Organizations provide equipment and leadership development, promoting independence and power

We hold on to household items for various reasons. We may not want to dispose of them because they evoke memories from the past or because they may be of use in the future. Often, these items are tiny trinkets, cards, or mementos. Sometimes, they are walkers or wheelchairs.

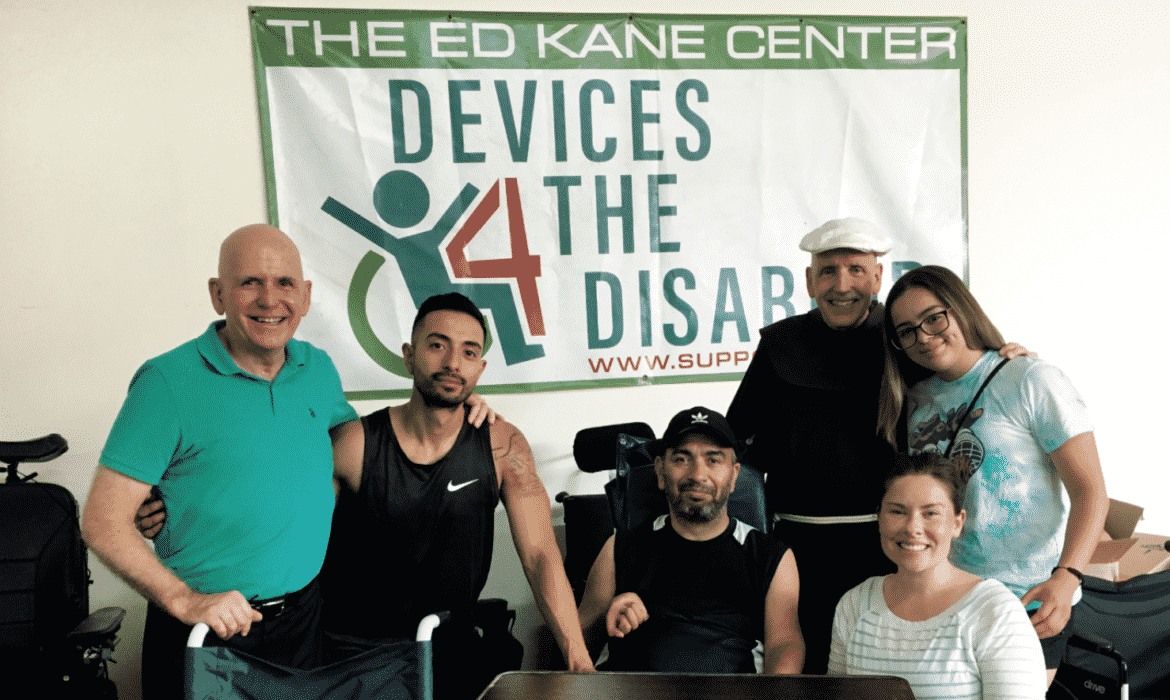

Bob Shea, executive director of Devices 4 the Disabled, recalls the parents whose teenage son used a tilt wheelchair before he died. The father couldn’t let the chair go. “It stayed in the boy’s room,” Shea recalls.

On the anniversary of the boy’s death, his parents visited their son’s gravesite and told him they were going to put his wheelchair to good use. They had decided to donate it.

The family contacted Devices 4 the Disabled, and Shea showed them the organization’s 6,000-square-foot warehouse in Chicago’s Brighton Park neighborhood. There, walkers, canes, hospital beds, and other durable medical equipment get a new lease on life thanks to the generous donations of people who no longer need them.

Devices 4 the Disabled refurbishes the items and provides them for free to those who need them — mostly adults and those who are uninsured, underinsured, or otherwise unable to afford the expensive equipment. The “4” in its name refers to the four tenets of the organization: independence, mobility, dignity, and freedom.

“Just five years ago, we were a couple of guys and a storage locker,” Shea says.

Shea and his friend Ed Kane co-founded the Chicago-based nonprofit shortly after both were diagnosed with neurological diseases. Kane — a former rugby player, vice president of a bank, and married father with four children — found himself withdrawing money from his 401(k) to pay for a complex $30,000 wheelchair when his ALS disease progressed.

Kane’s insurance, he quickly learned, would only cover $2,500. He wondered how people without savings were able to access the equipment they needed.

