental Protection Agency, and giving the city the dubious distinction of attaining the worst reading for any major city worldwide, according to IQAir, a Swiss company that measures air pollution concentrations around the globe.

Many people in the Chicago area reported temporary symptoms, such as burning eyes, congestion, and headaches. Sean Forsythe, MD, director of the division of pulmonary and critical care at Loyola University Medical Center, says, “On a short-term basis, the bigger particles can irritate the breathing tubes of healthy people, causing congestion, throat irritation, coughing, sneezing, tiredness, headaches, and the inability to exercise as much as they would on a day when the air quality is good.”

Ongoing exposure to air pollution comes with more serious risks. It’s associated with cellular inflammation and an imbalance of antioxidants and free radicals in humans, which creates an ideal environment for cancer and many chronic diseases. These diseases include heart disease; lung diseases; diabetes; obesity; and reproductive, neurological, and immune system disorders. The World Health Organization (WHO) classified air pollution as a human carcinogen in 2013.

Air quality risks

Even without wildfire smoke, Chicago’s air quality needs improvement, according to a 2023 American Lung Association study that looked at air quality nationwide from 2019 to 2021. Chicago ranked as the 17th most polluted city for ozone, with Cook County and surrounding counties receiving a failing grade.

The wildfire smoke permeating the air has more serious repercussions for people with respiratory diseases such as asthma, chronic bronchitis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). In fact, on that smoky day in June, Forsythe’s asthma patients were the canary in the coal mine. Forsythe says some called him because of the poor air quality before he even heard about it because it was triggering an increase in their symptoms. In addition, Forsythe says, “The small particles can travel deep into the lungs and cause inflammation that impairs the body’s ability to eliminate some infections. Some studies have shown there is a correlation between long-term exposure to heavy wildfire smoke and heart attacks and strokes.”

Exposure to wildfire smoke can also have a negative impact on the health of two specific age groups: young children and older adults because their immune systems don’t work as well to eliminate the particles, Forsythe says.

One study also found that fine particles in the air were linked to a greater risk of developing Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and other dementias.

Pregnant people are also vulnerable to the harmful effects of wildfire smoke. Melissa Simon, MD, obstetrician/gynecologist at Northwestern Medicine, says that as the fetus grows and takes up more space, the pregnant person’s lung capacity decreases. This makes breathing difficult and the pregnant person more vulnerable to lung infections.

When a pregnant person has difficulty breathing, the fetus may not receive enough oxygen. Simon says this could hamper the overall well-being of the fetus, and the baby might be born early or have a low birth weight. However, she adds, it’s difficult to draw conclusions like this because researchers have done very few studies on the effect of air pollution on pregnant women.

A heavy burden for some

People who live in communities with heavy traffic or industry may experience even worse health symptoms related to wildfire smoke because the smoke is adding to heavy loads of air pollution already present in certain Chicago communities — primarily Black and Brown neighborhoods such as Little Village, Austin, and Lawndale. “Due to structural racism and the design of the neighborhoods where they live, they will be exposed to pollution from industry and traffic on highways and expressways,” Simon says.

Two days after Chicago’s air quality index broke 200, Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson announced Chicago’s cumulative impact assessment, which the Chicago Department of Public Health and the Office of Climate and Environmental Equity are conducting to assess how pollution, social factors, and health issues impact the city’s residents.

While Chicago can make changes based on these findings, nothing can prevent the harmful smoke from wildfires, which have increased in intensity, size, and duration due to climate change.

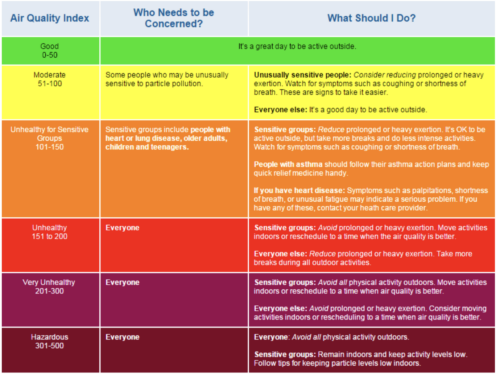

Forsythe recommends that everyone follow his patients’ example and regularly check their local air quality. Use your phone’s weather app or type your zip code into AirNow.gov.

If the air quality is unhealthy, Forsythe says people should stay indoors. If they have to venture out, in spite of mask fatigue due to Covid-19, he recommends wearing an N95 mask, not a cloth or surgical one, because it is the best protection against harmful air.

Nancy Maes, who studied and worked in France for 10 years, writes about health, cultural events, food and the healing power of the arts.