Venezuelan migrant children and the mental health journey they face

This is the story of thousands of families, violently uprooted from their homeland, now struggling to build new lives and opportunities for their children. Schools, community members, and human rights organizations have played a crucial role in addressing their mental health needs and integration. Yet, as these families face ongoing hardships, the strength of those support systems is tested every day.

Over the past year, the After the Darién reporting team has spoken with more than three dozen social workers, psychologists, teachers, frontline organizers, and forcibly displaced families. We analyzed data to assess how mental health needs are being addressed and listened to families share their physical journeys and the emotional toll of displacement.

This project is the work of El Tiempo Latino and Chicago Health magazine reporters, supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism, International Women’s Media Foundation, and Investigative Reporters and Editors.

“It looks like the jungle,” a third-grader with long black hair says to her teacher during a school trip to the Shedd Aquarium. “But there are bigger rocks there. And there are a lot of dead people. I saw it.”

Of the dozens of children on this field trip, most are Venezuelan and have migrated through a dangerous stretch of jungle — the Darién Gap — between Colombia and Panama to get here. The Shedd’s artificial streams, rocks, and humidity remind the children of their journey. “Did you cross the Darién, too, teacher?” The girl asks.

Many of these conversations happen with the help of Google Translate, which the teachers have downloaded on their phones to communicate. None of the children speak English, and they have been placed in a school on the West Side where none of the teachers speak Spanish.

Most of these students arrived in October 2023, overwhelming the front office staff, who did everything they could to meet the demand. An office clerk and a security guard — two of the only Spanish speakers — frantically answered families’ questions, sorted through paperwork parents had brought in sealed plastic bags, and helped place children in the correct grades.

Within two weeks, the school’s enrollment surged by 50%, with more than 100 new students. When staff and parents raised concerns about the influx during local school council meetings, the principal stressed the school’s legal obligation to accept every child under the Education for Homeless Children and Youths (EHCY) Program of the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, which guarantees school enrollment, transportation, and academic support — regardless of whether students have official records.

Like many of Chicago Public Schools’ 634 schools, this West Side school was under immense pressure. School leaders knew they had to find ways to meet the children where they were academically and emotionally. Displaced children have a high risk of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and other mental health conditions. The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre puts the rate of depression and PTSD among displaced people at 30%.

Researchers have been studying how ongoing conflicts globally — such as in Venezuela, Ukraine, the Middle East, and Sudan — impact forcibly displaced children’smental health, as they attempt to integrate into new communities.

One review of studies, published in November 2024 in the journal PLOS: Mental Health, looked at ways forced displacement affects healthcare and global health security. Displaced young people are especially unique, the authors write, “because they are the most vibrant, energetic and dynamic part of the population and form a foundation for a new generation.”

Sharon Hoover, PhD, is a professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. She also co-directs the National Center for School Mental Health. She stresses that when schools invest in mental health programs for their newcomer students — and for all students — the students become better prepared for college and the workforce.

Campus safety improves, too.

“When you put more mental health supports in schools, it actually increases the safety of the campus because it helps to identify challenges early, and certainly helps to identify any threat earlier,” Hoover says. “It improves school climate overall, which leads to more belongingness, more connectedness.

And that’s especially true for students coming in from a new community, a new country.”

Hoover speaks from 25 years of experience with the National Center for School Mental Health. “These are not new issues,” she says. “There’s lots of research that says students are going to better succeed in school and in work and in life if they have accessible mental health and education support.”

MENTAL HEALTH CRISIS

The United Nations urges countries receiving migrants to prioritize mental health care, emphasizing that when children have access to opportunities and resources, most go on to lead healthy and emotionally fulfilling lives with remarkable resilience.

Yet, two reports published at the end of 2024 — by the Pan American Health Organization and Refugees International — highlight critical gaps in the humanitarian response, particularly the lack of services available to children.

Schools and shelters are the primary access points for children’s mental health services. But even before the recent surge of migrant arrivals, the U.S. was in the midst of a youth mental health crisis. In the years leading up to the pandemic, persistent sadness and hopelessness had increased to 40% among young people, with 20% of high school-aged students considering suicide, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“The pandemic era’s unfathomable number of deaths, pervasive sense of fear, economic instability, and forced physical distancing from loved ones, friends, and communities have exacerbated the unprecedented stresses young people already faced,” U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, MD, wrote in a 2021 advisory on youth mental health.

