When Angelina Jolie Pitt had a double mastectomy in 2013 to prevent breast cancer, Chicagoan Carolyn Kirschner, MD, watched with concern. “I was like, ‘Angelina, when are you going to have your ovaries out?’ Because actually that’s a more scary problem.”

Kirschner, a gynecologic oncologist with NorthShore University HealthSystem, knows too well the risks of ovarian cancer. According to the American Cancer Society, the disease accounts for about 3 percent of cancers in women. Yet, it causes more deaths—140,000 per year—than other cancers impacting the reproductive system, according to the National Library of Medicine. It’s a disease for which there’s no screening tool, and symptoms can be subtle and easy to overlook.

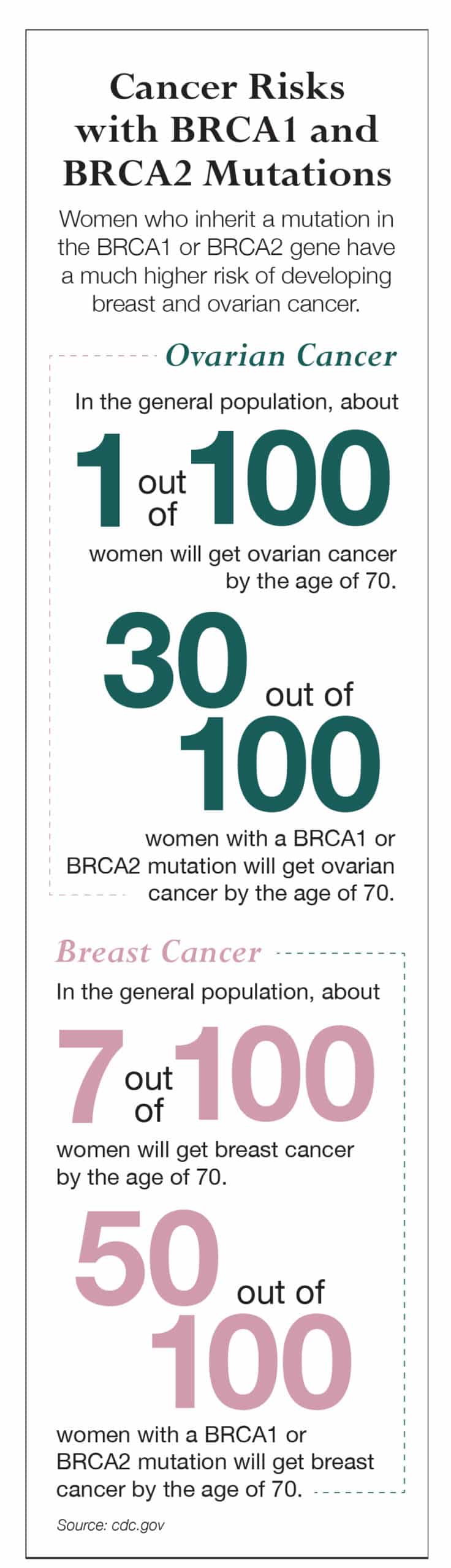

Jolie Pitt—who lost her mother, grandmother and aunt to cancer—has the BRCA1 gene mutation that increases the risk for cancer. Her doctors told her that she had an 87 percent risk of breast cancer and a 50 percent risk of ovarian cancer.

So when Jolie Pitt had her ovaries and fallopian tubes removed in 2015, Kirschner was relieved. “I was going to call her up or email her and just say, ‘Good job! I’m really glad you did that, I’ve been worried about you!’”

“[Ovarian cancer] is known as the silent killer because the symptoms are very vague. The symptoms mimic so many other things,” Kirschner says. Those symptoms can include bloating, a swollen belly, heartburn, an upset stomach and changes in urination (an increase in urgency or frequency) and usually happen after age 60. Often, women assume that the symptoms are related to menopause, Kirschner adds.

Kirschner recommends preventive ovary and fallopian tube removal surgery, called salpingo-oophorectomy, for anyone who has a BRCA mutation and has passed childbearing years. She also recommends that if a woman knows a BRCA mutation runs in the family, she should be tested to see if she has it. “If your mom has the gene, then you have a 50-50 chance of having the gene yourself. You should definitely consider testing,” Kirschner says.

One of the major challenges with ovarian cancer is that the symptoms usually don’t surface until the cancer has progressed, says Rajul Kothari, MD, a gynecologic oncologist with University of Illinois Hospital & Health Sciences System. “The hard part about it is that it’s usually detected in stage 3, which is when it’s already spread into the upper belly. And the symptoms that it causes are similar to the common stomach flu. It can cause nausea and vomiting. Women can feel bloated, can have changes in their bowel habits and can have decreased appetite,” Kothari says.

Kothari adds that when ovarian cancer is detected early on, it’s usually because a woman was seeking treatment for something else and an ultrasound picked up on the cancer.

Treatment for ovarian cancer almost always involves surgery and often includes chemotherapy. Surgery removes the ovaries and fallopian tubes, and the chemo helps eliminate fluid buildup in the abdomen and shrinks the disease. Kirschner says that a treatment called intraperitoneal chemotherapy, which involves giving the chemo directly into the abdomen, has been shown to be more effective and prolong survival rates. However, she says, many physicians steer away from that treatment, because it can have a particularly harsh effect on the body.

“It’s a very rough regimen. At NorthShore, we’ve had a lot of experience with intraperitoneal, and we have a prescribed way of giving it. [The patient needs] a lot of support—extra days just for IV fluids—to get through it. We have an aggressive antinausea regimen. It’s a huge time and financial investment for the patient to go this route, and some choose not to do that,” she says.

When it comes to ovarian cancer, surveillance is key, Kirschner says. If a woman has a BRCA mutation, she should see her doctor twice a year for an exam, an ultrasound and a CA-125 test, which is a blood test that can detect early signs of ovarian cancer. (The CA-125 test is not recommended for women with an average cancer risk because other conditions can cause a false positive.)

Kirschner says it’s also important to know your body. “Just be aware of changes and get a good primary care doctor who’s going to listen to you and be your ally in trying to take care of your health,” she says.

Originally published in the Spring 2016 print edition.

Kate Silver writes about health, travel and lifestyle for The Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, The Telegraph and other publications.