Technological developments are changing how we save lives and snub death

Fact checked by Jim Lacy

By all accounts, Gary Gibbon should be dead.

The 67-year-old had been living a full and healthy life in Santa Monica — a pulmonologist, allergist, and immunologist who enjoyed walking along the beach.

But in March 2023, he began losing weight unexpectedly. Then the cough started.

A Covid-19 test came back negative, but a chest x-ray revealed a large mass in his right lung. A biopsy of the mass led to the diagnosis: stage-3 squamous cell carcinoma. Lung cancer.

While Gibbon had smoked in the past, he had no family history of lung cancer. He consulted many colleagues to determine what could be done.

Within a few months, Gibbon, who had been doing chemotherapy and immunotherapy, ended up in the intensive care unit (ICU). The disease had advanced to irreversible pulmonary fibrosis. On the CT scan, his lungs looked like Swiss cheese — just connective tissues and holes. The lung cancer was holding on despite there not being much to hold on to.

As he prepared himself for palliative care, Gibbon remembered a Today Show segment his wife had mentioned a few months before. Two people with lung cancer had each undergone a revolutionary double-lung transplant. A year later, they remained cancer-free.

Gibbon hadn’t yet heard of a double-lung transplant and switched into research mode, which led him to the DREAM program at Northwestern Medicine.

“Maybe it was an option for me,” he says. Within a day, Gibbon was on the phone with the Northwestern team.

Still up for grabs

Ten years ago, Chicago Health reported on the state of organ transplantation. A lot has happened in the decade since. The changes, though incremental and slow, have also been groundbreaking.

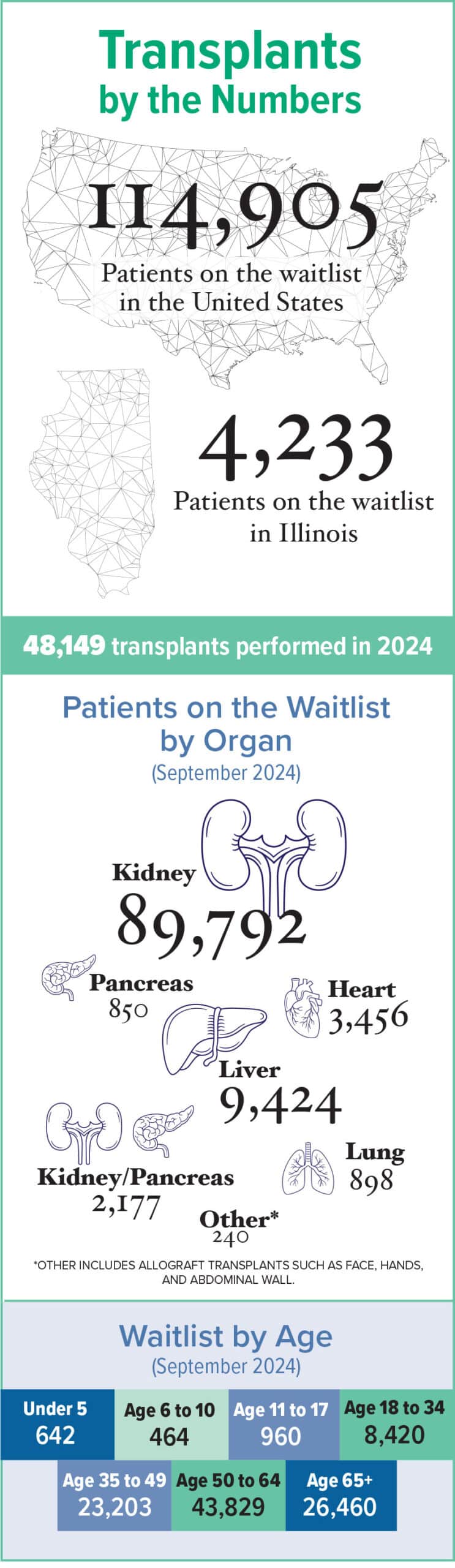

One big change is in the numbers. More people than ever underwent lifesaving transplants in 2024: more than 48,000, according to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. That’s a 3.3% increase from 2023, when surgeons performed about 46,000 transplants, and a 23.3% increase from 2020.

An increase in living and deceased donors helped make this possible, as did changes to the allocation system that the United Network for Organ Sharing manages. This improved access for traditionally marginalized communities.

Two of those marginalized communities — Black people and Latino people — have a far greater risk of developing kidney failure and requiring a kidney transplant, the most common organ transplant procedure conducted in the U.S.

Still, white people historically have benefitted from shorter wait times and comparatively better chances of getting on a waitlist. The rate of kidney transplants for Hispanic/Latino people increased by 6.5% from 2023 to 2024; the same procedure for Black people over the same period increased 1.5%.

Researchers in a recent JAMA study looked at data from more than 30,000 people with lung disease. Black people, they reported, were 39% less likely to undergo a lung transplant evaluation compared to white people. Income and location impacted care access, with people from under-resourced neighborhoods 97% more likely to die before undergoing a lung transplant. But Black individuals of all socioeconomic backgrounds experienced barriers.

