Pictured above: Daniel H. Angres, MD. Photo by James Foster

By Kate Silver

When Daniel H. Angres, 66, reads the headlines about the growing numbers of baby boomers addicted to—and overdosing on—prescription pain pills, he’s grateful that he found help for his own pill addiction 33 years ago. “I was sort of a product of the ’60s and ’70s; I kind of did all of the stuff many folks did during those days in terms of pot and alcohol,” Angres recalls. It wasn’t a problem, he says, until his late 20s or early 30s, when chronic pain led him to take painkillers, and he became addicted.

At the time, he was a psychiatrist interested in geriatric psychiatry. Recognizing his addiction, he quickly sought help and participated in an intense rehabilitation program. In fact, it’s that experience that steered his career to become a specialist on addiction, writing numerous books on the topic including Positive Sobriety.

“I think that my story is an example of gratitude for having been properly treated to save me a lifelong problem with addiction,” he says. “If I would have survived without treatment, which is questionable, and ongoing recovery, without a doubt I would be somewhere in those [baby boomer addiction] statistics,” he says.

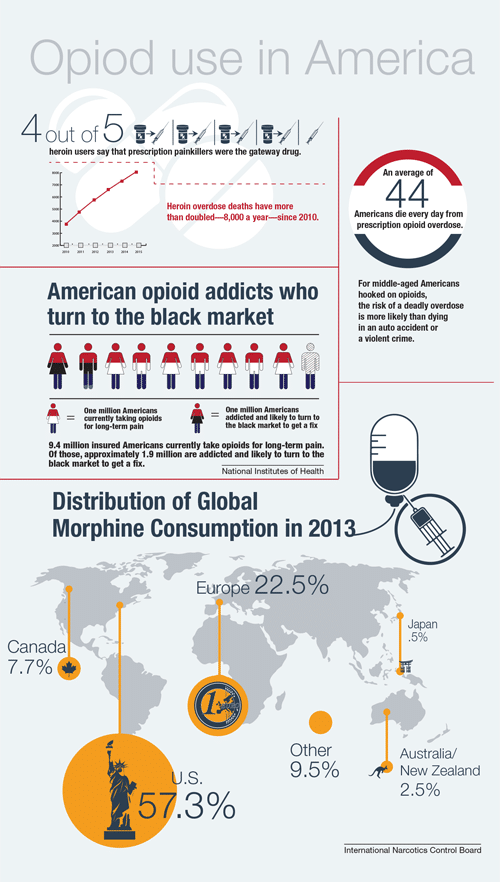

In March, The Wall Street Journal reported that the baby boomer generation, which numbers around 76 million Americans born between 1946 and 1964, is increasingly abusing drugs—particularly pain pills—and dying from overdoses.

According to the Journal, more than 12,000 baby boomers died of accidental overdoses involving prescription opioid pain relievers in 2013, out of about 16,000 total prescription opioid deaths for all ages. The total number of people dying from opioid overdose in 2013 is three times the amount of people who died in 2001 from the same cause, and, for the first time, the deaths in baby boomers exceeded that of those aged 25 to 44.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) found that in 2012–2013, an estimated 230,000 people in Illinois aged 26 and up used prescription pain relievers for nonmedical purposes, which is more than double the number—112,000—of 18- to 25- year-olds.

The CDC states that since 1999, Americans haven’t reported a difference in the pain they experience. And yet, the number of painkillers prescribed and sold in the country has nearly quadrupled. That, coupled with the known predilection of the baby boomer generation toward mind-altering substances, along with the generation’s aging and the natural pains that come along with it, sets the stage for a growing problem.

Angres, who serves as medical director with the Positive Sobriety Institute, chief medical officer with RiverMend Health and as an adjunct associate professor of psychiatry at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, says that to understand the problem, it’s important, first and foremost, that people understand that addiction is a disease. He says that 12 to 15 percent of the population, if exposed to addictive substances, will become addicted and, therefore, lose control over their use.

“There are different ways in which the reward center in the brain becomes vulnerable, and then people have a different, unique and more powerful reaction to addictive substances, including prescription drugs like hydrocodone, OxyContin, etc.,” he says.

