Chicago explores the role of trees in human health and heat mitigation

This is not a joke. Ready?

What mitigates major chronic diseases, all while cleaning and cooling the air, decreasing stress, and beautifying neighborhoods?

Trees.

“If trees were a vitamin, everyone would be lining up to take it. The benefits are enormous,” says Raed Mansour, director of the office of innovation at the Chicago Department of Public Health.

Marc Berman, associate professor of psychology and director of the Environmental Neuroscience Laboratory at the University of Chicago, says that because humans are part of nature, “nature is a necessity, not an amenity. It’s a must. We can’t have neighborhoods that don’t have nature.”

According to Berman’s studies, published in Psychological Science and other journals, humans gain psychological, cognitive, and physical health benefits from nature, as well as improved working memory and a propensity to think less about oneself and more about others. One of Berman’s studies found that if there are more trees in your neighborhood, there is less cardiovascular disease.

“Having just 11 more trees on a city block decreases cardiovascular conditions in ways that are comparable to increases in annual personal income of $20,000, moving to a neighborhood with a $20,000 higher median income, or being 1.4 years younger,” Mansour says.

Trees impact human health in many ways beyond releasing more oxygen into the air. Whether they realize it or not, people respond naturally to nature’s colors, curves, textures, and patterns.

Leaves’ green hues, for example, create a soothing response in our brain, says Navraaz Basati, a horticultural therapist and certified nature and forest therapy guide. Nature’s scents can slow our breath, boost our immune system, and invigorate us, she adds. And because of the many nerve receptors in our hands and feet, touching nature has an uplifting influence on our organs and cognitive functioning.

Trees prevent flooding, too — an increasingly common issue in the Great Lakes region. According to the Morton Arboretum’s 2020 Tree Census Report, trees in Chicago and its surrounding counties annually intercept 1.5 billion cubic feet of water, saving $100 million in stormwater damages and treatment.

They have other infrastructure benefits, too. They store millions of tons of carbon, filtering pollutants from the air. And the shade that trees provide saves residents $32 million dollars on cooling costs annually.

Canopy coverage

The report also finds that the city’s average canopy coverage — the leaves, branches and stems that shelter the ground when viewed from above — is only 16%. This percentage is below the ideal average for cities, and it’s even lower in historically under-resourced and underserved communities, according to the Chicago Region Trees Initiative.

The city’s canopy dropped 3% during the past decade, reports nonprofit environmental organization Openlands, while six of the seven neighboring counties saw canopy growth.

According to the 2020 tree census, a significant part of this loss was due to the emerald ash borer’s decimation of the city’s ash trees, which used to be the main tree lining many of Chicago’s streets.

“Scientists actually have been able to track an increased association with cardiovascular and respiratory illness and death, as well as an increase in violent crimes and property crimes, in the neighborhoods that lost these [ash] trees,” says Jessica Turner-Skoff, PhD, The Morton Arboretum’s first Science Communication Leader.

Another Chicago study looked at parks with either no trees, small trees, or really big trees. The researchers found that people more frequently visited parks with big trees, spent longer periods of time in them, and the parks attracted a wider age of children.

Turner-Skoff says that parks with big trees create greater social cohesion and community ties, potentially reducing loneliness. U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, MD, declared loneliness as “an underappreciated public health crisis that has harmed individual and societal health.”

Taking care of the air

“The leaves are the tree’s powerhouse,” Mansour says. Leaves along with branches help mitigate pollution — a major contributor to environmental and racial injustice in Chicago, as well as a direct cause of multiple health issues, from respiratory conditions to cancer.

“Pollution is linked to everything, including increased blood pressure, respiratory disease, and cardiovascular problems,” Turner-Skoff says. Trees act as scrubbers, cleaning the air by trapping pollution on their leaves and branches, as well as reducing the negative effects of carbon dioxide (CO2) in our environment. Scientists have linked extreme weather, food supply disruption, and increased wildfires with elevated levels of CO2.

In communities such as Little Village (or La Villita), located on Chicago’s Southwest side, air pollution has been a long-time health and environmental menace. According to the Illinois Environmental Council, the area has served as an industrial corridor since the 1920s, with contributors to the degraded air quality such as the developer Hilco and the now-defunct Crawford Coal Plant.

When the Crawford Coal Plant was shut down in 2012, the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization and community partners proposed to replace it with a solar farm or commercial kitchen, with no success. In 2018, Hilco purchased the site to build a one million square-foot Target warehouse, according to the Illinois Environmental Council.

On the morning of April 11, 2020 — in the middle of a respiratory pandemic — Hilco used explosives to demolish the old Crawford Plant smokestack without proper dust mitigation or warning.

As a massive cloud of dirt, asbestos dust, and smoke overtook Little Village, it became immediately clear that the implosion was botched. Lethal particles filled the air in a neighborhood with “already degraded air quality and disproportionate asthma rates while a pandemic that attacks respiratory systems raged,” the Illinois Environmental Council reported.

The compensation? A lawsuit by the state of Illinois against Hilco and its general contractors MCM Management Corp. and Controlled Demolition Inc., resulted in a settlement of $370,000, which was given to Access Community Health Network in Little Village.

Dulce Maria Garduño Maya, a resident of neighboring Pilsen, has been walking Little Village since 2022 on behalf of the Chicago Department of Public Health, educating neighbors about how trees mitigate pollution from the diesel trucks delivering to the Target Warehouse at 3501 S. Pulaski.

She helps community members realize that although they feel healthy, others in the community have compromised immune systems or breathing issues. And, the effects of the area’s pollution can show up later in life, she warns.

