Heroin deaths are rising as state-funded treatment falls in Illinois

Nick Gore is sick. It’s like the flu, multiplied. His stomach is near eruption. Muscles and bones ache deeply. Tears stream down the 27-year-old’s face. He’s sneezing, dizzy, light-headed. Traffic on I-290 only makes it worse, as he drives the daily (or more) 30-mile trip from his mom’s house in Bartlett, Illinois, to Cicero Avenue and Lake Street on Chicago’s gritty West Side, looking for the white powder that will make him feel better. Searching for heroin.

He drives down an alley, and then another, until a kid on a corner spots him. It doesn’t take long. “They see a white kid in a somewhat decent car. [They know] you’re not there because you want to go get a gallon of milk,” Gore says.

He pays $10 for a bag, snorts some lines off a CD case, and it feels like he just got the biggest, warmest hug in the world.

The sickness goes away. He feels normal again.

So he heads back to the suburbs, back to his mom’s house, back to his job as a delivery driver for a paper company, sated.

For now.

“A few bad choices”

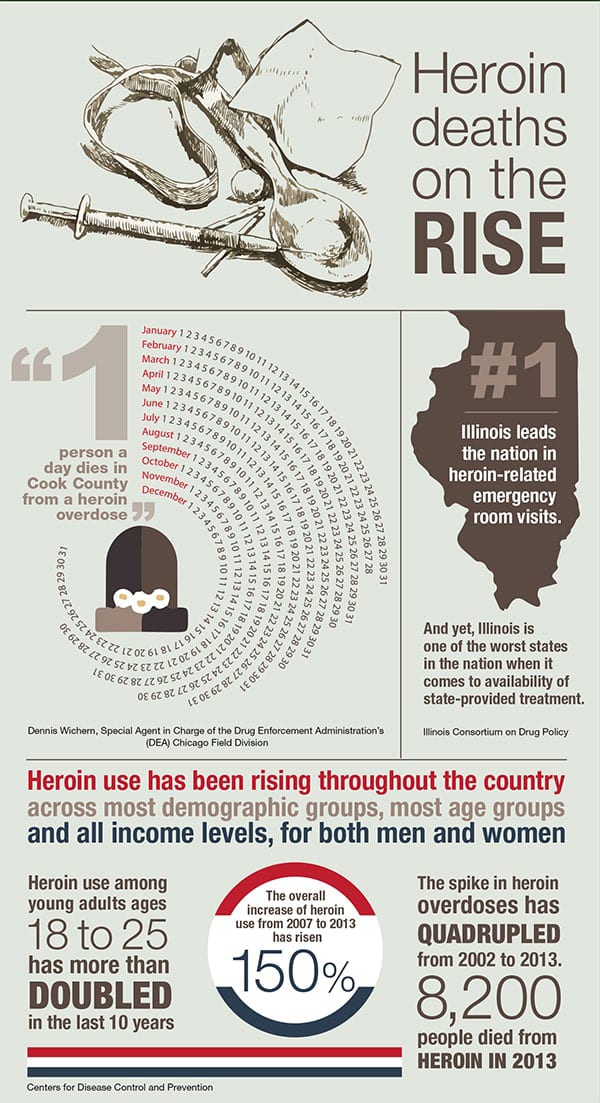

Once considered a drug largely used by urban populations, heroin use has been rising throughout the country across most demographic groups, most age groups and all income levels, for both men and women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The CDC has found that heroin use among young adults ages 18 to 25 has more than doubled in the past 10 years, and the overall increase of heroin use from 2007 to 2013 has risen nearly 150 percent. That rise has been accompanied by a spike in heroin overdoses, which have quadrupled from 2002 to 2013, when 8,200 people died from heroin, according to the CDC. Research shows that 45 percent of people using heroin are also addicted to opioid prescription painkillers, which are a part of the same class of drugs.

Illinois is a leader when it comes to heroin—and not in a good way. The Prairie State leads the nation in heroin-related emergency room visits, according to research by the Illinois Consortium on Drug Policy (ICDP) at Roosevelt University. From 2006 to 2012—the most recent statistics available—heroin was the most common drug, after alcohol, for which people enter publicly funded treatment (in 2000 it was No. 4 on the list). And yet, Illinois is one of the worst states in the nation when it comes to availability of state-provided treatment.

