Staying up all night. Constantly refreshing the webpage. Trying to book an appointment for the Covid-19 vaccine in Chicago has looked a lot like scoring tickets to your favorite band’s concert.

Ashwini Deshpande of Vernon Hills struggled for nearly one month to book appointments for her 77-year-old grandparents, who live in Chicago. With overloaded call centers for Cook County vaccines, she and her family — five people in total — tirelessly reloaded the ZocDoc website every hour on their phones and laptops until they finally secured two appointments through the University of Illinois Health System.

“Ninety-nine percent of the time there was nothing available,” she says. “It was not what you’d expect for a hospital system that big.”

Deshpande’s experience mirrors that of thousands of other Chicago-area adults and essential workers eligible for the Covid-19 vaccine. Even the city’s mass vaccination sites, which can inoculate hundreds every day, have had only scarce appointments available.

Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH) and other city leaders say equity is at the forefront of Chicago’s vaccine rollout plan, yet the vaccines still have not reached all at-risk residents who need the vaccine the most.

Rocky roll out to at-risk communities

The city quickly learned that equity requires more vigilant efforts than simply housing vaccine sites in vulnerable neighborhoods.

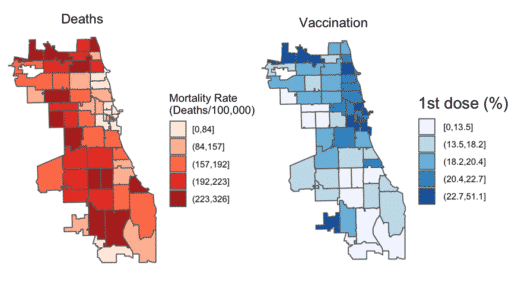

While Chicago officials placed four of its original six mass vaccination sites in city colleges on the Southwest Side, where Chicago’s residents hardest hit by the virus live, people who live outside of those communities snatched up many of the spots.

Loretto Hospital, in Chicago’s Austin neighborhood, was the first hospital in the city to administer the Covid-19 vaccine. Yet, not all of its doses have gone to the neighborhood’s vulnerable residents. Executives at the hospital arranged for vaccinations at a variety of places outside the neighborhood, including a suburban church that a Loretto executive attends, a Gold Coast steak house, and at Trump Tower, where one hospital executive lives.

Public health and policy experts, city aldermen, and community advocacy groups have called on the city to make targeted vaccine distribution plans for the zip codes that Covid-19 has hit hardest. They’ve requested a set number of vaccines for those areas, along with plans to leverage the people and places the community trusts to distribute them.

They’re also working to craft policies that make vaccine sites more accessible to communities of color. Ald. Byron Sigcho-Lopez, 25th Ward, introduced to City Council the “Take the Vaccine to the People” ordinance, which proposes establishing at least one public vaccination site per square mile in any Chicago community. The ordinance calls for an expansion of vaccination sites to include public spaces such as election polling sites, as well as vaccine appointments available 12 hours a day, seven days a week through the CDPH multilingual call center. The ordinance was sent to the Committees and Rules committee, where it will undergo a vote for further action.

According to data from the city of Chicago as of April 6, 39.5% of first-dose Covid-19 vaccines have gone to Black and Latino Chicagoans, despite making up 59% of the city’s population.

Bypassing those with the greatest need

The Federal Emergency Management Agency has stepped in to help, running the mass vaccination site at the United Center. Located just west of the Loop, it has the capacity to vaccinate 6,000 people daily. Like several other mass vaccination sites, the signup process proved chaotic for many. At its peak, 754 appointments were booked per minute, city officials announced on March 8.

Officials hoped the size and location of the United Center site would accelerate vaccination rates of Black and Latino communities hardest hit by the virus. But of the initial appointment slots made available to Illinois seniors 65 and over — approximately 40,000 — just 37% went to Chicago residents. And 75% of the people who snagged the first appointments were white and Asian.