Scientific hope in the era of technology

The last time Chicago Health spoke with Abba Zubair, MD, PhD, medical director at the Center for Regenerative Biotherapeutics at the Mayo Clinic in Florida, he talked about the fascinating work being done with human stem cells at the International Space Station (ISS).

Because of the decreased gravity in space, Zubair said at the time that stem cells can potentially grow faster. Scientists were testing just how quickly, and then how the cells would perform in clinical trials back on Earth.

“Stem cells can make tissues from all organs,” Zubair said back in 2015. “We haven’t figured out how to get the cells to grow specific to the organ, [but] if we can figure out how to differentiate, we can grow tissue.”

Zubair said then that we were still 10 to 15 years away from growing actual organs. When asked about this timeline now, Zubair says, “I feel like we’ll learn more in the next five years than we did in the last 10.”

Research takes time and builds off of all of the studies that came before it. “Clinical trials proved that it’s safe to use Earth-grown stem cells, which delays the progression of disease,” Zubair says. “What’s holding us up is the availability of funding.”

Time and opportunities to send stem cells to the ISS are other limiting factors. Once the cells are aboard the ISS, growth doesn’t happen immediately. The last batch of cells went up in 2017 and returnedin 2023. Considering all this, Zubair’s original timeline is still on track.

“There’s a good chance we’ll be growing organs in 2030 — not an organ that can go into people right away but beginning the clinical trials. I’m optimistic,” Zubair says. “It’s not a promise. It’s a scientific hope.”

Satish Nadig, MD, PhD, chief of abdominal transplant surgery and director of the Northwestern Medicine Comprehensive Transplant Center says this is the most exciting time to be in transplantation. “We’re on the cusp of the next era.”

Nadig’s passion comes through in conversation, especially as he talks about Northwestern Medicine’s accelerated surgery kidney transplantation program, which enables people to return home the next day.

Then there are the bold advances being made in xenotransplantation — the transferring of animal organs to humans. As of February 2025, four people in the U.S. had received genetically modified kidneys from pigs as part of a new clinical trial.

Animal organs open up many more potential donations, Nadig says, because 30% to 40% of donated human organs go unused; they’re simply not healthy enough to be transplanted. Still, the solution raises an ethical quandary. Critics object to cloning animals in order to grow organs for humans, yet pigs have been raised as food for thousands of years. Nearly 12 million hogs in the U.S. were slaughtered in January 2025 for food production.

While scientists explore that debate, the passion really picks up in Nadig’s voice when he talks about transplantation not just for organ failure, but to fight cancer. Which is why Gibbon wanted to speak with him.

Multi-organ transplant

The Double-Lung Replacement and Multidisciplinary Care (DREAM) program at Northwestern Medicine prioritizes people with advanced lung cancer who do not respond to conventional treatments. It was Gibbon’s only hope.

After Gibbon spoke with Nadig, as well as Ankit Bharat, MD, chief of thoracic surgery at Northwestern Medicine, he underwent tests to confirm he met the program’s requirements. The tests were not encouraging. His destroyed lungs were ideal for this kind of transplant, but his liver was riddled with cirrhosis from the cancer treatments.

“I was disappointed. This was my last chance,” Gibbon says.

Then, Nadig called Gibbon with good news: The team could transplant his liver, too. And not in two procedures, but all at once.

Gibbon says that physicians are taught to be suspicious of new treatments. Data is key, and all the data available so far on double-lung transplants were the two people on Today. Gibbon would be the first to undergo a single transplant procedure of two lungs, one liver — affectionately called the triple-L.

Six months after his diagnosis, Gibbon flew to Chicago to wait for a lung and liver donor. It took only 12 days for a donor to come through.

The team put in the new lungs following a cleaning and conditioning procedure that Bharat and his team developed during the pandemic. The entire triple-L procedure took just 10 hours.

Gibbon experienced something most patients with his dire diagnosis have not: coming back from the brink of certain death.

“It was a roller coaster,” Gibbon says. “Being a physician, I can be a scientist and look at the data, which I did. I knew my chance of survival was dismal. I had, maybe months. But I got this intense will to live — a spiritual drive to live — to not throw in the towel.”

Two years after the procedure, Gibbon is lung cancer-free. He takes walks, lifts low-level weights at the gym, and is looking forward to getting back to hiking once his immunosuppression treatments are less intense and he feels more confident.

And because the immunosuppressants, which keep his immune system from attacking the new organs, make him prone to infections, Gibbon only sees patients remotely.

Through it all, Gibbon gained a calling: advocacy. He talks regularly with people in support groups, battling myths about treatments, and he educates physicians about the triple-L program, which he describes as “breaking the shackles of the standard of care.”

In another decade, as organ allocation improves, if Zubair’s scientific hope of growing organs pays off, and if Nadig, Bhata, and others continue challenging norms, stories like Gibbon’s will become more common and save more lives.

Above photo: Ankit Bharat, MD and Satish Nadig, MD, PhD, perform a double lung and liver transplant on Gary Gibbon, MD. Courtesy of Northwestern Medicine

Originally published in the Spring/Summer 2025 print issue.

David Himmel is a Peter Lisagor Award winner and the former editor-in-chief of Chicago Health. He lives in Old Irving Park.