Misconceptions abound of a debilitating disorder

Diana, 18, is a North Carolina high school senior who loves animals. She has six cats and a dog and is considering a career in animal care.

Yet in 2016, Diana found herself obsessed with thoughts that she would harm her pets. Even though she had never hurt them, she feared being around them in case this might occur. She stayed in bed for three months to prevent anything from happening, and she compulsively washed her body with household cleaners like Scrubbing Bubbles because she felt dirty and guilty. She also cut her arms to punish herself for her thoughts.

Diana has obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), a disorder that affects 1 in 100 children and 1 in 40 adults in America (about 2.3 percent of the population) at some point in their lives, according to the nonprofit Beyond OCD.

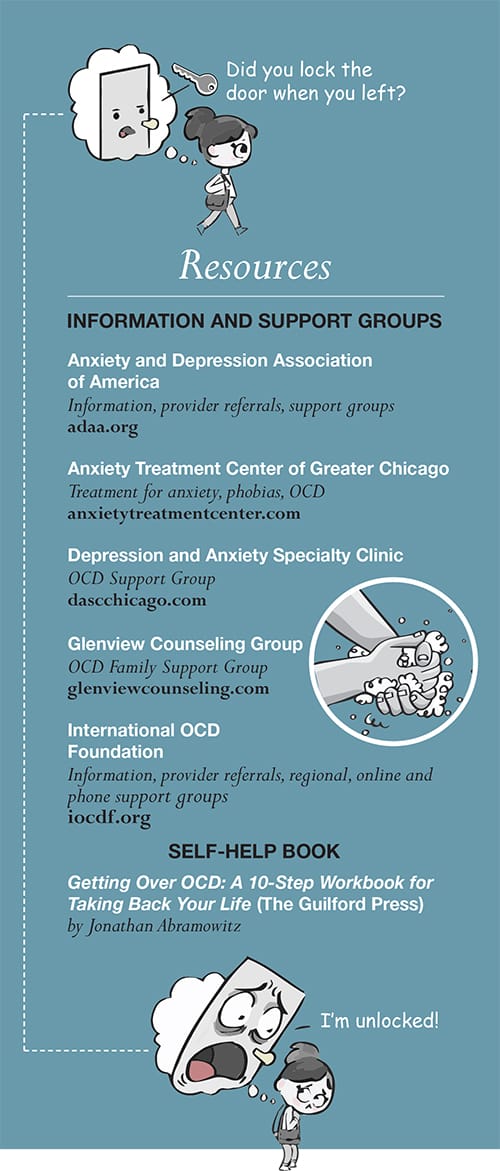

“OCD is seen as something funny, as kind of amusing and not that serious. Someone who has it is [considered] kind of quirky,” says Karen Cassiday, PhD, managing director of Anxiety Treatment Center of Greater Chicago, clinical director of Rogers Behavioral Health in Chicago, president of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America and chair of the scientific advisory board of Beyond OCD. Characters like the lead detective on TV’s Monk, whose OCD was presented as a character quirk, have contributed to this misconception, Cassiday says.

The term OCD is often used in a way that minimizes the condition, says therapist Michael Blumberg, LCPC, founder and director of the Glenview Counseling Group. People think OCD means “orderly or finicky or extra clean and neat,” says Blumberg, who has struggled with OCD himself. “People who don’t have OCD will say it as sort of a joke, ‘Oh, look at me, I’m so neat and orderly,’” and flippantly claim to have the disorder. “But that’s not what OCD really is,” Blumberg says.

These interpretations ignore the significant pain and despair the disorder can cause in the lives of those afflicted, Cassiday says. “It’s a very serious, debilitating problem with a lot of suffering.”

People with OCD experience intrusive, unwanted thoughts, images or urges—obsessions—that cause them anxiety. They then compulsively perform certain actions or rituals to help ease that anxiety. Sometimes these rituals are visible (like hand washing), though individuals can also have mental rituals (like needing to replace a “bad” thought with a “good” thought). OCD is diagnosed if these rituals become severe enough to disrupt a person’s daily life or cause severe distress.

Blumberg’s OCD symptoms included an intense fear of germs. He would wash his hands a dozen times a day, several minutes at a time, in very hot water, while rocking back and forth in prayer. He also counted things. (“There were good numbers and bad numbers,” he says.) And he had symmetry-based compulsions where he would have to set drink glasses down repeatedly or turn lights off and on until they felt “just right.” His OCD became so debilitating that he had to leave college for part of a semester as an undergraduate.

Many people with OCD have symptoms related to washing, cleaning and fear of contaminants, Cassiday says. But lesser-known varieties exist as well. Scrupulosity, for example, involves an excess concern over being morally or religiously correct. Fear of harming others is another.

What causes OCD? Desirée Wilkinson, PhD, a psychologist at the Chicago CBT Center, cites multiple factors, including genetics (though a single OCD gene hasn’t been identified) and environmental factors. One emerging theory holds that some sudden-onset cases in children might be caused by an immune response to a virus, Wilkinson says.

Though OCD is not considered curable, its symptoms can be reduced or eliminated, and people who have it can learn to manage their condition so it no longer disrupts their lives. The chief tool mental health practitioners use is a behavioral therapy called exposure response prevention (ERP), which involves gradual, structured exposure to the patient’s fear until the anxiety abates.

“Before this therapy was developed about 35 years ago,” Cassiday says, “[physicians] used to think OCD was one of the most severe, awful disorders, and they would resign you to living in a mental institution or being disabled.” But now, she says, OCD is considered “one of the most treatable disorders.”

Additional therapies used to enhance ERP include cognitive techniques to manage thoughts and mindfulness training to help people stay in the moment. New treatments being researched include attention control training and deep brain stimulation. But ERP is considered the most effective tool.

Blumberg used ERP along with medication to overcome his OCD about 14 years ago. Today this is the primary technique he uses to help his OCD patients.

Last year, Diana was treated with ERP at Rogers Behavioral Health. She brought one of her cats with her, holding it on her lap while visualizing her fears. “It’s really intense,” she says. “You are basically being exposed to your worst nightmares.”

But it worked. Now that treatment is finished, Diana says that while she still has intrusive thoughts, they bore her rather than cause her anxiety. “I’ve had these thoughts for so long that I’m just done with them.”