Where flooding and sewage treatment meet — and how both impact people’s health

Flush your toilet or rinse your kitchen sink, and you probably don’t spend a ton of time thinking about where that water goes next. Yet, wastewater treatment ranks as one of the most vital public health innovations in human history, due to the advances it has allowed societies to make in establishing cities, economies, and the arts.

“As a public health agency, we prioritize and center the health of the region, the state, and the country,” says Metropolitan Water Reclamation District (MWRD) Commissioner Eira Corral Sepúlveda. “If we don’t do our job right, there are consequences down to the Gulf of Mexico. There’s a global impact.”

But in Chicago — as thousands whose homes have flooded recently know — wastewater and storm water go together in this city. Sewage water and storm-water drain into the same pipes, instead of separate pipes. This type of sewer system is a leftover from the U.S.’s early infrastructure. Today about 772 communities nationwide, serving 40 million people, have combined sewer systems.

When heavy rain storms hit, combined systems risk overflowing large amounts of sewage water into local waterways — a Clean Water Act violation. In 2011, Chicago signed a settlement with the Environmental Protection Agency to reduce the number of overflows through upgrading infrastructure — a massive project the MWRD had been working on since the 1970s.

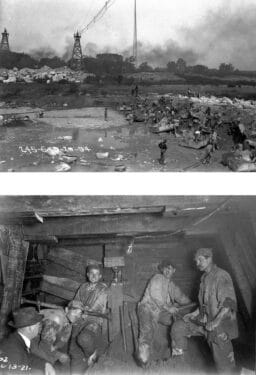

the MWRD’s downtown office. Photo by Katie Scarlett Brandt

People rarely think about any of this until something goes awry.

Christian Langill remembers the call. It came on a Sunday in September, as the sky outside of his church filled with dark clouds, and relentless rain pooled in the streets and sidewalks.

Langill’s teenage son, meanwhile, was alone at the family’s Portage Park home. When Langill answered his ringing phone, he heard the fear in his son’s voice, reporting that their basement was filling with water, coming up from the floor drains.

“He was pretty scared,” Langill says. “I was too. I walked him through turning off the electric, getting stuff off the ground. He could’ve gotten electrocuted.”

That September 2022 storm dumped as much as 4.25 inches of water on parts of Chicago, resulting in a storm so powerful that it has a 1% chance of happening in any given year.

“Now these 100-year storms show up every three years,” says Dan Lyvers, chief operating engineer at the MWRD plant in Stickney. “Last September, we got an entire month’s worth of rain in four hours.”

Health risks

During the September 2022 storm, the city’s sewers struggled to keep up with the deluge, and streets and homes flooded with a mix of wastewater and storm flow. Nearly a foot of murky water submerged the Langills’ basement. In 14 years in the house, they’d never seen anything remotely like it.

The basement filled again 10 months later when a massive storm system tore through Chicago in July 2023, shutting down I-55 and I-290, stranding cars under viaducts, and delaying the NASCAR street race downtown. The storm even caused audio engineer Duane Tabinski’s tragic death by electrocution while setting up the event.

“He was a professional. If that happened to him in that NASCAR situation, what can happen to someone in their home?” Langill says. “How many people affected times how many homes?”

Electrocution isn’t the only risk to human health. Flooded homes leave behind moisture, enabling mold, which can cause asthma attacks; eye, skin, throat, and lung irritations; and breathing difficulties and infections. And with Chicago’s combined sewer system, people risk exposure to sewage-tainted water.

“Now these 100-year storms show up every three years,… Last September, we got an entire month’s worth of rain in four hours.”

Drowning is a serious risk with heavy storms, too. Children playing near flood water have drowned, and cars have been swept away in as little as 12 inches of moving water.

Flood victims’ mental health also takes a hit, according to a 2020 study in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. Researchers reported that people who had been through floods were as much as nine times more likely than the general public to experience mental health problems — primarily post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as well as depression and anxiety.

Lee Langill, Christian’s wife, pays close attention to rain forecasts now. “I would say when there’s a forecast of storms, I feel overwhelmed really. We’ve got to prepare, have to make sure things aren’t on the ground. You’re just in this heightened state of anxiety.”

The MWRD, demystified

The MWRD manages and cleans that storm water. But their work goes beyond storms. Chicago created the MWRD in 1889 to take on an engineering feat: reversing the Chicago River’s natural flow away from Lake Michigan. This was an attempt to keep wastewater out of drinking water, and it involved digging a 28-mile canal, called the Sanitary and Ship Canal.

Since the 19th century, the MWRD has grownto 61 miles of canals, seven water reclamation plants (which clean wastewater), 110 miles of deep tunnels, and hundreds of miles of sewers throughout Cook County.

Today’s MWRD treats more than 1 billion gallons of water daily, serving nearly 13 million people in Chicago and 128 Cook County municipalities. The $1.2 billion agency is also a major employer: 2,000 people work there, including engineers, mechanics, and microbiologists. With 24,000 acres in Cook, Will, DuPage, and Fulton counties, the agency leases land to businesses that rely on water access, such as oil refineries, asphalt plants, and manufacturers.