Gore fits the profile of the new wave of young, white users. His story illustrates how heroin addiction can happen to anyone including the boy next door. In high school, Gore was captain of his hockey team, made the honor roll, said please and thank you ma’am. He experimented a bit. He tried pot at 14 and didn’t like it, and he drank occasionally on the weekends with friends. He was a good kid with good parents and a good younger brother. His brother became a highly decorated U.S. Marine, while Gore went a different route. “I went on to become a highly decorated United States special force heroin addict,” he deadpans.

Gore laughs sardonically when he thinks back to the time in fifth grade when he won a competition for writing an antidrug essay for the D.A.R.E. (Drug Abuse Resistance Education) program and was asked to read those words in front of the entire school. Reflecting on how drastically opioids would go on to change him, he says, “There’s no discrimination in addiction. It doesn’t matter who you are or where you come from; it can infiltrate your home at any time with a few bad choices.”

His first encounter with opiates came in pill form. At 17, he broke his collarbone, and his doctor prescribed pain pills. That’s when he first felt a hint of that warm hug. But he wasn’t addicted then. That would happen when he turned 20 and developed a 19-millimeter kidney stone along with a number of smaller ones. He went through lithotripsy treatment, which uses ultrasound shockwaves to break up the stones. When the process wasn’t successful with one doctor, he’d move on to another one.

“The common denominator every time I saw one of those doctors was a little white pad with a prescription for narcotics,” Gore recalls. He says not one of those doctors cautioned him about the pills he was taking. Not one of them mentioned the word “addiction.” In the meantime, Gore went from taking 5 mg of Vicodin to 20 mg of OxyContin in a matter of months. In time, a doctor discovered that the root of the kidney stone problem was with Gore’s parathyroid glands, which control calcium, and they subsequently removed the glands.

When the pain was gone, a new problem curled into its place. After 12 months of taking prescribed opiates, Gore felt sick when he stopped. Beyond the withdrawal, he missed that warm feeling—that opioid hug. Missed it so much that he sought to get pills any way he could.

For the next five years, he stole pills out of friends’ medicine cabinets, bought them off the streets, faked injuries to get a prescription. He pawned his parents’ belongings to get money and went through a series of jobs, from outside sales to parking cars. Along the way, he says he checked himself into rehab multiple times, but he’d be back on the streets in five days, feeling lost and returning to the one thing that made him feel found.

He met a girl in rehab who had a history of heroin abuse. One day, when the two were driving around the city, the girl said, “This is where I used to go for heroin.” Next thing Gore knew, he’d made a purchase in an alley, and he was snorting his first line of heroin off a Tupac Shakur CD case.

“I was scratching so hard, I was bleeding because it makes you itchy, and I was throwing up profusely. And then I got a warm fuzzy feeling that I’d never had before. All those times I took those pills and had that warm fuzzy feeling, heroin just absolutely knocked it out of the ballpark. The fuzzy feeling was a million times better.”

The bag lasted a day and a half, but Gore was in. “Heroin has this unique way of stealing your soul and absolutely just hooking you.”

Every day, at least once a day, over the next 11 months, he’d get sick to his stomach. His body would ache. And he’d get back in his car and drive to the West Side. After the first few times, it wasn’t so much about feeling that warm embrace; it was about warding off the horrendous withdrawal symptoms—the aching muscles and bones, vomiting, diarrhea, watering eyes, ringing ears, dizziness. Misery. He’d go to just about any length to avoid that. “I burned every bridge that I had. I had no more family trust. I wasn’t invited to family functions any more. If I was invited, everyone’s purse was hidden,” he says.

He hated it. But he couldn’t stop.

A growing problem

Crisscrossed by railroads and sidled up to a river, Chicago has long been a hub for transporting goods, from the days of Potter Palmer and Montgomery Ward to its role today as a “home port” for heroin, in the words of Joaquin Guzman, aka El Chapo. That’s right, Mexico’s former drug kingpin, the head of the Sinaloa cartel had a pretty significant Chicago connection.