Angres says that there’s a wide swath of people who fall into pain-pill addiction later in life. Some of them never had any problem with addiction or drugs previously and were prescribed painkillers that led to problems. Others may have partied in the ’60s and then didn’t have a problem with addiction until they were legitimately prescribed pain pills. Another group has continued using drugs since they were in their 20s, perhaps switching from one to the other along the way and, ultimately, discovering pain pills.

If there’s a history of addiction, Angres warns, people run a much higher risk of having an abuse problem with prescription drugs. That goes for him, too. A few years ago, Angres was scheduled for a shoulder replacement, and he was more worried about using pain pills than the surgery itself. He told his doctor and anesthesiologist about his concern, and then erred on the side of caution and took the minimum amount of pain pills, and only for a few days, which he asked his wife, who is a nurse practitioner, to hold for him.

“It’s serious stuff. If someone’s vulnerable or someone has a history, it’s life threatening if it’s not treated very seriously,” he says.

Gail Basch, MD, director of the Rush Addiction Medicine Program at Rush University Medical Center and assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry, says that 58 percent of opioid addictions began with the treatment of acute or chronic pain, and the risk of opioids far outweighs the benefits in chronic, noncancer-related pain. Problems can set in when a patient gets a feeling of stress relief or mood alteration from the pills, she says.

“There is a small percentage of people who describe a certain type of energizing, euphoric, stress-relieving response when they first take an opiate. And those are the folks I see in my office,” she says.

She adds that pain-pill addiction can lead to another danger: heroin use. As an opioid, the effects of heroin in the brain are similar to pain pills, and the drug is actually much more affordable on the streets in Chicago than illegally purchased OxyContin and other prescription painkillers. “Pain pills are expensive to purchase on the street. So oftentimes, people who are addicted actually switch to heroin for economic reasons. Heroin is cheap. That’s what we’re seeing here in Chicago, certainly. Heroin is $10 or less, a bag.”

Heroin is, in fact, the most common drug cited for substance-abuse treatment admissions in the state of Illinois and is the major opiate abused in Chicagoland, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). While NIDA states that new users tend to be young, white and suburban, it’s clear that an inexpensive market exists for those outside of that demographic.

To try to curb the problem, Basch says that physicians are being urged to talk more with their patients, prescribe in lower and limited quantities, check in more frequently with patients and consider nonopiate ways to relieve pain including anti-inflammatories, anticonvulsants and antidepressants. In addition to medications, physicians are using combinations of behavioral therapy, physical therapy and integrative techniques such as yoga, meditation, mindfulness and remembering simpler means of relief such as ice, elevation, and so on.

“Treatment for those struggling with opiate-use disorders is now available in your doctor’s office,” says Basch. In addition to methadone, which many are familiar with, there is buprenorphine, which suppresses withdrawal and relieves cravings, as well as naltrexone, which blocks the effects of opioids and offers relief and new hope for many.

In fact, those are three drugs that have been studied by specialists in the personalized medicine field—an area called pharmacogenomics, which uses genetics and technology to understand how an individual will potentially respond to a particular medication. By looking at a person’s DNA, someone like Mark Dunnenberger, PharmD, can predict which of those three medications (and some others) are likely to be more effective for an individual.

“Pharmacogenomics helps us peer into how a patient is likely to respond to a medication before we give them the medication, and we can at that point weigh cost/benefit, risk/reward and modify therapy as necessary,” says Dunnenberger, senior clinical specialist in pharmacogenomics with NorthShore Center for Personalized Medicine.

When it comes to pain medication and addiction, there’s still a lot to learn in the realm of personalized medicine, Dunnenberger says. But the type of work he’s doing gives physicians, like Angres, hope for tomorrow.

“That’s the future of so much of medicine, behavioral health and addiction. It’s such a critical area,” says Angres.

Pictured left: Mark Dunnenberger, PharmD. photo courtesy of Jonathan Hillenbrand, Media Production and Photography, NorthShore University Health System

Originally published in the Fall 2015 print edition