When treating stroke, every minute counts. Local hospitals are speeding up access

Andy Streiter, 49, a Chicago executive and father of three, always starts his day off with a ride on his Peloton bike. One August day in 2020, he did his usual ride. “I felt good. It was a good ride,” he recalls. Then he headed upstairs to retrieve a package from the porch. Suddenly, the left side of his body went numb, and he couldn’t hold the door open.

His wife heard the door slam and wandered in to find Streiter face down on the couch. “I was going in and out the entire time,” Streiter recalls. He couldn’t get up or make half his body move. “I’m calling 911,” his wife shouted.

Luckily, the Streiters live close to a hospital, so it was a short ride to the emergency room (ER). “In the ambulance, they told me I was stroking out,” Streiter says. “But they had technology in place and had individuals in the ER, all prepared for whatever needed to happen.”

Streiter was one of the lucky ones. Thanks to his wife’s quick action and a highly coordinated effort at NorthShore University HealthSystem, he was able to get lifesaving treatment within 15 minutes. He had his stroke on a Thursday and walked out of the hospital two days later. By Monday, he was back at his desk, working as an executive vice president at a recruiting firm.

Each year, 795,000 people in the U.S. have a stroke, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As Streiter’s story shows, with stroke care, timing is everything. Medical centers are constantly trying to reduce their “door to needle” time — in other words, the time it takes from entering the ER to the moment the patient receives the clot-busting drug, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA).

The lifesaving drug must be administered within three hours of symptom onset. After this three-hour window, it’s more likely that a patient will lose function, need rehab, and possibly lose the ability to work and live independently.

Improving technology

Improving stroke treatment time is complex, and many Chicago-area medical centers are taking multipronged approaches — focusing on technology, access, and education — to get people to treatment faster.

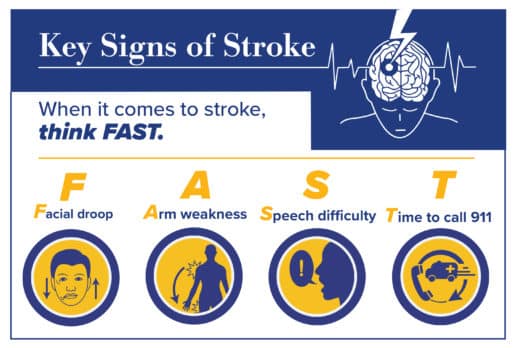

A stroke occurs when a blot clot cuts off the oxygen supply to the brain. Within minutes, brain tissue can die, so quick treatment is urgent. Strokes can also happen when blood vessels weaken and hemorrhage, causing pressure on the brain. Signs include paralysis on one side, sudden loss of speech, or facial drooping.

Shakeel Chowdhry, MD, the neurosurgeon with NorthShore University HealthSystem who saved Streiter’s life that day, says new technology made Streiter’s good outcome possible.

Chowdhry and his team were able to get Streiter to treatment in 15 minutes using a computer imaging system with artificial intelligence, called Viz.ai, which sped up a process that used to take about 45 minutes. The hospital is the first in the Chicago area to use the system.

“The sooner the [blocked blood] vessel gets opened, the better the outcome.”

The system beamed Streiter’s CT scan images to the cloud, then simultaneously distributed them to the physician and care team via a phone app. With the app, Chowdhry and his colleagues could easily look at the images together, identify the blockage in Streiter’s brain, bring in on-call staff, prepare the operating room, and get him on the table in no time.

“It lets us determine what is salvageable, how the anatomy looks, and lets us get the information quickly,” Chowdhry says. “The sooner the [blocked blood] vessel gets opened, the better the outcome.”

Previously, Chowdhry explains, it could take 20 minutes just to log in and call up the massive CT scan files, with their view of different slices of the brain. Or he would need to call a radiologist and wait for that provider to get back to him with results. Either route required valuable time.

During that precious time, a patient could lose a significant number of brain cells, which are starved of oxygen when a blood clot causes ischemic damage. Using the artificial intelligence system means patients like Streiter retain more function and have a shorter hospital stay.

“In under a minute, I can see every bit of information that I need to know,” Chowdhry says. “I’ll find out before the patient is even back in their bay in the ER.”