In 2010, the U.S. Department of Justice named Chicago the top stateside destination for heroin. Law enforcement officials say the majority of heroin, methamphetamine and cocaine in town comes from the Sinaloa cartel. According to Dennis Wichern, special agent in charge of the Drug Enforcement Administration’s (DEA) Chicago Field Division, heroin is the top priority for the DEA—and right now, it’s a scene that’s in flux.

Different organizations are getting stronger; some are getting moved out, so it’s always a kind of evolving game,” Wichern says. “It isn’t just a key five or ten people who control the heroin market in Chicago. There’s a whole bunch of them,” he says.

The DEA knows how heroin gets here, and officers know how it gets into the hands of people like Gore. It makes its way into town via I-55, usually hidden in a secret compartment in a tractor trailer. Then it’s stored in a warehouse or garage and doled out to a handful of distributors.

Wichern compares it to a management matrix: “You’ve got a CEO and then four vice presidents and eight groups below. It’s kind of the same way the drug-distribution outfits work. They’re fairly flat,” he says. “You might have four different levels, and then eventually it’s down to the gangs or nongang person that’s selling it right to the users on the street.”

On those streets, he says, the DEA is seeing a higher demand coming from younger, wealthier, suburban folks who have been abusing painkillers. They turn to heroin for a simple reason: price. “A hydrocodone tablet on the street might be $5 or $8, an oxycodone will be a little bit more. When they can no longer obtain the prescription painkillers, they’ll turn to heroin because it’s cheaper,” Wichern says.

A teener, which is a tenth of a gram, goes for $10.

Unlike buying painkillers, users have no idea what they’re getting when they purchase heroin—or any drug on the street for that matter. Heroin is cut with different additives or drugs. Wichern says he has seen it cut with everything from diphenhydramine, which is a sleep aid, to rat poison. Last fall, Chicago saw a rash of overdoses, with more than 100 overdoses in a matter of days because of heroin laced with acetyl fentanyl, a painkiller that Wichern says came from China and is 20 to 40 times stronger than morphine. The medical examiner’s office has not yet released toxicology studies indicating how many died from overdose. According to Wichern, two drug dealers have been arrested in association with the laced heroin.

“The addicts and the users all got to remember they’re risking their lives whenever they put an unknown substance into their bodies,” Wichern says.

One person a day dies in Cook County from a heroin overdose, Wichern says. Last year, 633 people in Illinois died from overdosing on heroin, up from 583 in 2013. Wichern is determined to stop that.

“Heroin’s still claiming too many lives, and way too many families are forever scarred and forever changed because of heroin abuse,” Wichern says.

He adds that those seeking help should call SAMHSA’s Treatment Locator at 800-662-HELP (4357) or visit it online at samhsa.gov/treatment/index.aspx.

A public health crisis

Jerrold Leikin, MD, has seen, firsthand, the spike in heroin use—and its dangerous aftermath—as the director of medical toxicology at NorthShore University HealthSystem and clinical professor at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine.

An overdose looks like this: “Essentially, [you] stop breathing. Everything shuts down, to put it bluntly. Your respiratory drive, your ability to breathe, your heart rate, your blood pressure; it all slows down in what we call central nervous system depression, which means the brain shuts down,” he says. “Within minutes.”

The solution is something called naloxone, a drug that can be injected or sprayed in the nose to counter the effects of opioids. Leikin says that by the time a patient has arrived, naloxone, also known as Narcan, has often already been administered by paramedics, and it works within seconds.

Naloxone is also distributed by a number of nonprofit organizations (one of the best known locally is the Chicago Recovery Alliance, a program that works with drug addicts and the HIV-positive community to reduce harm related to drugs). In recent years, police in DuPage and Lake counties have started carrying naloxone, and so have some departments in Cook County.

Leikin believes that in the future, naloxone will be as common as automated external defibrillators and EpiPens. At just $20 to $40 for a naloxone kit, it’s an inexpensive solution. In the hands of first responders, it has saved lives.

