Treatments can help the stabbing pain of plantar fasciitis

It had been a few weeks since Cathy Joyce had completed her first marathon.

The 51-year-old North Center resident, who has been running since her college days, felt a sharp pain in the bottom of her foot as she was trying to get out of bed.

“It took me by surprise,” she says.

“I didn’t know what it was. I thought it was a random weird thing, but then I mentioned to someone that I had this terrible pain on the bottom of my foot, mostly my heel.”

Katie Fischer, 35, who lives in Old Town, had a similar experience several months after she completed her second Ironman triathlon. When she got out of bed one morning during her offseason training, her feet ached and her calf muscles were tight. As the day progressed, she began to loosen up and the pain went away. But eventually the pain returned — with a vengeance.

In both cases, these Chicagoans had plantar fasciitis, a common foot problem that can afflict runners, hikers and nearly anyone who does a lot of walking or standing without many breaks — cashiers, individuals in the healthcare industry, people who work in warehouses, teachers. It even affects competitive dancers and people in marching bands, says Katherine Dux, DPM, a podiatric surgery specialist at Loyola Medicine. Other culprits include being overweight, which can increase stress and strain through the arch of the foot, and a lack of adequate support and cushioning in shoes.

The stabbing pain can seemingly come from out of nowhere and typically happens when a thick band of tissue — known as the plantar fascia, which supports the arch in your foot and extends from your Achilles’ heel to your toes — becomes inflamed.

For some, it can be treated very quickly. For others, the problem can drag on for years, becoming a long-term debilitating issue.

Stretching and modifying activities

While it may seem like a heel problem, other parts of the body are involved with plantar fasciitis too. Treatments start simple, with stretches and non-invasive techniques, and take the whole body into account.

“We often think it’s just one thing, that it’s just in your foot. But your whole body is connected, and it can cause problems radiating up to your knees, hips and glutes,” Fischer says.

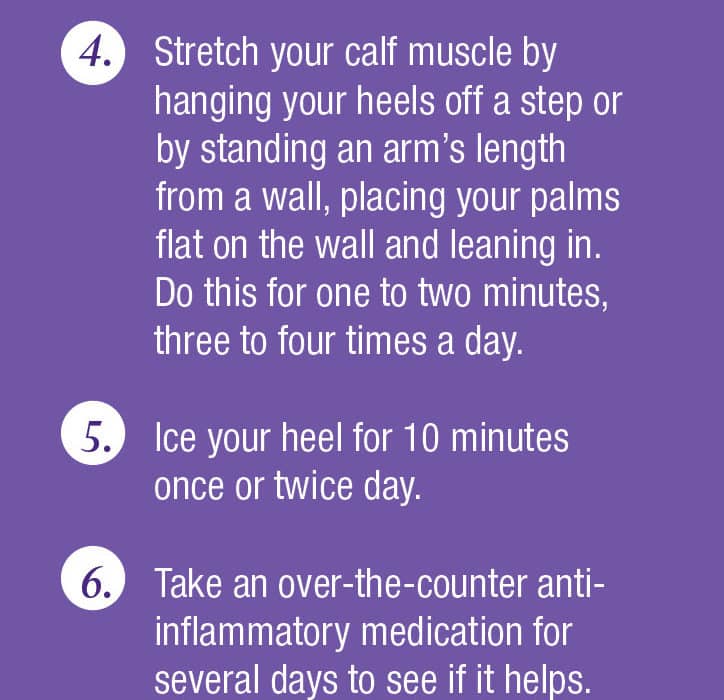

Many people don’t realize that plantar fasciitis is associated with having a tight calf, says Kelly Hynes, MD, assistant professor of orthopedic surgery at UChicago Medicine. Stretches can help, she says, such as a runner’s calf stretch or yoga poses that stretch out the lower extremities.

Other tips are to freeze a water bottle and roll it under your foot to help with inflammation, Hynes says, or to use a foam roller under your calf. Both can hit trigger points and break up the adhesions and inflammation in the fascia — the fibrous connective tissue that runs throughout your body — in your calf and foot. Physical therapy can help, too.

Your whole body is connected, and it can cause problems radiating up to your knees, hips and glutes.”

Similarly, the Graston Technique uses a metal instrument to apply targeted pressure to the plantar fascia. It helps break up adhesions in the fascia, improve circulation to the area and elongate the muscle fibers.

Wearing appropriate shoes is important, says Lowell Weil Jr., DPM, CEO of Weil Foot & Ankle Institute. Walking barefoot or wearing flimsy flip-flops can create problems from a lack of support. Both Weil and Hynes recommend wearing a shoe that offers at least an inch of support in the cushioning at the bottom of the shoe; Weil recommends 1 to 2½ inches.

If you’re overweight or obese, it helps to slim down since extra weight increases the pressure on plantar fascia ligaments and puts you at greater risk for problems.

Typically, if you’re actively stretching and modifying your activity, you’ll start to see improvement after four to six weeks, says Dux, who usually recommends athletes take a month off from their activity to treat the pain.

Alternative treatments

If plantar fasciitis doesn’t respond to stretching and conservative treatment, specialists can try other measures.

Depending on the patient, Dux, Weil and Hynes recommend wearing a night splint because it keeps your foot in a stretched position while you sleep “so things aren’t as tight in the morning, which is often the worst time for plantar fasciitis pain,” Hynes says.

For severe cases, in which a patient is walking with a limp, Dux will suggest patients wear a walking boot.

Weil and Hynes also recommend using extracorporeal shock wave therapy, where short bursts of sound waves are used to penetrate the body and break up scar tissue. Patients can see results in six weeks, they say.

If none of those remedies work, there are other more controversial options. Some seek surgery, but Dux says surgery is not guaranteed to resolve heel pain. Steroid injections aren’t usually recommended either because they only reduce the inflammation and don’t help the tissue to heal, Dux says. “And there could be inherent risks with using steroid injections,” she adds.

Some people with chronic plantar fasciitis turn to placenta injections, which involve injecting amniotic fluid and granulized amniotic membrane — dehydrated, crushed-up placenta that is sterilized, turned into a powder and rehydrated — into one’s foot. The injection is done in the bottom of the heel into the ligament in the plantar fascia.

For the past year and a half, Weil has been using placenta injections and he’s seeing results. So is Dux. Researchers speculate that molecules in the amniotic fluid may help reduce inflammation by sending cells to the plantar fascia to improve healing in the area.

“Placenta injections are extremely strong anti-inflammatories and help tissue regeneration,” Weil explains. “With chronic plantar fascia problems, the tissue becomes scarred and irregular. The injection itself can cause a biological response and then help reorganize the tissue into more normal tissue.”

Still, further research is needed on the use of dehydrated amniotic membrane treatments for plantar fasciitis, Dux says.

“It’s a somewhat controversial treatment given the fact that some literature suggests it is helpful and other literature hasn’t found significant support for treatments,” she notes. But, she adds, “[Doctors] use it for many soft tissue injuries. They use it in sports medicine in all areas of the body to help facilitate healing.”

Regardless of the type of treatment you choose, it’s important to be proactive. Not doing anything doesn’t usually work. Many people don’t realize the available treatment options — from stretching to shock wave therapy — that can help them put their best foot forward.