Illinois weighs psychedelic-assisted therapy in landmark CURE Act

Jean Lacy, with her mushroom-decorated button proclaiming “psilocybin saves lives,” has earned a reputation among clerks as the “magic mushroom lady.” In recent years, Lacy has made many trips to Springfield with other advocates to share their stories of healing through psychedelic-assisted therapy.

“For the longest time, I had the mentality that all drugs were bad and that they could ruin a person’s life if even touched,” says Lacy, pointing to influences like the DARE program and her family’s struggles with substance abuse.

After a traumatic childbirth, however, she turned to cannabis for relief. “I was at the end of my rope with what Western medicine had to offer me. It opened the door to a whole new relationship with what these substances could do when used in a therapeutic way,” Lacy says.

Today, Lacy is the founder and executive director of the Illinois Psychedelic Society, a nonprofit that educates and advocates for psychedelics and mental health. Its most ambitious undertaking: legalizing access to psychedelic-assisted therapies across the state.

The Compassionate Use and Research of Entheogens (CURE) Act is the first major effort to legalize clinical use of psilocybin — commonly known as magic mushrooms — in Illinois. Introduced in 2023, the legislation would establish a licensing system and advisory board to allow qualified practitioners to administer psilocybin for mental health treatment. While the bill has steadily gained support among lawmakers, deeply entrenched stigma and sensationalism remain significant hurdles.

Untapped potential for mental health treatment

Psilocybin, unlike lab-synthesized psychedelics such as LSD or DMT (which is both natural and synthetic), occurs naturally as an entheogen derived from certain mushrooms.

Researchers in the United States and Europe began investigating psychedelics in the 1950s and quickly recognized their therapeutic potential. Their studies were halted, however, following prohibition policies like the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. It has taken decades to rebuild research momentum, but recent findings highlight the promise of psychedelics coupled with therapy in treating many mental health conditions.

“You can put psychedelics under the category of non-specific amplifiers,” says Lindsay Brock Coulter, a trained psychedelic-assisted therapy provider. “They’re amplifying things inside of your mind, inside of your consciousness, inside of you.”

The result can be dramatic relief from treatment-resistant depression, substance use disorder, PTSD, and end-of-life distress. Each of these conditions involves deeply ingrained brain activity patterns that psychedelics may help rewire.

“It’s not necessarily the psychedelic that brings the healing,” says Jeanne Porges, a doctoral student in clinical psychology who leads her college’s chapter of Students for Sensible Drug Policy. “It’s the psychedelic that facilitates meaningful changes in thought patterns and behavioral patterns, and allows you to have the capacity to heal.”

Porges knows the power of these experiences firsthand. “In a lot of ways, psychedelics changed everything about my life,” she says. “Before I first tried mushrooms, I was in the hospital, I did not see a point in living, I did not see my value as a human being. Psychedelics brought all of that back for me. They brought self-love back.”

Establishing a regulatory framework

Unlike traditional medication, psychedelics are not a daily pill but typically a single guided experience that requires professional therapeutic oversight.

“You need to have somebody there who’s professional and to have it be in an environment where there are checks and balances,” says Coulter, who believes that decriminalization efforts must prioritize responsible access.

Sen. Rachel Ventura, 43rd District, who introduced the CURE Act in the Illinois Senate, agrees. “The medicine’s only half of the job. Otherwise, everyone who went to a rave and did a psychedelic in a nightclub would be healed,” she says.

The bill emphasizes structured care. Patients would be required to attend three sessions with a trained professional — one on the day of treatment and two follow-ups. Integration is the therapeutic process of helping patients rebuild neural pathways and apply insights gained from the psychedelic experience.

“I want to make sure people understand the importance of having a structure,” Ventura says. “Legislation like this is needed to create some type of guardrails, to make sure that people who are utilizing this medicine have a good experience.”

Meeting mental health needs

In Illinois, the need for effective mental health treatment is pressing.