Increasing expertise

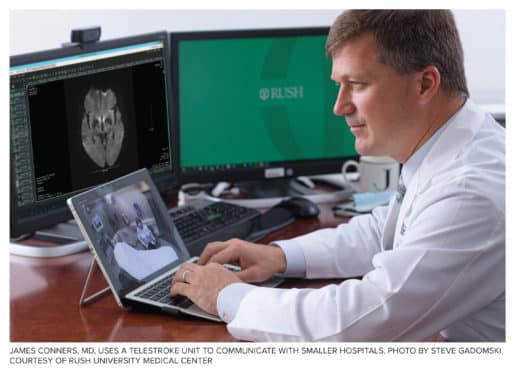

At Rush University Medical Center, health providers are using telemedicine to reach out to underserved stroke patients in the outlying Chicago area. The remote telehealth consultations help smaller hospitals improve their response times.

Using their telestroke unit, Rush physicians can assess patients in underserved areas without access to a stroke center.

“Some of these hospitals might not have access to neurologists at all,” says James Conners, MD, medical director of the Comprehensive Stroke Center at Rush. “We bring our expertise to patients who are miles away. It’s really a race against the clock.”

According to Rush statistics, approximately 33% of patients who went through the telestroke process received tPA, compared to an average of 5% of patients at other underserved hospitals. Next, providers want to use iPads to do the assessment more quickly while patients are riding in the ambulance en route to small hospitals.

Community outreach

While a quick response is essential, in many communities, stroke remains a prevalent problem.

A higher proportion of Black women in Chicago die of stroke compared to men and people who are not Black, according to the city’s 2021 report, State of Health for Blacks in Chicago.

Black adults across Chicago have a higher incidence of major stroke risk factors, including high blood pressure, smoking, obesity, and diabetes. These conditions cause inflammation and extra pressure, which can damage blood vessels and make a stroke more likely.

