Wildfires push Chicago air quality to unhealthy levels

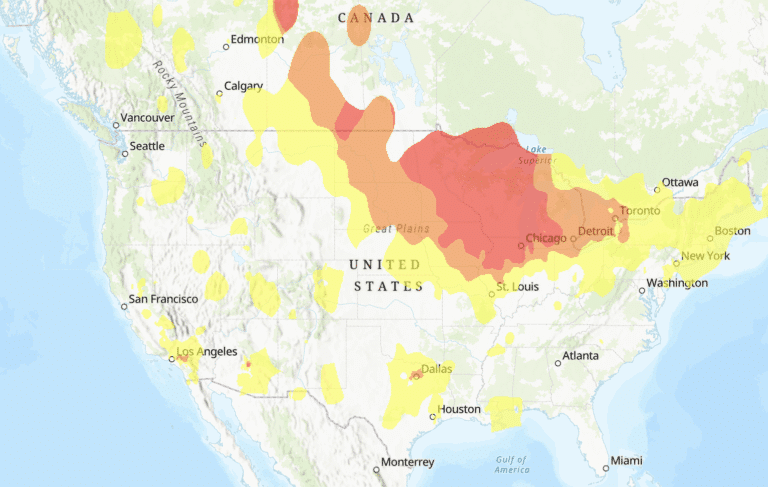

Chicago experienced some of the worst air quality in the world last week as wildfire smoke from multiple wildfires drifted over the area, prompting health alerts and urging residents to limit outdoor activities.

By late Thursday afternoon, the city’s Air Quality Index (AQI) — the federal government’s measure for air quality — peaked at 174. That level is categorized as unhealthy for all individuals, according to AirNow.gov. The Illinois Environmental Protection Agency issued alerts for the Chicago metro area, warning that AQI levels above 150 pose serious health risks, particularly for children, older adults, and people with heart or lung conditions.

“The higher the AQI, the worse the air quality,” says Jerry Krishnan, MD, PhD, a pulmonologist at UI Health. “Once you cross into levels above 150, we call it unhealthy. If you’re in a sensitive group — those with heart or lung diseases, older adults, children, or if you’re pregnant — then you should be limiting your time outdoors and avoiding prolonged, heavy exertion.”

Even healthy individuals should take precautions, he says. “Avoid running or exercising near streets and high-traffic areas. If you feel short of breath, start wheezing, or your heart’s racing, that’s your body telling you it’s too much.”

Fine particulate matter (PM2.5), a harmful pollutant that can penetrate deep into the lungs and bloodstream, drove the air quality warnings. Readings across the city and suburbs exceeded 150 micrograms per cubic meter — far above the World Health Organization’s recommended safe level.

Both the U.S. and Illinois Environmental Protection agencies advised residents to stay indoors, use air purifiers, and avoid strenuous outdoor activity.

Children may be especially vulnerable, says Anne Geistkemper, neonatal and pediatric respiratory clinical manager and a respiratory therapist at Rush University Medical Center. “Kids aren’t fully developed, so you don’t always know how they’ll react,” she said. “If [AQI] alerts indicate moderate to severe risk, we really should be staying inside.”

The smoke’s source

According to Rafal Ogorek, meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Chicago, the smoke is coming from large wildfires in Canada, Arizona, and Utah.

“Most of the wildfire smoke settled into a layer of the atmosphere about 1.5 to 2.5 miles above ground level,” Ogorek says. “Prevailing winds in that layer steered the smoke into the Midwest and the Chicago area.”

Predicting exactly how much smoke reaches ground level remains difficult. “Smoke models are generally good at projecting concentrations aloft, but they’re less accurate in forecasting how much will mix down to ground level,” Ogorek says.

When people breathe in fine particulate matter at ground level, it increases their risk for many health conditions. In humans, studies show that PM2.5 exposure increases people’s risk for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, as well as neurological disorders.