“Mass vaccination sites are all glitz and glamour, but in reality they’re not addressing the issue at hand. They aren’t improving access,” says Marina Del Rios, an emergency medicine physician at the University of Illinois in Chicago. “Not in the way they are set up.”

Internet-based registration systems favor those who have the luxury of internet access, ample time to wait for available appointments, and safe transportation to vaccination sites — the affluent and privileged, Del Rios says. “That’s not what we generally see in Black and Latino communities.”

After the initial registration fiasco, the United Center restricted eligibility by zip code. Still, inequities and lack of access remain.

“People shouldn’t have to refresh links constantly or wait up all night to get a vaccine,” says William Parker, MD, a pulmonary critical care specialist at the University of Chicago Medicine. “There’s not an ethically sound reason to create a system around that.”

Racking up inoculations without an intentional focus on equity has a cost, especially when vaccine supply continues to be limited, Parker warns.

“It’s important to pour the water where the fire is burning,” Parker says. “We don’t have unlimited vaccines, obviously, so we have to distribute it in a way that will save the most lives and prevent the most infections.

Prioritizing high-risk communities

The city’s vaccine equity campaign, Protect Chicago Plus, partners with community ambassadors to push vaccines and city resources into 15 high-need neighborhoods, as determined by the city’s Covid-19 community vulnerability index.

Belmont Cragin, Gage Park, and North Lawndale were the first communities to host vaccination drives through the effort. The drives’ impact became apparent very quickly, as the percentage of residents who received their first dose of vaccine skyrocketed.

When these communities had low vaccination rates earlier this year, many skeptics were quick to blame vaccine hesitancy and lack of interest as the primary reason for the severe disparity. But the success of place-based vaccine drives in these communities suggests that this isn’t necessarily true, Parker says.

Public health leaders in Chicago commend the Protect Chicago Plus effort, which includes undocumented residents.

“Actually saying out loud that undocumented residents can get the vaccine and prioritizing communities that are victims of structural racism is a really good start,” Del Rios says.

But experts say more can be done beyond pop-up vaccine clinics, especially as vaccine flow remains low and the state expanded eligibility to residents 16 and over on April 12 statewide and April 19 in Chicago. Critics say that permanent vaccination clinics and a more robust public health system would make a bigger impact.

Instead of a first-come, first-served system, Del Rios, Parker, and many others through the Illinois Medical Professionals Action Collaborative Team (IMPACT), are advocating for a weighted lottery system based on age, patient history, and location. Community members from neighborhoods hardest hit by Covid-19 would get higher priority for an appointment.

Del Rios also proposes that the city partner with community clinics in the hardest hit areas who have not been getting enough vaccine supply. Trusted providers in communities of color would help assuage concerns causing vaccine hesitancy and bridge the gaps for patients who experience technology or language barriers, she argues.

“It’s easy to just set up a website and hope people will sign up. It takes a little more effort to do the active outreach,” Del Rios says. “But in the end, it will save lives.”

This will remain true in a post-Covid world too. Del Rios says investing less in automated systems and partnering directly with community clinics will have the greatest impact in improving health disparities that existed long before Covid-19, such as diabetes, obesity, and heart disease.

“What really worries me is that the infrastructure we’re setting up is only going to be temporary during the pandemic,” Del Rios says.

More strategies for community outreach

As the city struggles to find its footing, community ambassadors are deep in the fight against Covid-19. In Little Village, community health workers — often residents themselves — are navigating residents through the vaccine registration process, helping some to create e-mail addresses, giving others directions to vaccination sites, and serving as ushers or registration specialists at the sites. They reach out to friends and family as well as meet community members in public spaces, including grocery stores, pharmacies, parks, and libraries. But some residents are still left out.

“We need strategies to engage more people faster,” says Katya Nuques, executive director of Enlace Chicago, an organization that convenes, organizes, and builds the capacity of Little Village stakeholders to confront systemic inequities and barriers to economic and social access. “I think we need to be really mobile … and go directly to people, even to their homes, to get the vaccine in their arms.”