But with a drug as addictive as heroin, a brush with death often isn’t enough to stop users from going right back to the source. Addiction specialist Gregory Teas, MD, chief medical officer of Alexian Brothers Behavioral Health Hospital and medical director of Adventist GlenOaks Hospital Department of Psychiatry, says that heroin is the second most addictive drug there is—behind nicotine—when you look at the likelihood of becoming dependent after just one use. He says people can experience withdrawal symptoms after one or two doses of an opioid. “The dependency and rebound withdrawal can happen within days,” he says.

Teas says that, based on addiction research, about one in five Americans is vulnerable to addictive behaviors. “The way I look at it in my specialty […] about 10 percent of Americans have hard wiring for addictive behaviors. And another 10 percent have partial hard wiring, where they’re more at risk for abusing substances like the opioids,” he says.

He says that judging from his years of experience in the addiction field, if we were to give heroin to 100 people, about 30 of those people might feel an “unusually positive exotic high.”

He adds that they most often would want to try it again. But for the others, the experience can actually be quite negative.

“There are many people who use opioids who don’t like the feeling of opioids. They’re dysphoric; they make them anxious; they make them confused; many people get [nauseated],” he says.

In the detoxification unit, Teas has seen an upswing in people who started young. Namely, he’s seeing more users who began using painkillers in high school and then turned to heroin for a better high. “It’s so cheap nowadays that it’s very tempting for people to switch over to heroin from pain pills, because they’ll save money doing that,” he says.

Teas adds that the euphoria associated with heroin fades over time. After about four to six months, he says, heroin users aren’t using the drug for pleasure; they’re using it to avoid the sickness that comes from being sober. “What keeps people on heroin is not the high, it’s the withdrawal,” he says.

Medical treatment can take the edge off. The standard of care is often buprenorphine (also known as Suboxone), an opioid withdrawal agent and opioid maintenance agent that dissolves under the tongue and takes away the withdrawal symptoms almost instantly.

“In the old days, when we didn’t have buprenorphine, [patients] would literally be lying in bed for 72 hours and oftentimes vomiting, and just feeling miserable. Now they’re feeling comfortable; they’re attending groups.

If you observe someone 24 hours after admission for heroin dependency and saw them on buprenorphine, you’d say, ‘Gee, they look pretty good to me,’” Teas says.

Another treatment option is methadone, he says, which has been used since the 1960s to relieve withdrawal symptoms, reduce cravings and block the effects of opioids. Both buprenorphine and methadone are opiates and can be addictive.

Getting clean isn’t as simple as taking one medication. There are multiple drugs—known as comfort drugs—to help with withdrawal, Teas says. Clonidine, which is a blood pressure medication, affects brain centers that control withdrawal symptoms, and Gabapentin, which is an antiseizure agent, reduces the intensity of withdrawal. Some doctors will also prescribe sedatives to combat insomnia.

After about 10 days, patients get over most of the physical distress, but postacute withdrawal can last months longer, he says. It’s during that time that recovering addicts describe feelings of depression and anxiety. They want to get better, but they’re craving the emotional high—that warm embrace—they got from the drugs. That three- or four- month period, Teas says, is when most relapses occur—long after the standard 30-day rehabilitation program has ended.

The trials of treatment

Securing the help of the state when it comes to treatment can be a challenge in Illinois. In July 2015, the Illinois Consortium on Drug Policy at Roosevelt University released “Diminishing Capacity: The Heroin Crisis and Illinois Treatment in a National Perspective,” a report that found that Illinois’ treatment capacity fell more than any other state, tumbling 52 percent from 2007 to 2012, or 50 percent lower than the national rate. At the same time, the percentage of treatment admissions for the Chicago metropolitan area was more than double the national average, at 35.1 percent, compared to 16.4 percent nationally.

Illinois is the third worst state in the nation when it comes to providing treatment to heroin users, a drop from 28th just five years ago. Now, even as more people are becoming addicted to heroin (25 percent of state-funded treatment here is for heroin, compared to 16 percent across the nation), treatment capacity is disappearing, and only Texas and Tennessee show poorer numbers when it comes to providing publicly funded addiction treatment. The report also points out that Illinois is one of the few states where the Medicaid program doesn’t cover methadone and places limits on buprenorphine when it comes to treatment.