Particulate matter from wildfires and agriculture specifically were associated with an increased dementia risk, according to a 2023 study in JAMA Internal Medicine. The University of Michigan researchers analyzed data from 27,000 adults over age 50.

In the environment, fine particulate matter leads to damage as well. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency reports that smoke makes lakes and streams acidic, depletes the soil of nutrients, damages crops and forests, and more.

This year’s air quality patterns reflect a broader shift, Ogorek adds, saying, “We’ve noticed that wildfire smoke reaching the Midwest has become more common in recent years compared to prior years.”

Krishnan agrees. “I’ve been in Chicago 17 years. I’ve never seen this many poor air quality days. They seem to be increasing in frequency.”

This particular bout of poor air quality reminds many Chicago residents of the Canadian wildfire smoke that drifted over the city in 2023. On June 27 that year, the Air Quality Index reached 209, and the poor air quality persisted for days.

An international issue, felt locally

Wildfires in western Canada have burned more than 6 million acres this year. This marks the second time in 2025 that Chicago has recorded AQI levels above 150 from out-of-state wildfire smoke.

“It’s a combination of things,” Krishnan says. “There are multiple wildfires in Canada that are producing smoke, but it’s also the time of year — temperature and humidity matter.”

Even without wildfire smoke, Chicago faces chronic pollution. According to the American Lung Association’s 2025 State of the Air report, the Chicago-Naperville-Elgin metro area ranks among the worst in the U.S.:

- 15th worst for ozone pollution, with more than 20 days ranked as unhealthy per year

- 13th worst for year-round particle pollution

- Failing grades for both short- and long-term air quality

Marginalized communities, particularly on the South and West Sides, are hit hardest. These areas already have higher rates of asthma and heart disease, making smoke events even more dangerous.

While Geistkemper says she doesn’t see admissions explicitly tied to poor air quality, the connection is likely. “Could air quality be contributing to symptoms? Absolutely. We definitely see more kids with breathing trouble during these high-alert days, particularly those with respiratory disease.”

In pediatric and neonatal ICUs, her team sees a clear pattern. “It happens fast,” she says. “Kids who already have respiratory challenges suddenly can’t breathe and end up in the ED.”

What residents can do

Health experts recommend several precautions during air quality alerts:

- Stay indoors with windows closed

- Use air purifiers with HEPA filters if available

- Avoid intense outdoor activity

- Wear a properly fitted N95 mask if you must go outside

- Monitor updates via AirNow.gov or the EPA’s mobile app

“If you must be outside, N95 masks are extremely effective but uncomfortable to wear all day,” Krishnan says. “Ideally, just limit your time outdoors.”

He also advises keeping indoor air clean: “Close windows, turn on air conditioning if you have one, and use a home air purifier with a HEPA filter.”

Geistkemper urges families with vulnerable members to be prepared. “If you’re in a sensitive group and use rescue medications, keep them with you when you’re out,” she says. “You never know when symptoms will flare, and it can happen quickly.”

Climate action

Experts warn that short-term exposures to polluted air can have lasting effects. “It’s a cumulative dose effect,” Krishnan says. “The more often and longer you’re exposed, the worse the health effects — respiratory problems, heart disease, cancer, and possibly cognitive decline.”

He cites a study by Francesca Dominici of Harvard University School of Public Health that linked short-term pollution exposure with increased death rates. “It’s not just a short-term issue,” Krishnan says. “It’s a long-term risk.”

Krishnan calls for urgent personal and political action. “We need to move away from burning fossil fuels — cars, buses, buildings — and push for cleaner energy, more public transit, and encourage leaders to protect the environment,” he says. “Individually, we can do small things — like carpooling or switching to energy-efficient appliances — that really add up at the population level.”

The EPA offers Pollution Prevention Tips to help lower emissions at home and in the community.

Catherine Gianaro, a freelance writer and editor based in Chicago, has written about healthcare and higher education for more than three decades. With 90-plus awards in communications, she is well-versed in storytelling.