Little Village opened its Protect Chicago Plus vaccination site on March 3. Esperanza Health Centers runs the operations at Enlace’s headquarters, located at 2759 S. Harding Ave. It’s the third mass vaccination site Esperanza has opened this year, after successful campaigns in Brighton Park and Gage Park. It’s expected to close by early May as the Protect Chicago Plus program ends in Little Village.

Esperanza hopes to vaccinate up to 1,900 people every week in Little Village. To streamline making an appointment and address technology barriers, community members age 18 and over who live in Chicago Lawn, Little Village, Englewood, Archer Heights, Back of the Yards, or Gage Park can call Esperanza’s main number at 773-584-6200 to schedule an appointment or text “VAX“ to 773-207-3133. A representative will call them back to set up an appointment.

While a call center undoubtedly gives more people access to scheduling an appointment for the vaccine, it’s not without challenges. Call centers are easily overwhelmed, and a call back from an Esperanza representative can take anywhere from 48 to 72 hours. Also, Little Village residents often do not answer calls from unknown numbers, says Jackeline Oritz, a community health worker at the Telpochcalli Community Education Project.

“We need more phone lines, [more] multilingual operators, and enough people answering the phones,” Ortiz says, in Spanish. “People are desperate.”

Vaccine supply uncertainty

Manav Seva Mandir, a Hindu temple located in Bensenville, one of Chicago’s western suburbs, opened as a vaccine site for its predominantly South Asian senior community in late February. Its members echo many of the same concerns experienced across the city: Whether you’re young or old, navigating online appointment systems requires internet literacy and tenacity.

“At a certain point, people get tired of trying [to get an appointment for the vaccine],” says Bhasker Patel, chair of Manav Seva Mandir. “Before we ran this campaign, I tried to make an appointment for myself and eventually gave up.”

Manav Seva Mandir partnered with PRISM Medical Group and the Federation of Indian Seniors Association to open the site, where it has hosted two campaigns so far and vaccinated nearly 700 seniors.

For both weekend campaigns, Patel and his team at the temple were notified they would be getting vaccines just a few hours before the shipments were expected to arrive. As soon as the team found out, they called community members to ask who still needed a vaccine and who was available that day for an appointment.

A Saturday evening vaccination campaign on February 27 lasted until 5 a.m. Sunday morning due to vaccine delivery delays. Volunteers stayed through the night, calling people and asking who was willing to come get their shot. People came as late as 3 a.m., and not a single vaccine went to waste.

“These seniors have been trying to get the vaccine for so long that whenever they got the opportunity, they were going to take it,” Patel says.

Patel does not know if or when the temple will receive its next shipment, leaving many community members half-vaccinated and stuck in limbo.

“There’s just not enough vaccines right now for everyone. Hopefully, we’ll get our next shipment soon,” Patel says.

Many of Chicago’s providers lag even further behind. As the city’s positivity rate climbs, public health leaders advise state officials to delay eligibility expansions and instead give vaccines to city providers, giving vulnerable Chicagoans a chance to catch up to the rest of the state.

Vaccines shortages are just one hurdle to equitable distribution. It takes intentional work to implement policies that combat other structural barriers like geography, transportation, language, and technology gaps, Del Rios says.

“We’re seeing good conversation and good intentions moving forward, but there’s still a lot of work to do,” Del Rios says.

Meanwhile, Deshpande’s grandparents received their second dose of the vaccine through the UI Health. Fully vaccinated, they now have a new sense of safety and hope for the future.

“My grandparents were ecstatic,” Deshpande says. “Knowing how difficult the process was and how much time was spent, it was the biggest relief.”

Shivani Majmudar is an M.D. Candidate at the University of Illinois College of Medicine (anticipated graduation in 2025) with a concentration in Global Medicine. Her interests include health disparities, eye health equity, medical journalism, and women in medicine.