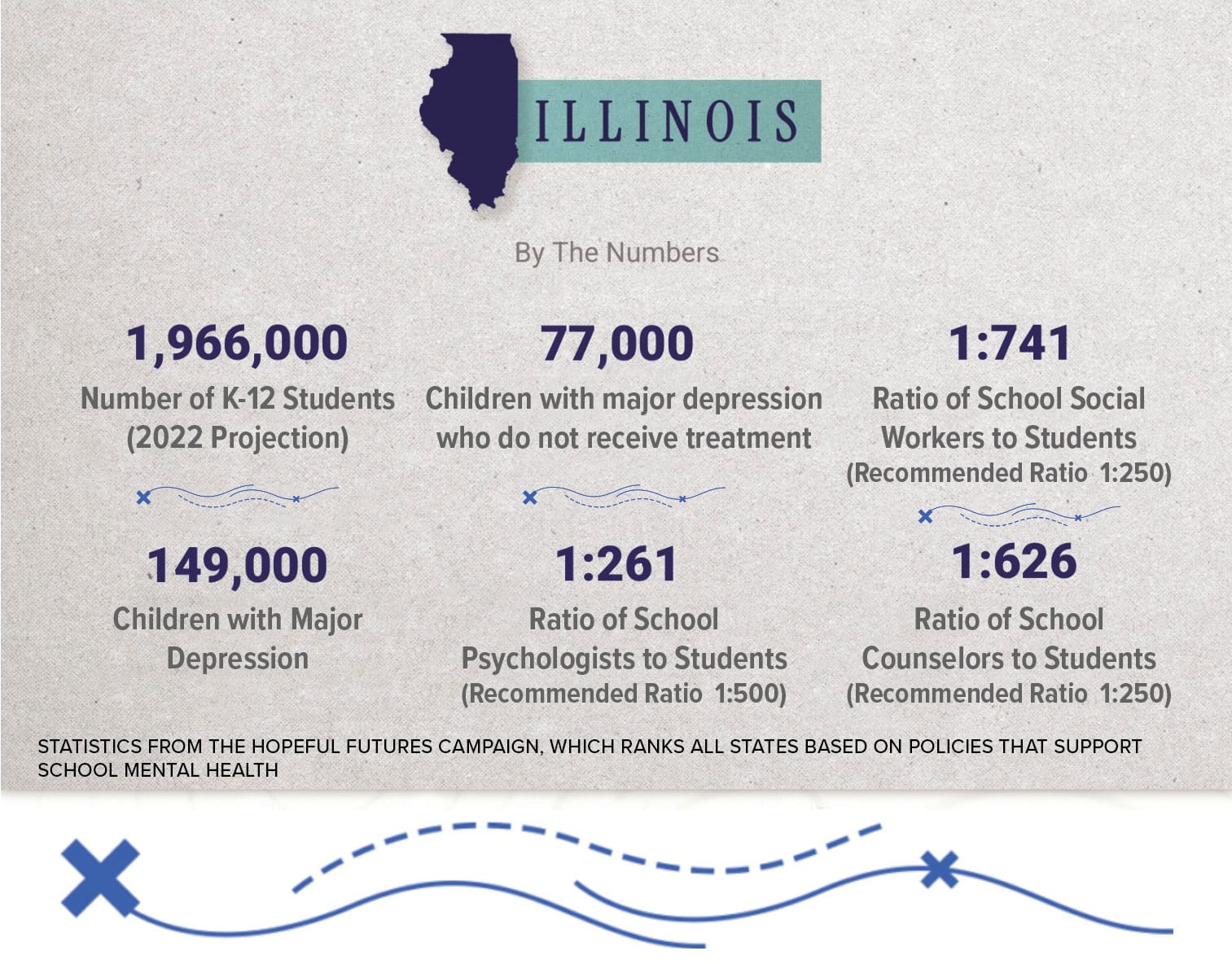

As demand for mental health services surged, the nation faced an extreme shortageof psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and counselors. In 2021, less than half of Americans with mental illness received timely care, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. By 2023, half of the U.S. population lived in areas with a mental health workforce shortage, leading to long wait times or a complete lack of access to care. In Illinois alone, the Association of American Medical Colleges reported that the state’s mental health workforce could meet only 24% of the demand.

Displaced children have a high risk of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and other mental health conditions.

The American School Counselor Association guidelines calls for 1 counselor per 250 students. In reality, the national average sits at 1 counselor per 376 students. And half of America’s public schools don’t provide mental health assessments or treatment services, according to a 2022 Pew Research Center study.

In 2023, Chicago Public Schools reached a ratio of 1 counselor per 364 elementary students, compared to 414 students in 2021. That was made possible after a $15 million Department of Education School-Based Mental Health Services Grant to support credentialed mental health service provider recruitment and retention.