Still, the MWRD is one of the most approachable local government agencies, hosting outreach events, offering plant tours, and partnering with local environmental organizations.

“The MWRD has become a really forward-thinking agency,” says Margaret Frisbie, executive director of Friends of the Chicago River, a nonprofit that improves and protects the Chicago-Calumet River system. “Having access to a government agency that’s willing to partner with people, listen to people — when we partner together, we really can affect change.”

However, Frisbie adds, it’s key that people pay attention to how Chicago’s water system works and what the agency does. Cook County residents typically interact with the MWRD every two years, when they vote for the commissioners who oversee the agency’s work.

“Every one of us — whether using pesticides, leaking car oil, or putting pharmaceuticals down the drain — we’re all contributing to what’s in our waterways. It’s important to know that you have an impact, and these elected officials have an effect,” Frisbie says.

As one of nine elected officials, Sepúlveda joined the MWRD in 2020. Her daily calendar quickly filled with back-to-back meetings. One of those recent meetings was about a potential career pipeline program with Wilbur Wright College, a city college on Chicago’s Northwest side. Sepúlveda says she sees such partnerships as a way to increase diversity in the agency while benefiting individual students. “There’s a great opportunity to get the younger generation involved and engaged, and to channel that anxiety around climate.”

After all, she adds, “This organization is at the heart of so many important issues: workforce, equity, climate change, infrastructure, public health.”

Monitoring the gauges

As the Langills’ basement flooded this past July, 10 miles away two MWRD waterways dispatchers closely studied reports playing out on a ring of giant monitors. They were stationed in a windowless control room at the MWRD’s main offices at 100 E. Erie Street. One screen showed the radar and forecast, another rain gauges, and another waterway elevations.

A dispatcher staffs this control room 24/7, managing the intertwined Lake Michigan, Chicago and Calumet Rivers, North Shore Channel, and more. There’s so much water to manage because before Chicago became a major metropolis, the area was marshland. The waterways motivated settlers to build here.

But now, Chicagoans are increasingly feeling the downside of all that water. Halle Morrison, assistant professor of chemistry, physics, and geology at Malcolm X College in Chicago, says that in the northern tier of North America, one of the most visible ways people experience climate change is through flooding. Increased CO2 emissions from human activities such as industrial processes are “creating a blanket over the world.” Morrison says.

“Every one of us — whether using pesticides, leaking car oil, or putting pharmaceuticals down the drain — we’re all contributing to what’s in our waterways.”

Having some CO2 in the atmosphere is normal. It keeps our living area warm and protects us from the cold of outer space. But billions of humans’ activities are creating an excess of CO2, “which makes the ‘blanket’ thicker and better able to hold in heat,” Morrison says. “For North America, it’s only 1-2 degrees Fahrenheit, but that’s what’s causing the crazy weather events. It’s invigorating the hydrologic cycle: the evaporation of water, the transport of water, and the falling of water.”

During particularly bad storms, two MWRD dispatchers monitor the readings in the downtown control room. They consult with meteorologists, who speak in probabilities and percentages, and make decisions on when to close the gates at the lakefront to reverse the Chicago River’s flow back into Lake Michigan — something they can only do when the river’s level surpasses the lake’s level.

“There is NO MAGIC KEY OR BUTTON to use at will,” the MWRD wrote in a press release following the July 2 flooding, when rainfall totals ranged from three to eight inches. “If we were to open the lock and gates too early, Lake Michigan would have a tsunami effect, overtaking the river and flooding everything in its path in downtown Chicago and along the waterways, totally decimating the riverwalk and municipalities downstream, on the South Side and on the North Side. The destruction that would be caused by opening the gates and lock too early is unimaginable.”

Filling the reservoirs

The city’s combined sewer system filled quickly during the downpour, flowing into the MWRD’s intercepting sewers. Once the sewers reached capacity, the water then dove down a shaft that travels 350 feet below ground, to the deep tunnel system, which moved it to the reservoirs.

The MWRD’s deep tunnel and reservoir system ranks among the largest civil engineering projects on earth, capable of holding 17.5 billion gallons of water — 2.3 billion in the 110 miles of tunnels and 15.15 billion in the three reservoirs. The system saves more than $180 million in annual flood damage, according to MWRD estimates.

Of the agency’s three reservoirs, the two-phase McCook Reservoir in Bedford Park is by far the largest. Phase 1 began operation in 2017 and holds 3.5 billion gallons of water. Phase 2 will open in 2029, holding an additional 6.5 billion gallons. The reservoir is so massive, it makes the excavators and dump trucks working within it look like play toys.

Despite the reservoir’s gigantic size, when MWRD planners envisioned it, climate change didn’t factor in. “This was planned in the 1970s, with data from the ’50s and ’60s. Rainfall patterns have gotten higher,” says Kevin Fitzpatrick, assistant director of engineering at the MWRD.

As a storm rages, the McCook reservoir begins to fill with water from the deep tunnel system.

If the reservoir reaches capacity, the Racine Avenue Pumping Station eight miles away could pump the water into the south branch of the Chicago River, also known as Bubbly Creek. The MWRD avoided pumping into the river in all of 2022. Prior to the deep tunnel and reservoir system, they would pump water into the river as frequently as 10 times a year.

