As infections and low egg supplies persist, avian flu remains an unpredictable health concern

Soaring egg prices, purchase limits, empty shelves — since January, Americans who shop for eggs know the scene well. And as the ongoing bird flu outbreak rages, there’s no end in sight.

The avian flu, or bird flu, has been wreaking havoc in the animal world, says Robert L. Murphy, MD, executive director of the Havey Institute for Global Health, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. Since this version of the avian flu virus (H5) first appeared in the U.S. in 2016, nearly 170 million birds have been affected in on-and-off outbreaks.

“It’s quite devastating to birds,” Murphy says. “It can infect and kill other animals. It can kill humans, but the transmission to date is only animal-to-man.” Health officials have yet to observe human-to-human transmission in the U.S., though the Trump administration’s crackdown on immigrants is making tacking the disease in humans more difficult for healthcare workers. People fear talking with strangers or leaving their homes, health workers report.

Advocates warn that fear of deportation may prevent early detection and reporting of avian flu exposures, particularly in rural areas across the Midwest, where immigrant labor is essential to poultry and dairy operations. This hesitancy could leave health departments in Illinois and nearby states flying blind if the virus begins to spread more widely among workers or into surrounding communities.

“There’s a strain, D1.1, that appears maybe a little bit more severe,” Murphy says, referring to a variant that has caused at least one death in Louisiana and a serious case in a teenager in British Columbia. Murphy also stresses that the virus continuously mutates, creating new strains that add to the uncertainty of its future path.

Health officials are preparing vaccines for such scenarios. “There are several vaccines that have been authorized for humans that work for avian flu,” Murphy says. “They’re being stockpiled.” Vaccination efforts are currently more focused on those directly exposed to animals, such as poultry workers, rather than the general public. “The real challenge is that we really don’t know how much of this virus is [circulating] in the animal world.”

One of the biggest hurdles in understanding the actual threat of avian flu is the lack of animal surveillance. For most humans who have had an infection so far, avian flu has presented like the seasonal flu (including fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches, and fatigue). But it also can progress to more severe complications, such as pneumonia.

In the U.S., fewer than 100 confirmed human cases have been reported, with only one death so far. The situation in some countries, such as Cambodia, has been more dire, with recent reports indicating more fatalities. The World Health Organization reports that 24 countries confirmed 954 human cases of avian flu from 2003 to 2024. Of these, 464, nearly 50%, were fatal.

In Illinois, the risk to the general population from the virus remains low, with no confirmed human cases as of April 26, according to a statement from the Illinois Department of Public Health (IDPH). However, there have been cases on poultry farms in the state and among wild geese and other waterfowl. While avian flu has impacted dairy cattle in some states, it had not affected cattle in Illinois as of April 26. IDPH says it has been actively monitoring the situation.

There are some challenges to diagnosing avian flu. While large commercial labs can test for it, if the virus begins to spread more rapidly among humans, current laboratory capacity won’t be able to keep up. The CDC has begun working with commercial labs to build additional tests. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently issued guidance requiring labs to check influenza A tests for avian flu, but the mandate doesn’t extend to outpatient settings, such as urgent cares.

While flu rates in humans decrease across the country in spring, avian flu is more unpredictable, due to factors including climate change, and the shifting nesting and migration patterns happening as a result. It remains unclear if rates will decrease as the weather warms.

“If this mutates anymore, this could be the next pandemic,” Murphy says. Pharmaceutical companies, particularly Moderna, are developing vaccines targeting strains like H5N1.

Should the virus evolve to spread more easily among humans, it could quickly lead to a global health crisis. Murphy acknowledges the fear surrounding this, particularly as millions of dollars go into vaccine development. “They’re even looking at vaccinating birds,” he says.

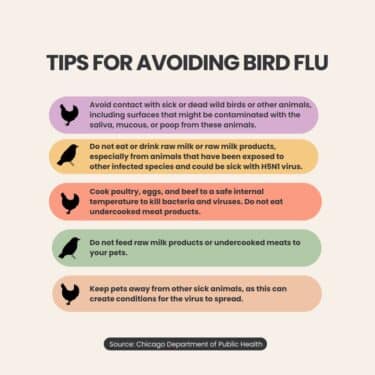

If you see five or more deceased birds in one location, the Chicago Department of Public Health advises people to notify the Illinois Department of Natural Resources or USDA Wildlife Services at 1-866-487-3297. The Illinois Department of Agriculture handles reports of sick or dead domestic poultry.

Catherine Gianaro, a freelance writer and editor based in Chicago, has written about healthcare and higher education for more than three decades. With 90-plus awards in communications, she is well-versed in storytelling.