Kathie Kane-Willis, director of Roosevelt’s Illinois Consortium on Drug Policy and co-author of the report, says the outlook is grim. “I don’t know how we could possibly turn the corner on this,” she says. “Most states that have had low capacity are adding capacity—especially the states that are experiencing the same kinds of issues with the opioid and attendant heroin problem. And we’re not. No, we’re doing exactly the opposite of every state in the country.”

There is hope. The Heroin Crisis Act, authored by Representative Lou Lang (D-Skokie), passed into law in September. The bill allows pharmacies to dispense drugs like naloxone and requires first responders to carry the heroin antidote. It establishes education programs in schools, alters Medicaid to cover rehabilitation services including methadone, allows physicians to prescribe buprenorphine for more than a year (where it was previously capped) and will expand drug courts, aiming to keep users in treatment and out of jail.

Kane-Willis was ecstatic when the law passed. But she says there are still a lot of hurdles: It’s a far-reaching law that will be expensive to implement. “The backdrop for all of this is still the budget crisis,” Kane-Willis says.

“And I think it’s extremely difficult to move things along, when I think a lot of agencies, a lot of government, is a little stymied because there is no budget.”

Money is pretty hard to come by in Illinois these days, and addiction treatment has already been impacted. According to the Roosevelt University report, the proposed budget for fiscal year 2016 represents a 61 percent decrease from 2013 in Illinois-funded addiction treatment. Add in increased Medicaid funding, and it’s still a 28 percent cut.

“It’s going to take some time for these changes to come online and make a difference,” Kane-Willis says. The law has passed, she says, and now the real work must begin.

A long and winding road

Back in Bartlett, Nick Gore is a changed man. Now 32, it’s been more than three years since he snorted heroin. During a recent phone call, he explained that he alternates between talking excitedly about his latest opportunities—he met with U.S. Senator Dick Durbin to talk about tackling the heroin problem on a federal level and recently met with a major drug company to discuss what it can do to help combat opioid addiction—and recounting the dark times.

His addiction was an 11-month abscess, growing and pulsating with each line of dope. He was held up at gunpoint and robbed during a drug deal on the West Side; he spent time in the Cook County Jail for possession of heroin; he stole thousands of dollars from his employer to feed his habit; he alienated friends and family and went through multiple unsuccessful stints in rehab.

The abscess finally burst. His rock bottom was a failed suicide attempt, a cry for help in 2012, when he severed his own Achilles tendon with a butcher’s knife at his mother’s house. He was taken to a psych ward, where he spent five days in detox. Finally, something, somewhere, stuck. He moved into a sober house, began attending recovery meetings, and, slowly, the pain, the sickness, the insatiable physical need became more and more distant.

As his mind cleared, he found a new channel for his energy: He became a crusader against heroin. He signed on with the DuPage Chiefs of Police Association and has spent the last few years traveling around Chicagoland giving speeches about his experience, educating people in high schools, colleges, churches and other locations on the destructive force of heroin.

He’s testified before the legislature about the need for changes when it comes to painkiller prescriptions. And he’s met with doctors and dentists to share his story and discuss prescription-writing practices.

Recently, Gore took a job as an emergency services peer specialist with a pilot program called Project Connect at the DuPage County Health Department. In that position, he meets with heroin addicts who overdosed. He shares his story with them, guides them to helpful resources and, ultimately, shares hope for a better future. He reports, excitedly, that the program recently helped its first client enter treatment. It’s in these roles, he says, that he’s able to make sense of his own struggles.

“I’m grateful for every single thing that I went through, and I sincerely mean that. The only thing I wish I could change is the innocent bystanders that I hurt in the process. Family members, friends, co-workers, companies; that’s the only thing I wish I could change,” Gore says. “But if I didn’t go through everything I went through, I wouldn’t be the person I am today.”

Originally published in the Spring 2016 print edition.

Kate Silver writes about health, travel and lifestyle for The Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, The Telegraph and other publications.