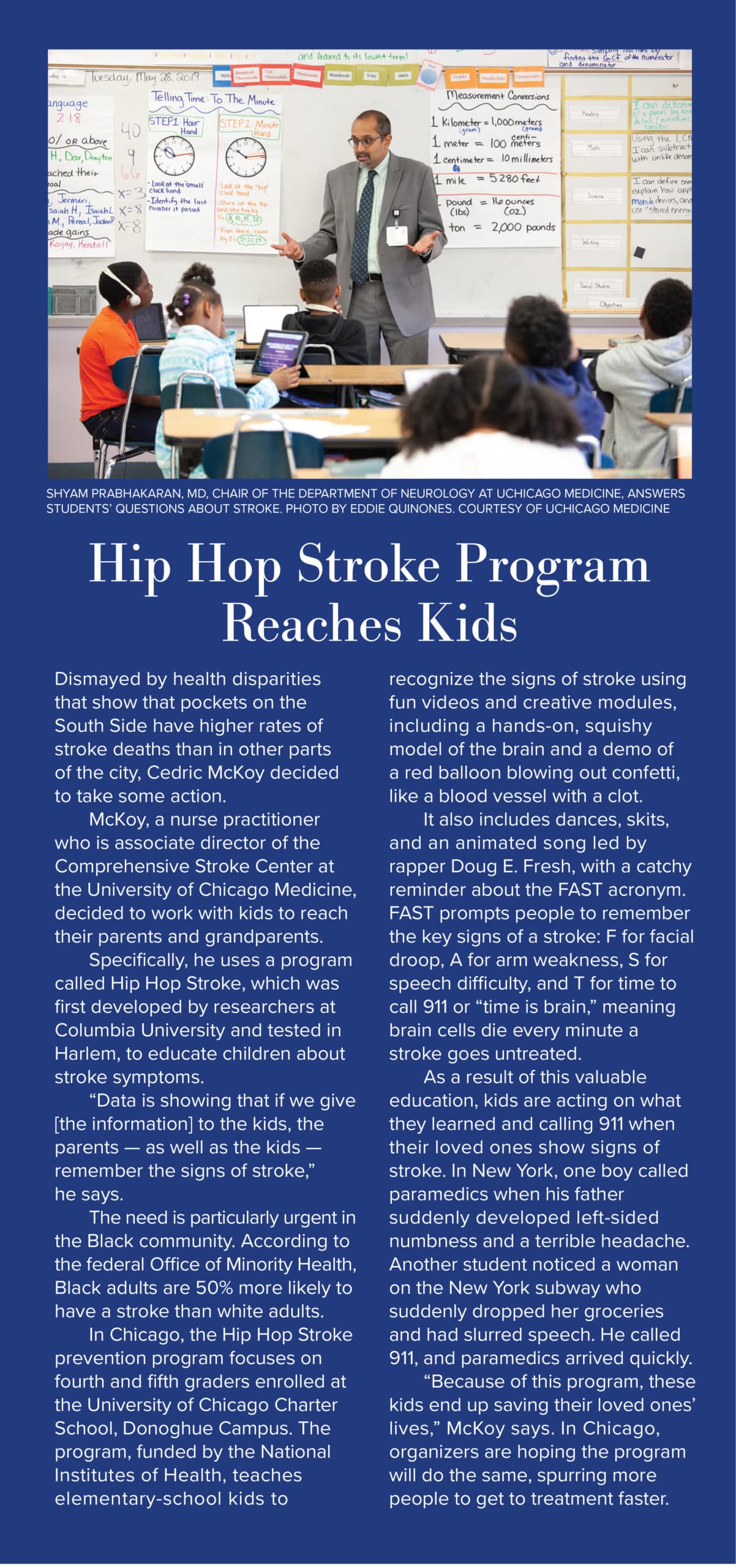

Food deserts and poor diets contribute to the underlying problems, says Cedric McKoy, an advanced care nurse practitioner and associate director of the Comprehensive Stroke Center at the University of Chicago Medicine. “In Chicago, they make it really easy to eat bad food for very little money,” he says. “A salad costs you more than a 20-piece chicken nuggets.”

For McKoy, who is Black and who cared for his father when he had a stroke several years ago, the work is personal. “It’s a calling. These are my people, and I want to change the narrative.”

McKoy researches which ZIP codes in the South Side have the highest rate of stroke and the worst response times and outcomes. He speaks to people in community centers, churches, senior centers, and festivals about how to eat healthy, quit smoking, and watch for signs of stroke.

Yet, the high rate of stroke in Black communities won’t decrease until community awareness improves, McKoy says. “We treated nearly 800 stroke patients in 2020,” he says of the UChicago Medicine stroke center. “People need to understand, on the South Side of Chicago, it’s an epidemic that is targeting our community.”

He adds, “When I go out to speak, I ask how many people have had a stroke or know somebody who did. Virtually the entire audience raises their hand.”

Too often, he says, people don’t know how to recognize a stroke when it’s happening. McKoy says the glaring disparities he sees are directly linked to the need for education about stroke prevention, both in terms of adopting a healthy diet and lifestyle as well as recognizing the signs of stroke.

The problems link back to a lack of healthcare services in underserved communities, he says. “There’s not enough people of color in medicine. [People] want someone they can relate to, someone to trust.”

Time is of the essence

Because millions of brain cells die every minute a person waits for stroke treatment, it’s important for people to know when to call 911, Chowdhry says. Many people know the signs of a heart attack, but stroke symptoms are less well known. “Stroke may not be getting the attention it needs,” he says. “Yet, the potential impact is so great.”

For stroke care, timely treatment is key. Education efforts help people recognize the signs of stroke. And new technology — whether sophisticated artificial intelligence systems or remote consulting platforms — speeds up their care.

Streiter was grateful for how quickly he was able to get treatment in the hospital, bounce back from his stroke, and return to work.

A sports fan, he admits he’s not as good at recalling sports statistics as he was, but the permanent changes were relatively minor. “I have a lot of people depending on me,” Streiter says. “It’s not lost on me how fortunate I am.”

Above image: Shakeel Chowdhry, MD, uses Viz.ai, a computer imaging system with artificial intelligence. Photos by Jon Hillenbrand. Courtesy of NorthShore University HealthSystem. Originally published in the Fall/Winter 2021 print issue.

Melissa Ramsdell is a nurse and professional freelancer specializing in health writing. She has a BSN and a master’s in journalism.