Conversation starters and strategies to guide young people toward treatment

If opioids hijack your teenager, keeping them safe while they use can be the buoy that saves them.

Telling a teen in the throes of an opioid addiction to just stop or say no won’t work once cravings, withdrawal, and other elements of addiction have taken root.

“If you alienate someone before they’ve even engaged in treatment, you may never have the chance to help treat a substance use disorder,” says Maria Rahmandar, MD, medical director of the substance use and prevention program at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. “Recovery and treatment is really a continuum. It’s not all or nothing.”

Highly addictive, opioids come in the form of prescription pain relief pills such as Vicodin, and street drugs, like heroin. Overdose deaths among U.S. adolescents aged 14 to 18 nearly doubled in 2020 compared to 2010 and increased another 20% during the first half of 2021, according to UCLA Health.

Yet, substance use among this demographic remained fairly unchanged during the same time period. Researchers traced the cause to counterfeit street drugs laced with fentanyl. The synthetic opioid is 50 times more potent than heroin and 100 times more potent than morphine, making it highly lethal.

Rahmandar recalls one patient whose parents took a harm-reduction approach to addiction. Because they knew their child was using heroin, the parents attended a 15-minute training on how to administer naloxone — a Food and Drug Administration-approved medication for reversing opioid overdose. They kept the medication in the house for emergencies.

After finding their child unconscious from an overdose, the parents administered naloxone, saving the teen’s life. Rahmandar then established healthy coping tools to help the teen fight cravings and battle negative emotions — positive changes to help the child reach their goals.

Small steps to recovery

While some addiction treatment approaches go for all-or-nothing, harm reduction focuses on keeping teens alive as they continue to work on their drug use.

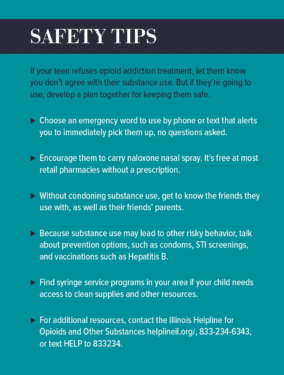

“Harm reduction is the idea that there’s a lot of positive changes and healthy changes you can make between using all the substances and not using anything,” Rahmandar says. “That can be decreasing use; not using alone; carrying a naloxone overdose reversal medication; and using fentanyl test strips to check for fentanyl in your drug supply.”

In the process, you build trust and guide teens to treatment, whether that involves taking medications, speaking to a therapist, going to SMART Recovery or Narcotics Anonymous groups, or entering a partial hospital or residential substance use treatment program.

Teenage brains are still developing, which makes them particularly susceptible to becoming hooked on drugs, including marijuana, opioids, and other substances, says Anoop Vermani, MD, child and adolescent psychiatrist with Rogers Behavioral Health in Hinsdale.

Substance use causes a host of problems for teens, including isolation, falling grades, sleeping problems, irritability, and less time with family and extracurricular activities, Vermani says.

When all signs point to substance use, Vermani advises having a frank discussion with your teen. Start the conversation with open-ended questions: “I’ve noticed you’ve been sleeping more. Your grades aren’t good. What’s going on?” Straightforward inquiries, which come across as accusatory, will shut the teen down.

Give them time to talk. Ask if any of their friends are using drugs. This will let you segue into asking whether your teen is using any substances. If they are, try to find out what made them start. Are they trying to manage anxiety or depression? Do they want to fit in with a certain person or group?

“People struggling with substance use are only thinking about the positive effects rather than negative consequences,” Vermani says. “Let them explain how the drugs are helping them before asking, ‘Have you noticed any harm from your use?’ It helps teens recognize how their substance use has been a problem.”

Remove barriers to treatment

Vermani describes the euphoric effect opioids have on the brain. “They start making choices that place their opioid use above all other decisions. That’s what makes this drug so dangerous.”

To minimize stigma, Rahmandar recommends considering the teen as a person with a substance use disorder rather than an addict. Refrain from referring to them or their urine as dirty or clean. Instead, the urine has substances in it.

Even though it’s difficult to see past the present day’s struggles, Rahmandar urges parents not to lose hope. Teens can get better, make positive changes, mend relationships, and lead happy, productive lives. But they need support.

Originally published in the Spring/Summer 2023 print issue.

Melanie Kalmar is a journalist specializing in business, healthcare, human interest, and real estate. When not writing, she enjoys spending time with family.