Garduño Maya is part of the Community Tree Ambassador program. Chicago launched the program in May 2022 as part of Our Roots Chicago, the city’s commitment to environmental justice and equity and the 2022 Climate Action Plan. In 2022, the city trained 60 community tree ambassadors. Pilot programs were run with Mi Villita Neighbors in South Lawndale, TREEmendous in North Lawndale, and the Roseland West Chesterfield Community Association.

As one of two ambassadors in Mi Villita, Garduño Maya talks to neighbors about the benefits of trees, misinformation about trees, and how to contact the city to get a tree planted for free through the city’s app, CHI311. During the first four months of the program, Garduño Maya facilitated the planting of 237 trees.

To educate and engage interest, Garduño Maya drops off a card that she designed with information about trees’ benefits. The card also addresses misunderstandings, such as the belief that tree roots damage sewer lines and sidewalks. The cards are printed in Spanish and English.

Among the importance of trees, Garduño Maya cites neighbors’ ability to go outside and “feel fresh” as well as be able to walk the streets, which she says can be problematic, especially in hot weather. “My husband and I are big walkers. I love to see the leaves, feel the air. I can feel the difference walking one street to the next. Trees make the difference: the colors, the leaves, how they smell, and how they grow. They’re amazing, magical.”

In 2022, the city planted 18,728 new trees in public parkways, almost double 2021’s plantings. According to Mimi Simon, director of Public Affairs for the Department of Streets and Sanitation, each tree costs between $500 and $550, depending on the type of tree. Eleven of the city’s priority communities received 33% of these trees. North Lawndale planted 957 trees, Humboldt Park 695, New City 553, and South Lawndale 529. Both North and South Lawndale were participating in the tree ambassador pilot program.

Cooling the heat islands

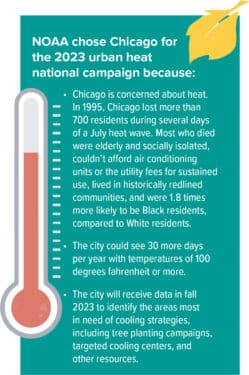

Related to air quality is the urban heat island effect. “Typically the urban core is hotter than the surrounding areas because it is filled with materials that absorb heat and then reradiate it at night,” says Hunter Jones, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) program manager for the National Integrated Heat Health Information Service. He says that in replacing trees, green space, and water with concrete and other related materials, we lose our cooling infrastructure.

This is detrimental to human health. Heat is the no. 1 weather-related killer, according to NOAA. “It is known as the silent killer or the invisible killer because of the damage it does,” Jones says. Exposure to extreme heat can cause heat illness — dehydration, heat cramps, headaches, heat exhaustion, and heat stroke — as well as accelerated death from respiratory and cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases, including mental health and kidney disease, according to the World Health Organization.

“We [NOAA] are making heat visible by conducting Urban Heat Mapping Campaigns to show where heat is being experienced differently within and across neighborhoods,” Jones says. “We know that the intensity, duration and frequency of heat events is getting worse. It’s important to know that a lot of heat impact happens on moderately hot days, too.”

Trees offer one solution. “Trees provide a tremendous amount of cooling benefits, from shade to releasing little water droplets, evapotranspiration,” Turner-Skoff says. “If you look at the under-resourced communities, the areas where trees have not been considered a necessity, those areas are getting incredibly hot, and there are a lot of people in those areas who qualify as vulnerable populations. Areas devoid of trees are going to be hotter, and the human brain is not going to be able to reset and have the calmness that nature provides,” she says.

This past summer, Chicago participated in NOAA’s Urban Heat Mapping Campaign, a citizen science project. CDPH, along with community partners, initiated the application for this project.

At the time, Mansour was looking at the relationship between heat and trees. “One of the strategies for building community resilience is a healthy tree canopy,” Mansour says. As part of the program, citizens cruised the neighborhoods with heat sensors attached to their cars and collected data on heat differentials within and amongst communities. Data from the campaign will help develop land use policies and inform equitable and just social actions.

“Heat morbidity and mortality are preventable,” Jones says. “Be aware of your own personal risk. It’s not just sensitive groups that are impacted. Anybody can suffer from heat illness.”

According to the National Integrated Heat Health Information System, those most at risk to extreme heat include:

• Children.

• Athletes.

• Older adults.

• People experiencing homelessness.

• People with pre-existing conditions.

• Pregnant people.

• Emergency responders.

• Outdoor and indoor workers.

• Incarcerated people.

• Low-income communities.

• People without resources enabling them to adapt or recover from extreme heat.

• Pets.

Stay hydrated, and know the symptoms and signs of various heat impacts and illness. Go to heat.gov for more information.

Children rank high among Garduño Maya’s worries. Research shows, that if children have a view of green trees from their school lunchroom, they are more likely to attend college or have plans for the future.

“If kids walk around in green areas with green trees, they are going to have an increase in concentration, reduced symptoms of ADD and ADHD, and increased attention in general,” Turner-Skoff says.

“With all the benefits that trees provide, they are absolutely a necessity,” Turner-Skoff says. “It should be a core human right to live in a city and have access to nature because of all the benefits it provides. So we need to shift from thinking of trees as a nice-to-have and instead as an investment in our society.”

And in our health. Tree vitamin, anyone?

Above photo by Katie Scarlett Brandt

Originally published in the Fall/Winter 2023 print issue.

Kathleen Aharoni is a movement and life coach, forest bathing guide, and author of the award-winning book I breathe my own breath! She has served on the faculties of Northwestern University and Columbia College.