A unique view of Chicago’s International Museum of Surgical Science, at the crossroads of art, history, and medicine

Fact checked by Catherine Gianaro

Spanish priest and surgeon Miguel Servetus published in 1553 a groundbreaking book describing how blood flows through the heart and lungs. Today, this process — pulmonary circulation — is a basic tenet of medicine. But at the time, city officials in Servetus’ town accused him of heresy. They sentenced him to be burned alive, along with all copies of his book. Three copies, however, survived, and he is recognized today as the first person to correctly describe pulmonary circulation.

Servetus’ tragic story is one of many historic tales that unfold within the four floors of Chicago’s International Museum of Surgical Science, alongside paintings, artifacts, and more. The stately 1524 N. Lake Shore Drive greystone mansion was built in 1917 and is one of the Seven Houses historical district on Lake Shore Drive.

“You can’t really see what it is until you come here,” says Michelle Rinard, manager of exhibitions and development. “Medical history is not a straight line of progress. It’s important to show the medical missteps in history to get to where we are today.”

At the museum, visitors can view amputation saws, trepanned skulls, a large jar full of old kidney stones, and more. But this museum is no tribute to trauma. Instead, it is an eclectic homage to Chicago’s myriad contributions to medicine— a city that spawned such giants as Abbott, Blue Cross Blue Shield, Provident Hospital, the first Black nursing school, the American College of Surgeons, and the International College of Surgeons (ICS).

The man behind the museum

Thorek proceeded to assemble a collection of artifacts, paintings, manuscripts, sculptures, and books from surgeons, collectors, and sections of the college. Besides its contents, the mansion itself is a masterpiece: Architect Howard Van Doren Shaw designed it along the historic lines of Le Petit Trianon, a French chateau on the grounds of Versailles by architect Ange-Jacques Gabriel. That building was gifted to Marie Antoinette and is today a museum as well.

“Max Thorek was a really influential person, collector, artist, and musician. He had the vision of creating the museum through art,” Rinard says. The narrative visual interpretations make the dense subjects easier to digest.

The museum’s mission is to celebrate international surgeons’ work. One of the permanent exhibits, Taiwan Hall of Fame, showcases the country’s combination of traditional herbal medicine, folk remedies, and Western medical technology.

The museum feels like a time machine — no sterile labs or laparoscopic surgery here. It’s hard not to imagine what it was like to live in the four-floor mansion, to descend the marble staircase, to hear what Lake Shore Drive traffic sounded 100 years ago, to pull your volumes off the shelves in the library, or to host a party by the fireplace in the Hall of Immortals (currently filled with 12 large sculptures of medical innovators).

“When you learn about these figures, you see that surgery used to be so brutal and painful. Doctors didn’t yet understand the human body and human anatomy,” Rinard says.

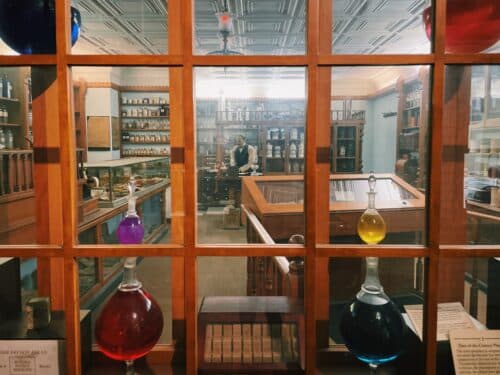

The “Pick Your Poison” exhibit showcases some of our most potent drugs, from medical miracles to social menace. Items like advertisements for cocaine toothache drops often spark conversations about prescription drugs and how we use them today, a contemplation of what has and hasn’t changed in the past 100 years.

“I didn’t know before coming here how far we’ve come in medicine,” says Rinard, who has worked at the museum for nearly a decade. “You don’t think about it, because you’re living in the present. But here you learn about surgery and medicine through art — painting and sculpture.”

Incorporating artists

In addition to its regular exhibits, the museum dedicates galleries to contemporary artists like Jose Luis Benavides, a local video artist, photographer, and adjunct professor at City Colleges of Chicago. Benavides’ Letters to Lost Loved Ones highlights the medical treatment of incarcerated people in Illinois during the Covid-19 pandemic.

In 2020, museum organizers planned an exhibit around nurses who practice art — painting, fabric arts, poetry — but their collective works evolved into a reflection on Covid-19. The following year, the museum hosted an exhibit dedicated to nurses lost during the pandemic.

Artists-in-residence at the museum have access to the museum’s archive and collections, as well as space to hold exhibits. Chicago-based artist Cheri Lee Charlton’s illustrations, for example, explore medicine through the lens of how it has historically and repeatedly misdiagnosed and failed women.

Museum administrators also launched a series of events, including a speed-friending event, designed to introduce new acquaintances to one another with the museum as backdrop. The series has been popular and is ongoing.

Just as it was in its early years, the mansion continues to be a social hub to exchange ideas, appreciate the past, and learn about Chicago’s place in medicine.

Photography and additional reporting by Katie Scarlett Brandt

Claire Zulkey lives in Evanston. Her health stories have also appeared in Chicago Health, the New York Times, the Atlantic and Runner’s World.