Many are in such a bind. In Cook County, more than 540,000 people — about 11% of the population — have a disability, according to 2019 U.S. Census data. And many of those need adaptive equipment.

Shea and Kane saw an opportunity to make a difference. They quickly learned that often, when someone is done using equipment — whether crutches or a wheelchair — they keep the item in a basement or garage because they don’t want to throw it out and don’t know where to donate it.

“It was a logistics problem,” Shea says. The supply existed — and so did the demand.

The pair founded Devices 4 the Disabled in 2015, storing initial donations in a church basement. The organization moved to the warehouse almost three years ago. After Kane died from ALS in 2016, Shea continued to collect equipment and financial donations, coordinating with social workers, therapists, nurses, and other healthcare professionals from Chicago- area hospitals and clinics who refer people in need.

In the first six months of 2021, 197 people donated more than 800 pieces of medical equipment, and 282 people received 576 pieces of medical equipment.

Fostering leaders

People with disabilities face more than equipment issues, though. They need access to representation and power to ensure their voices are heard.

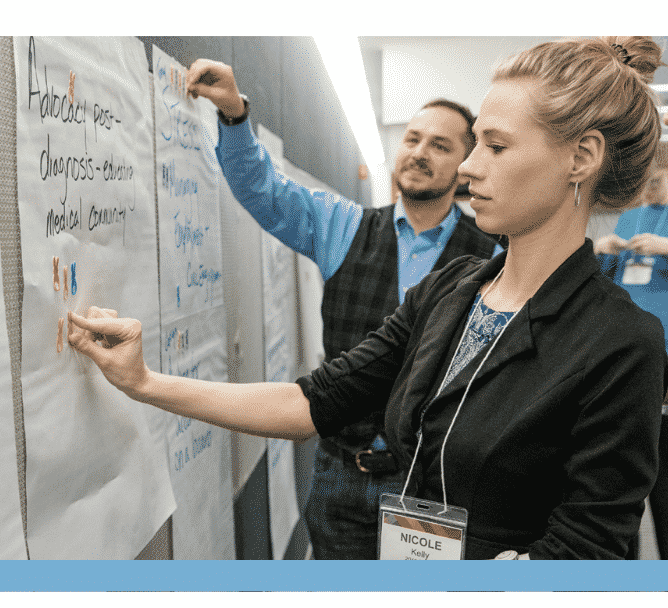

Emily Blum serves as executive director of Disability Lead — a Chicago-based nonprofit network that works toward fostering an equitable and inclusive society by developing power and leadership roles for people with disabilities.

Power, influence, and change are at the core of the organization, which in 2021 changed its name from ADA 25 Advancing Leadership.

The work of Disability Lead revolves around advancing opportunities for its 170 members and raising awareness around disability issues, including holding community events like its Disability Power Series, conversations with disability thought-leaders and change-makers.

It also connects its members with leadership positions on nonprofit boards and public service positions where they can make a difference.

“Our leaders represent,” Blum says. “When they go into spaces, they flex that disability identity.”And people can use their disability identity to shape a more inclusive society, she says.

“Simply put, when leaders with disabilities are at the table and are part of decision-making groups, the results are ideas and solutions that benefit everyone,” Blum says. “The easiest example are curb cuts [in sidewalks]. The disability community in cities across the nation fought to make sidewalks more accessible for wheelchairs. Their voices were heard, and their ideas were centered in planning. And now, everyone benefits — moms with strollers, travelers with suitcases, bikers, and others.”

Blum cringes at the term “differently abled.” Instead, she wants to focus on the strength of disabilities.

Disability is polarizing word for many, but not for Blum. “Society tells us that naming someone as disabled is impolite. But I reject that,” she adds. “My disability is an important part of my identity as much as is being a woman, being a Chicagoan, being a wife, and being a puppy mom.”

“What if disability was the same as ‘Hey, I’m in my 40s. I’m a woman. I’m a white woman. I’m a white woman with a disability?’ How do we take the power back of that word?” Blum asks.

Each of us has a connection to someone with a disability, Blum says. We may have a disability ourselves, or we may have a loved one with a disability. We may work with someone, go to school with someone. And they need to be heard.

Organizations like Devices 4 the Disabled are helping to provide freedom and support to those in need, while Disability Lead provides members with the resources and opportunity to advance inclusion and equity.

Both are fostering independence and creating new possibilities in their own powerful ways.