However, school counselor shortages persist due to administrative burdens, low pay, and safety concerns, according to a 2023 report from the American School Counselor Association.

Federal funding remains a critical tool for addressing this crisis. Two key Department of Education initiatives — the School-Based Mental Health Services Grant Program and the Mental Health Service Professional Demonstration Grant Program — aimed to hire 5,400 school-based mental health professionals and train 5,500 more.

With the Department of Education facing significant budget cuts and a threatened dismantling under the Trump administration, those programs — and any like them — are at risk.

NAVIGATING THE TRAUMA

In the weeks after families enrolled in the West Side school in October 2023, the principal launched a weekly support group to help new students connect. This was important, the principal felt, because migrant children face challenges that increase their vulnerability to mental health issues. These issues include:

• Cultural and language barriers

• Discrimination

• Financial strain

• Instability

• Loss

• Separation

• Social stigmas

• Uncertainty

During the first meeting, he asked students, through a visiting translator from the district office, to share their experiences from their journeys.

At first, only a couple of middle school students raised their hands. They spoke about exhaustion from walking for days and the hunger they endured. Then, a middle school girl raised her hand and described the stench of the jungle, the feeling of death all around. Younger students shared stories of sitting on their parents’ shoulders, clinging to their foreheads, as they crossed a raging river.

In the already overstretched and under-resourced school, everyone felt the strain. Teachers juggled the needs of a rapidly growing student body, neighborhood students had to adjust to sharing space and teachers’ attention, and newly arrived children faced language barriers and culture shock.

New students’ general discomfort with being in a strange place, coupled with the stress they had experienced on their journey to the U.S., manifested in a variety of ways in the classroom: hitting, bullying, crying, yelling. And research shows that when teachers feel overburdened, they are more likely to misclassify trauma-driven behaviors as belligerence, which can result in punishments like detentions or suspensions. In fact, during the pandemic, only 65% of educators said they felt comfortable addressing trauma tied to that experience, according to a survey by the American Federation of Teachers.

Hoover says that in thinking about student mental health, planners also need to be thinking about families’ and educators’ mental health.

“Especially in times of uncertainty, or heightened fear, or just change, it’s really important that we’re taking care of the adults so that they can best take care of the kids,” Hoover says. “Student mental health doesn’t happen in a vacuum. The families and educators they interact with everyday are actually the most instrumental. How they’re doing is highly predictive of how young people are doing.”

UNPREPARED SCHOOLS

Even as school counselor ratios have improved in recent years, a new challenge has emerged for migrant students: language. The U.S. not only faces a shortage of mental health professionals, but more than 80% of psychologists and counselors are white, with the vast majority unable to speak Spanish.

“We need to continue our efforts to broaden the array of services and the array of professionals who can provide those services, including identifying providers that best reflect the community being served,” Hoover says. “We could be expanding our array of services to include early intervention for mild to moderate concerns, versus defaulting everyone to mental health treatment. We could do these things more cost effectively if we thought about both of those things — earlier intervention and broader provider array.”

In a trip to Illinois’ Capitol this past spring, teachers met with Illinois State Rep. Lilian Jiménez to advocate for more resources for schools.

“I worry about how this is going to be conveyed to young people, especially since they are moving into neighborhoods like mine that already have high rates of youth violence,” Jiménez says, pointing to widespread unemployment and hopelessness in many low-income areas of Chicago’s South and West sides.

Jiménez observes these children, already lacking resources, witnessing the struggles in their new neighborhoods, including drug dealing. “To bring these new families into this without having processed what they’ve been through — it’s very concerning,” she says. “What can we expect from them in five, 10, 15 years? We can either have a wonderful contribution to our community, or we can have more issues that we need to deal with in the future.”

FINDING BELONGING

Despite lacking resources, schools in the U.S. have become a cornerstone for newly arrived families, helping them build their lives and communities. Those who landed at Carl Von Linné Elementary, a public school on the West Side, found a unique champion in the school’s principal, Gabriel Parra.

High winds and overcast skies were no match for the spirit inside Von Linné this past Halloween. In the front office, Parra — dressed simply in a black pullover sweater and dress pants — carried two large boxes of gummy candies to hand out in the classrooms.

Many of the newcomer students are now in their second year within Chicago Public Schools, becoming more fluent in English and integrating into American culture. They still carry the memories of their journeys, but the students at Von Linné have Parra to help them through.

