Where cardiology and sleep medicine meet — and how they impact each other

Fact checked by Jim Lacy

Dana Huelat’s husband and kids noticed something about her sleep last summer: Her snoring and breathing pauses seemed worse. She made an appointment with her primary care physician, who suggested testing for sleep apnea, which causes repeated interruptions in breathing during sleep; the disorder also is linked to heart disease.

“I mentioned that I had struggled with being exhausted for a very long time without any relief from lifestyle changes, getting my hypothyroid number in check, and even when I slept seven or eight hours,” Huelat says.

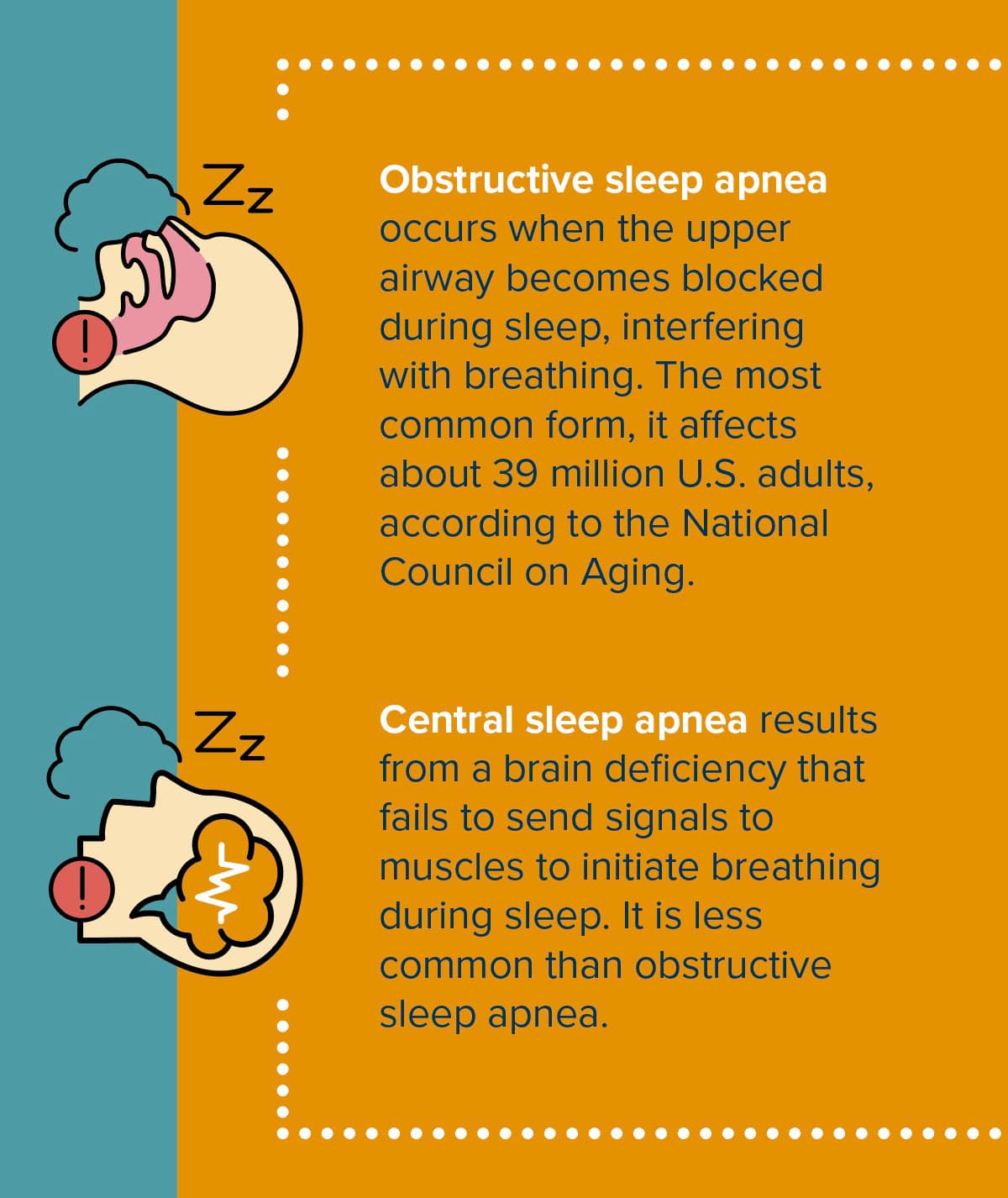

After undergoing sleep tests, she was diagnosed with complex (or mixed) sleep apnea, which is a combination of obstructive sleep apnea and central sleep apnea.