Since 2017, Fitzpatrick adds, McCook Reservoir alone has kept 100 billion gallons of waste and stormwater out of the Chicago River.

Cleaning the water

Meanwhile, as the reservoir fills, engineers and operations personnel at the seven treatment plants hunker down to manage the waste and stormwater flow from the sewers. The entire process from dirty to clean water takes 12 hours.

The water first goes through coarse bar screens, which collect large debris such as sticks and flushable wipes. Next, the water travels up to ground level, into aerated grit tanks and settling tanks, where solids drop to the bottom. A drain then funnels the solids away for treatment. The water goes to tanks full of microbes that consume the remaining solids. Once cleaned, the water is released to the waterways.

On a recent public tour of the plant, Commissioner Sepúlveda joked with one of the attendees, age 4, who was upset to be at the MWRD rather than the zoo. Sepúlveda intervened with a story of the tiny microbes at work in the tanks.

“I told him how they have to be not too hot or toocold, and how if they’re the wrong temperature, they’ll get grumpy and not do their job,” Sepúlveda says.

What remains of the solids — called sludge — goes to underground digesters with microbes that further break it down and reduce odors. A machine then spins the sludge to dry it, and the sludge travels by train to long rows of beds, where the solids sit before moving on to their next phase: fertilizer.

Some of those sludge beds, at the Calumet Water Reclamation Plant, sit on MWRD land near Altgeld Gardens. At this sprawling Chicago Housing Authority development on the far South Side, the air frequently smells putrid — especially on muggy days.

Cheryl Johnson’s family moved to Altgeld Gardens — originally built as homes for Black veterans and war industry workers after World War II — in 1962, when she was 1 year old.

“Flooding is a major issue. If it rains an inch, we flood,” Johnson says.

The reason is two-fold, because of the land’s proximity to the Little Calumet River, and because of the land’s historical usage, with large swathes taken for illegal landfilling that further destabilized it.

The new environmental justice

Morrison, the Malcolm X professor, says flooding is happening most in vulnerable and underserved communities.

“Flooding may be the new environmental justice movement because more disadvantaged communities are exposed to flooding problems. It’s a whole new issue that we’re going to have to deal with now that climate change is here,” she says.

Yet, flooding isn’t Johnson’s only worry. She’s concerned about potential air pollutants from the sludge at the MWRD facility. The smell, she says, is unbearable.

Johnson leads the environmental organization People for Community Recovery (PCR), which her mother, Hazel M. Johnson, started in 1979. Hazel’s husband and several of their neighbors were dying of cancer. Her anger and grief propelled her into researching the area’s heavy load of waste and industrial sites. Today, Cheryl Johnson leads a bus tour telling stories of the area’s toxic history.

One of the final tour stops takes attendees down Hazel Johnson EJ Way, which the state dedicated in 2016. The memorial runs down a tree-lined stretch of 130th Street, near the Bishop Ford Freeway — directly past the MWRD’s sludge beds, which Cheryl Johnson has watched expand throughout her life.

MWRD Commissioner Sepúlveda acknowledges Chicago’s history of racial inequities and disinvestment. “When we’re pushing for green and gray infrastructure, we’re pushing to keep equity in mind, so the communities that have suffered from disinvestment benefit,” she says.

One of the ways the MWRD does that is through the Space to Grow partnership. In April 2023, Chicago Public Schools, the Chicago Department of Water Management, and the MWRD announced a $52 million investment over the next four years to make school play yards better able to absorb rain water through native plants, rain gardens, and permeable play surfaces. The program started in 2014 through Openlands and Healthy Schools, with 34 of 658 CPS schoolyards renovated so far.

“This uplifts the experience for the neighborhood and the students in that school, but it also alleviates flooding in the area,” Sepúlveda says.

Frisbie, of Friends of the Chicago River, sees clear value in such investments. “For a long time, there was a belief that gray infrastructure is the only choice we have, but now with an agency as powerful in the world as MWRD, they can really set the bar higher for everybody else.”

Back in Portage Park, Christian and Lee Langill continue to battle the realities of their flooded basement. They’ve vacillated between attempting to fix the issue and waiting for the next storm. They’ve joined a toxic mold resource group on Facebook and talked with other Portage Park residents who have spent thousands on valve systems for their homes, with mixed results.

They’re also waiting to see if any other options become available, as federal disaster officials survey Chicago home and business owners about their flooding experiences in July and FEMA announces financial assistance for qualifying flood victims. Flooding damaged roughly 18,000 homes that day — a preliminary estimate based on 311 calls and other data.

“You’re talking about at least $10,000,” Lee says, “and it can’t guarantee that you’re not going to have the same problem again. We have a son in college; we can’t afford to spend money on a potential solution that might not work.”

In the meantime, the Langills watch the weather. And there’s no end in sight.

Photos by Jim Vondruska

Originally published in the Fall/Winter 2023 print issue.

An award-winning journalist, Katie has written for Chicago Health since 2016 and currently serves as Editor-in-Chief.