Eggs without an expiration date offer women fertile hopes

Starting at age 30, women may hear their biological clock ticking. It ticks louder with each passing year; each tick a gradual decrease in fertility. By your mid-30s, it’s so loud that it’s tough to ignore if you’re hoping to have children.

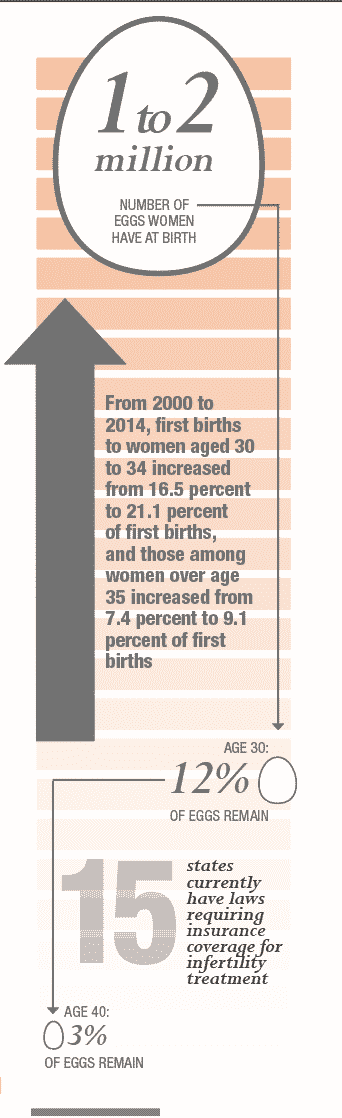

When women hit 35, the odds of reproductive risks such as miscarriage and Down syndrome become higher, and ovarian reserves become lower. At birth, a woman has between 1 to 2 million eggs. By age 30, 12 percent of her eggs remain. And by age 40, only 3 percent are left.

“When it comes to reproduction, time is not our friend,” says Jennifer Hirshfeld-Cytron, MD, reproductive endocrinologist at Fertility Centers of Illinois.

But what if you stopped the clock? What if you froze your younger, healthier eggs to use when you were ready for a family? Your time-consuming career could continue; you could finish your educational path; you could search for a mate sans deadline—all while your younger eggs sit in reserve until you’re ready to get pregnant.

“The ability to freeze eggs is transformative by helping women consider life decisions,” says Angeline Beltsos, MD, CEO and medical director of Vios Fertility Institute Chicago. “Women take charge of their career and relationships, and now they can take charge of fertility.”

For years women have been freezing eggs for medical reasons, including cancer, pre-cancer, genetic concerns and early menopause. But now, more women are freezing eggs as they focus on their career, education or search for a life partner.

“I didn’t think I would be 36, single and without children, but there I was,” says Chicago resident Amanda Delgado. “Freezing my eggs at 36 put my mind at ease while helping me feel empowered.”

Delgado, now 40, is mother to her first daughter, Charlotte. And even though she’s a single mother, she’s not alone. Women having babies later in life is a national trend.

From 2000 to 2014, first births to women aged 30 to 34 increased from 16.5 percent to 21.1 percent of first births, and those among women over age 35 increased from 7.4 percent to 9.1 percent of first births, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“There’s no question that there is a substantial increase in women freezing eggs,” says Mary Wood Molo, MD, director of the in-vitro fertilization (IVF) program at Rush University Medical Center. The technology is more mainstream now, she says.

Over the past five years, a new rapid egg freezing technology called vitrification has radically improved success rates.

When freezing eggs, the formation of ice crystals within the egg can damage or destroy the egg. “With vitrification, there is less ice formation and better survival and pregnancy rates,” Wood Molo explains.

The process of collecting eggs starts with blood work and an ultrasound, and it continues with two weeks of self-administered medications that stimulate the ovaries to produce as many eggs as possible. During this time, there are follow-up visits to closely monitor developments and hormone levels. About eight to 14 days later, the eggs are retrieved in a 20-minute procedure while the patient is under gentle sedation.

“Our goal is to retrieve 12 to 15 mature eggs to improve the odds of a successful pregnancy,” Wood Molo says. “If a woman is a carrier of a genetic disorder, then the goal can be higher.”

Either the egg can be frozen and it can be fertilized later when it is thawed, or the egg can be fertilized with a partner’s or donor’s sperm and an embryo can be frozen.

The chances of becoming pregnant aren’t a sure shot. “There is no guarantee that the eggs will survive the thaw and ultimately result in a pregnancy,” Wood Molo says. “Appropriate counseling is important so that each patient is given data specific to her age and ovarian reserve. It’s important to be realistic and not give women false hope.”

When unfertilized eggs are frozen, about 90 percent of them will survive freezing and thawing, and about 75 percent will be successfully fertilized, according to the Mayo Clinic. Depending on your age at the time of egg freezing, there is a 30 to 60 percent chance of becoming pregnant after implantation of an embryo formed from previously frozen eggs.

When embryos are frozen, between 95 to 98 percent of them survive the thaw. Pregnancy rates are dependent on the age and quality of the embryos at the time of freezing, Wood Molo says.

For Delgado, the retrieval cycles were successful but emotionally taxing. “You want to get as many eggs as you can,” she says. After the egg retrieval, she experienced side effects including bloating and cramping, but she says she remained focused on the outcome: a beautiful baby. “There was an immediate sense of relief after the retrieval. It truly took the pressure off,” Delgado says.

In her first retrieval, Delgado retrieved and froze 12 healthy eggs, which she calls her “dirty dozen.” Then when she was ready to get pregnant two years later, she went back for a second retrieval. This time it was more than egg freezing; she also underwent IVF to try to get pregnant. Her doctor retrieved more eggs and fertilized some using a sperm donor. On her second round of IVF, Delgado successfully became pregnant with one of the embryos.

Delgado still has 12 eggs and four embryos frozen. Since she was single, she used a sperm donor for the embryos, but she also froze unfertilized eggs in case she later finds a partner whose sperm can be used.

After women have frozen eggs, it’s important for them to stay healthy, eat right, exercise, manage stress and stop smoking. After all, there are still risks associated with pregnancy at an older age, including delivering prematurely, requiring a C-section, having high blood pressure and developing gestational diabetes, Hirshfeld-Cytron says.

The process can be quite expensive. One round of egg retrieval can cost upwards of $10,000, and sometimes it takes more than one cycle to get the optimal number of eggs. “It’s not cheap,” Delgado says, “but the cost was worth it for my future.”

As for insurance helping with the bill, currently only 15 states, including Illinois, have laws requiring insurance coverage for infertility treatment. But the laws don’t always cover egg freezing, which can be considered elective. Some progressive employers cover comprehensive reproductive strategies: Apple, Facebook and Intel recently added egg freezing to their female employee benefits.

As Delgado’s baby, Charlotte, turns 1, Delgado scheduled an appointment to meet with Wood Molo to discuss planning for baby number two.

“It’s reassuring to know you have the option to have a baby much later than you did before,” Delgado says. Her clock keeps ticking, but it’s a little quieter now.

Originally published in the Spring 2017 print edition