Four decades earlier, Parra was experiencing his own first Halloween in the U.S. His mother had worked for an American company in Venezuela. When the company offered to relocate her, she immigrated to Chicago with Parra, then 12, and his 2-year-old sister. Parra enrolled in sixth grade at Nixon Elementary School in the Hermosa neighborhood in October 1983.

“I’ll never forget it,” he says. “I spoke no English, knew very little about American culture. I had no idea what Halloween was, and I saw kids dressed up in their costumes. I thought, ‘Where did you bring me, mom?’”

Parra couldn’t have known it then, but he would be exactly where he belonged a few decades later. His journey would connect him profoundly with dozens of Venezuelan families facing similar situations. While many schools at this moment have struggled with mental health resources and support,

Parra is building both.

THE FIRST ARRIVALS

The first calls came from the Chicago Park District and Chicago Public Schools. It was May 2023, and the city was converting the field house at Brands Park into a shelter for migrant families. Dozens of children would need to enroll in elementary school.

How would their arrival impact the school? Parra wondered What resources would the school need?

When the shelter opened, Parra walked over with a team from Von Linné to introduce himself. Shelter administrators led him to an open gym filled with families and children running between numbered cots.

“It broke my heart to see that,” Parra says. “These are my people. It’s not just an understanding of what’s happening in the country and why they’re here, but understanding what it’s like to be an immigrant.”

Parra began by introducing himself to the families and explaining that he and his team had come to enroll children in school. Then, he revealed that he, too, was an immigrant, from Caracas. At that moment, hundreds of people stood up and cheered. Their reaction gave Parra chills.

Initially, 53 new students enrolled at Carl Von Linné Elementary — a school of 640 at the time. Now, there are more than 100 migrant students.

On the students’ first day, Von Linné staff returned to the shelter to walk the children to school. Parents lined the sidewalk, cheering them on. Nearly two years later, many of those first students remain at the school, even though their housing has shifted across the city.

One family from last school year found a home on the South Side, resulting in a nearly two-hour commute to school each morning.

But many students don’t return to their initial schools after they change shelters or find housing in other parts of the city. Rebecca Ford-Paz, PhD, a child psychologist at Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, has seen this happen often.

Ford-Paz provides psychological evaluations for asylum-seeking minors. Once families transfer shelters or find housing, they often move to a new neighborhood — sometimes one with no Spanish speakers. “It’s just a recipe for school dropout,” she says.

Parra spoke with one mother who had just moved to the South Side about her child’s commute, explaining how challenging the trek would be, especially during winter.

“Really?” he recalls her saying. “I walked from South America, through the Darién Gap, to the United States. This is a piece of cake.”

“I had no response,” Parra says. And this year, the student, now in 6th grade, remains at Von Linné.

THE EMOTIONAL JOURNEY

Over time, and on their own terms, many parents and students shared stories from their journeys. The school’s social-emotional learning team developed a questionnaire to gather more individualized data.

The responses painted a clearer picture of the emotional trauma these students had endured. They shared stories of having to jump over dead bodies and encounters with criminal gangs looking to rob and exploit them along the way.

“This is significant trauma for families and children,” Parra says. “We need to focus on the social-emotional side of this, but how do we do that? Their academics are so behind, too; you don’t want to lose time there.”

Since 2023, the school has added two new interventionists and partnered with an outside agency, Journey’s, which provides bilingual counselors.

Parra also meets with other Chicago Public Schools principals, sharing Von Linné’s successes and struggles.

Ford-Paz has noticed that schools often fail to provide adequate accommodations for students who need more support than a mainstream classroom can offer. In some cases, schools disregard families who disclose their child’s autism diagnosis, leaving the student without essential support from day one. Other times, students lack proper social-emotional support because schools assume, “They’re just newcomers — they’ll adjust,” she says.

One new student at Von Linné was 6-year-old Fernanda, who arrived with her adoptive mother, Mari, on a bus from Texas in August 2023. If it hadn’t been for the school, Mari says, their lives wouldn’t be what they are now.

Mari, 44, fled Venezuela in April 2023 after the men who murdered her mother were released from prison and vowed revenge. Their threats were the final straw.

Fifteen years earlier, in 2008, Mari and her sisters had saved up to buy their brother a motorcycle. Soon after, criminals stole it, were arrested, and, in retaliation, came looking for him — finding their mother instead.

Mari fought for justice, ensuring the killers were jailed. But during their imprisonment, tragedy continued: her sister and brother-in-law, both chronically ill, died, leaving behind their infant daughter, Fernanda. Mari raised her as her own.