“I am concerned that the undiagnosed years have had effects on my mind and body, which is why I am in the process of seeing a cardiologist and a neurologist,” she says.

The connection between sleep apnea and heart health

Sleep apnea is associated with cardiovascular conditions because the condition keeps people from getting rest while they sleep and instead exposes them to stress, says Moeen Saleem, MD, electrophysiologist at Midwest Cardiovascular Institute.

With central sleep apnea, if a person is not taking a breath, their oxygen levels go down, which is like being mildly suffocated, Saleem says. “This triggers the fight-or-flight stress response. The body makes adrenaline, which can raise heart rate, blood pressure, and cause constriction of the arteries and vessels throughout the body, which adds to risk of other cardiac or neurologic events.”

Additionally, poor sleep contributes to unhealthy habits that can hurt the heart, such as higher stress levels, unhealthy food choices, and less motivation to be active, says Mark Rabbat, MD, cardiologist at Loyola University Medical Center and professor of medicine and radiology.

Traditional care models should absolutely consider the link between conditions such as atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and heart failure with sleep disorders, Rabbat says. “Research strongly indicates a significant association between them.”

Central sleep apnea treatment innovations

Often, a person is diagnosed with sleep apnea after a sleep study. Based on results, a sleep physician will suggest treatment options. Obstructive sleep apnea is commonly treated with a CPAP machine, which requires wearing a mask at night. When the person inhales, the mask delivers oxygen with some pressure to open up areas of obstruction.

Huelat began using a CPAP machine shortly after her diagnosis. She says she feels reassured that science has proven it to significantly decrease future episodes and help heal affected parts of the brain. “It admittedly isn’t the easiest or most comfortable thing to sleep with, but the benefits outweigh the time it will take to get used to wearing one,” she says.

However, since Huelat has mixed sleep apnea, she isn’t yet sure how doctors will treat her central sleep apnea. Because people with central sleep apnea don’t initiate regular breaths, wearing a CPAP doesn’t address that issue.

A therapy called adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) might be helpful in some cases, Saleem says. “It is a hybrid in a sense. It’s like a CPAP machine where if a patient initiates a breath, it will deliver positive pressure, and if a patient fails to take a breath, it will detect it and deliver a breath, all done through a mask.”

ASV, however, is not recommended for people with heart failure. For those patients, Saleem says the Remedē System is currently the best option. Implanted into the chest, the device stimulates a nerve that sends signals to the diaphragm to stimulate breathing.

“It activates automatically and restores a more normal breathing pattern so that you can treat your central sleep apnea without a mask or medications,” Rabbat says.

The FDA evaluated data from 141 patients to assess the effectiveness of Remedē in reducing apnea hypopnea index (AHI) — a measure of the frequency and severity of breathing pauses. After six months, half of patients with an active Remedē System implanted showed their AHI reduced by 50% compared to a reduction of 11% in people without the device.

Surgery to implant Remedē takes less than two hours and patients go home the same day. “Overall, it’s a safe procedure. The risk of anything dangerous or life threatening is less than 1%,” Saleem says.

As Huelat navigates her treatment options, she says she will consider Remedē if her doctors recommend it.

“I have horrible short-term memory and frequent brain fatigue, which I hope treatment can improve. I also have weight I haven’t been able to lose,” she says.

She’s most excited, though, about a positive change in her relationships. “I want to stay up and watch movies with my husband and kids. I want to say ‘yes’ to a late dinner. I want to have more to give to myself, family, and friends,” she says. With time and the right treatment, those dreams may come true.

Originally published in the Spring/Summer 2025 print issue.

Cathy Cassata specializes in health, mental health, and human behavior. She connects with readers in an insightful and engaging way.