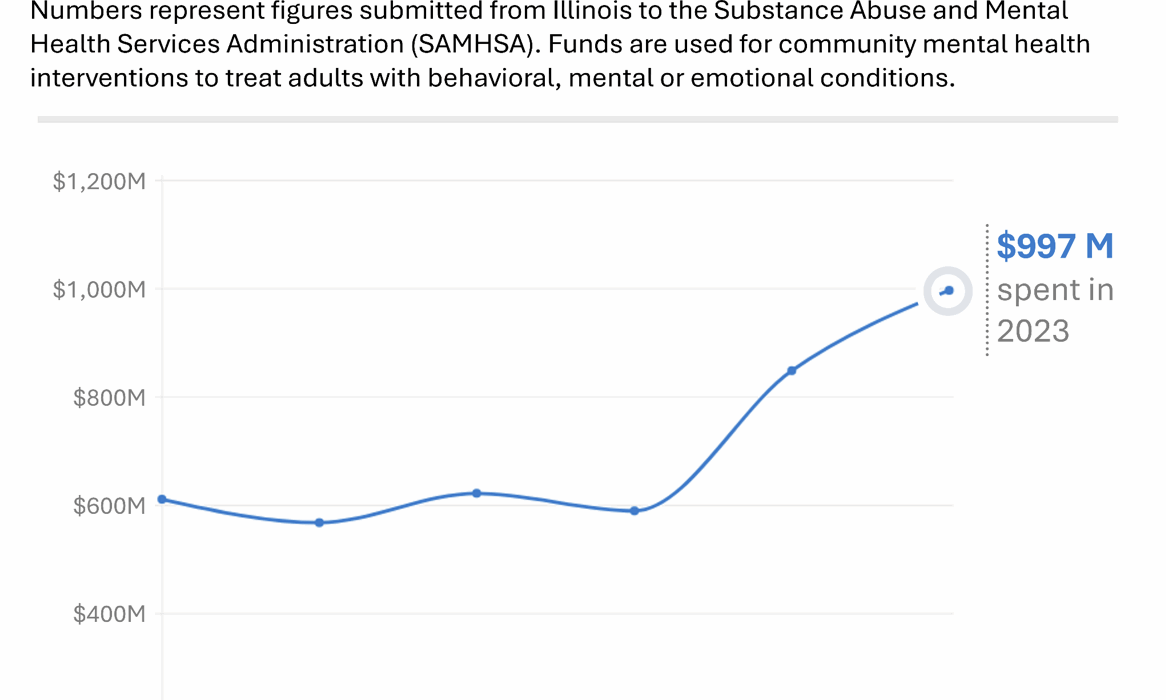

According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Illinois mental health agencies spent nearly $1 billion in 2023 — a figure that has been steadily increasing.

The toll is not only financial. According to the Illinois Department of Public Health, suicide rates in the state have climbed since the Covid-19 pandemic, with more than 1,500 deaths in 2022, the most recent data available.

Law enforcement officers face disproportionately high rates of mental health struggles. Dave Franco, a former Chicago Police Department officer who worked in narcotics for decades, says psilocybin was virtually invisible in his career — “exactly zero” arrests for entheogens in 31 years. Yet he believes it can play a crucial role for first responders moving forward.

“The long game for me is, I know three police officers personally who committed suicide,” Franco says. “I’m hoping that if they lift the federal restriction on psychedelics, and police officers can go to these clinics and get the help they need, it will make them better people and prevent suicide.”

The legislative push

The potential benefit for veterans and police officers — groups that have been central to psychedelic-assisted therapy research — has helped the CURE Act gain bipartisan interest.

“The biggest hurdle, I would say, is getting over the partisan line,” Ventura says. “From the Republican caucus a lot of their concern was about the legalization of drugs and the message that’s being sent.”

But educational outreach has shifted minds. Ventura says some colleagues who have never heard of psilocybin have since become supporters. The CURE Act has even gained a Republican co-sponsor in Senator Craig Wilcox, a military veteran.

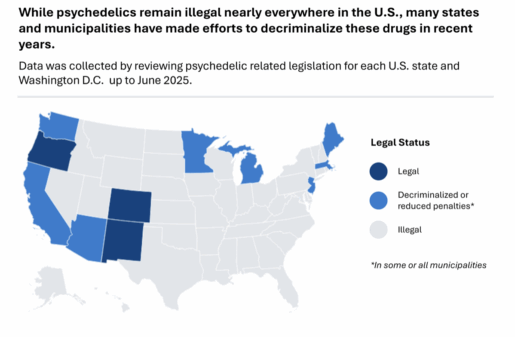

Illinois is not alone in pursuing clinical access. Since 2020, lawmakers in nearly 75% of U.S. states have introduced bills to legalize psychedelics, with about half still pending. Like the CURE Act, many focus on licensed medical use and oversight systems.

Some of these efforts have come within inches of success. Bills in California and Arizona advanced to the governor’s desk before being vetoed; while Colorado, Oregon, and New Mexico have decriminalized or legalized psilocybin to varying degrees. In April 2025, New Mexico’s governor signed the Medical Psilocybin Act into law. Similar to the CURE Act, the measure establishes a framework for licensed therapy providers to treat qualifying medical conditions.

Advocates like Lacy hope Illinois will be the next breakthrough state, propelled by personal stories of psychedelic healing. “I cannot understate the impact of people sharing their stories,” she says. “We need more of this.”

That outreach has already gained traction. According to Ventura, the CURE Act is close to securing the 30 Senate votes needed for passage. From there, the fate of psilocybin policy in Illinois will rest in the House and ultimately with Governor J.B. Pritzker.