When her mother’s killers were freed, she and Fernanda fled.

Their journey through Colombia, the Darién Gap, Panama, and Mexico mirrored that of thousands of displaced people. They were robbed, went without food for days, and feared for their lives. Fernanda was exhausted and hungry, but one promise kept her going: Mari had told her they would see Mickey Mouse’s house at Disney World.

The family entered the U.S. after 14 days waiting in Mexico, using parole obtained through the Customs and Border Patrol’s immigration enforcement agency, CBPOne. Then, they boarded a bus to Chicago.

CULTURAL CARE

The Venezuelan families who have acclimated most successfully to life in the U.S. tend to have one thing in common: the support of other Venezuelans. Those already established in cities like New York and Chicago have built crucial support networks, much like other Latino communities with a long history of forced migration.

At Von Linné Elementary, Parra’s efforts are one example. Similarly, the Illinois-Venezuela Alliance works relentlessly to reach displaced Venezuelans where they are, offering counseling sessionsin shelters and serving as expert witnesses in immigration cases involving trauma.

At first, there was solidarity. But as more buses arrived, city resources — and the people trying to help — became overwhelmed.

The city’s crisis reconnected Ana Gil, a Venezuelan teacher living in Chicago, with her purpose. “No one can understand a Venezuelan woman better than a Venezuelan woman,” she says. Most migrant women, she adds, never wanted to leave their country. “There is a lot of frustration and a lot of pain.”

When everyone around you shares that pain, it can feel normal. “They don’t see it as a problem. They just see it as — this is life,” Ford-Paz says.

Many cultures don’t have the same concepts of mental health that Americans do. “Some cultures don’t even have a word for depression or post-traumatic stress disorder,” Ford-Paz says. “Unless there’s some sort of raising awareness that things can be better, and there’s help available, there’s going to be limited engagement in our traditional systems of care.”

Stigma plays a role, too. “People will want to try everything else before they would ever go see their doctor about it. They’ll go to their clergy person, and they’ll get a cleansing. Or they’ll go to the botánica or see a curandero,” Ford-Paz says. “There’s a number of things that are culturally more congruent and more familiar that they’re going to exhaust before they would consider talking to a mental health professional.”

When their children started school in the U.S., most parents didn’t know they could advocate for mental health support.

“There’s a lack of familiarity with our system of care here that it’s even an option or that there are social workers in school buildings,” Ford-Paz says. “People don’t know what they don’t know. They don’t know how to ask or where to ask for help.”

For many families, survival takes priority. “Where are we going to live? How am I going to put food on the table? Until those basic needs are met, the ability to really engage in mental healthcare is limited,” Ford-Paz says. “We need to integrate primary and mental health care so they don’t need to make a separate appointment in a stigmatized setting.”

Raising awareness about school-based services is one goal. But now, schools, hospitals, and churches — once trusted as protected spaces from immigration enforcement — are sources of fear. The challenges for those trying to help have only grown.

Hoover stresses that programs that are helping students and families transition to new communities need to persevere. “It’s really important not to abruptly stop mental health services and to make sure that our health settings are accessible and that people are not fearful of getting support,” she says.

Because when people fear going to school or their medical appointments, everyone stands to suffer. Hoover imagines the economic disaster that awaits if people end up avoiding care until health issues get out of control.

“If we really care about the bottom line and creating safer and more productive communities, you want to continue services that support people’s mental health and education,” Hoover says. “Those are not the things to cut off in this moment in time. Maybe we can increase our understanding of return on investment, put things in place to make school mental health services more efficient, but don’t just stop services.

Parra thinks of his own mother, who brought him to the U.S. hoping for a better life.

“I’m grateful that she instilled those values and those morals in me, that she prepared me to thrive and be able to achieve my dreams,” he says. “I never imagined that I would be sitting here as the principal of this school, but it happened.”

He holds the same hope for his children — and for those who have traveled so far in search of education and a future. “If they are going to embrace this wonderful country that is America, whatever they learn here, the foundation they received here at the Linné School sets them up for success so that they can be good citizens and embrace the American dream, which I am living.”

A year after her journey through the Darién, Fernanda is clinging to her dream of seeing Mickey Mouse’s house. Her mother, in March, was still saving up.

Photo at top by Joel Angel Juárez.

Originally published in the Spring/Summer 2025 print issue.

An award-winning journalist, Katie has written for Chicago Health since 2016 and currently serves as Editor-in-Chief.

Clavel Rangel is a Venezuelan journalist and co-founder of the Network of Journalists from the Venezuelan Amazon.