Cancer initiative spurs research—and already advancements are happening

In the 1960s, America channeled its scientific and engineering efforts into putting a man on the moon. It was a feat so large and an advancement so powerful that people were saying it couldn’t be done until the very moment that it was. With the same concentrated determination, the greatest minds in science are now working on their next ambitious target: curing cancer.

The Cancer MoonShot 2020 initiative, launched in early 2016, has a clear goal: to achieve 10 years worth of progress in cancer prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care in the next five years. To happen, it requires a change of culture, from competition to teamwork; a surge of resources, both human and financial; and a massive undertaking of data collection and analysis.

Recognizing collaboration as a key component of success, the MoonShot has brought bright minds from across the nation—and across Chicago—to work together to solve cancer’s biggest puzzles and bring an end to cancer as we know it.

Already we are seeing signs that this goal is attainable.

The role of precision medicine

At the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Stewart Goldman, MD, head of the Division of Hematology, Oncology, Neuro-oncology and Stem Cell Transplantation, is hopeful about the future. Goldman has spent his career in pediatric oncology, a field where advancements in treatments like immunotherapy and vaccines can make a lifetime of difference for kids with cancer.

“I may treat a kid for a year, but if I did my job right he or she should have another 80 years to live with what I did,” Goldman says. “We have to be careful, not just about obtaining the cure but with how we get there.”

Goldman is a member of Cancer MoonShot 2020’s Pediatrics Consortium. One of the consortium’s main goals is the development of cures that are less toxic and less taxing than intensive rounds of chemotherapy. Specialists will get there, Goldman says, with the help of precision medicine.

Precision medicine allows researchers to direct cancer treatment to the genetic makeup of individual tumors using new targeted drugs aimed at specific genetic mutations.

The precise mapping of the human genome provides a way to look deeper into the mysteries of cells. When it comes to cancer, knowing more about genes helps physicians target not just specific organs, but specific cell mutations. In pediatric and adult oncology, precision medicine has made it possible to expand beyond cytotoxic chemotherapy—chemo drugs that are poisonous to cancerous cells as well as some healthy ones.

“With precision medicine, we can select therapies that have a better chance of being effective,” says Massimo Cristofanilli, MD, associate director for translational research and precision medicine at the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University and director of its precision-medicine-based program for advanced cancers, Lurie Cancer Center’s OncoSET Clinic.

“So much of precision medicine has focused on studying the detailed characteristics of a tumor,” Cristofanilli says. “But we also need to focus on the impact this molecular information has on the patient. For OncoSET that means mapping the tumor DNA in an individual’s genes to identify abnormalities and determine how

they influence the tumor’s behavior. This information is then used to select the best individualized treatments and to measure the patient’s response to therapy.”

The promise of immunotherapy

Part of creating less taxing cures is harnessing the innate healing properties that exist within our own bodies. Immune systems act as defenses against disease, attacking abnormal cells and substances that enter the body. Some cancer cells, however, have found a way to elude this powerful response. It’s at this moment, Cristofanilli says, that we need another strategy.

The newest cancer approaches employ immunotherapy treatments that train immune cells to attack specific cancer cells.

“It’s really to capitalize on using the patient’s own immune system to take on individual tumors,” Goldman explains.

In a healthy person, the body’s natural defenses are organized such that immune cells recognize and attack abnormal cells before they can spread. Some cancers have found a way to manipulate this system, tricking the body into thinking they are normal cells and avoiding an immune attack.

One type of promising immunotherapy, called checkpoint inhibitors, directly addresses this problem, subverting cancer cells’ ability to misrepresent themselves. As researchers become better at recognizing the unique ways that cancer cells go undetected by the immune system, they are developing more drugs to unravel the process.

Side effects of immunotherapy drugs tend to be less than classic chemotherapy, for example a rash as opposed to nausea and hair loss. Immunotherapy is a burgeoning field of cancer treatment and holds significant promise in the continued search for less-toxic cures.

“It’s clear that killing cancer cells [via chemotherapy] in combination with reactivating or removing the brakes on the immune system is more effective, particularly because tumors become resistant and change over time,” Cristofanilli says.

Oncology continues to move toward utilizing combinations of therapeutic techniques, applying what is understood about a patient’s individual tumor to target mutations and enable the immune system to attack.

Unleashing the power of data

As cancer care gets more effective, it also gets more complicated. Experts are quickly learning about the multitudes of ways genes mutate and disseminate, and of the various ways they can and cannot be treated, creating a mass of data in the process. Properly leveraging this data will become only more important as the wealth of information grows.

Physicians have a moral and ethical obligation to make sure that the information they learn is used to its fullest potential and that it’s shared carefully, correctly and thoughtfully, Goldman says.

Therein lies another major goal of Cancer MoonShot 2020—to facilitate the large-scale sharing and analysis of data so that all can benefit from the advances being made at individual institutions.

Think of your DNA like a library and gene sequencing like spellchecking every single book in that library, says Peter Hulick, MD, head of the Division of Medical Genetics at NorthShore University HealthSystem. “As we look to the future we are scanning the entire content of the library, the entire genome. We’ll get there from a technology standpoint, but the significant challenge will be managing that data, putting it in a useful framework so that physicians who may not be genetics experts are able to use that information effectively.”

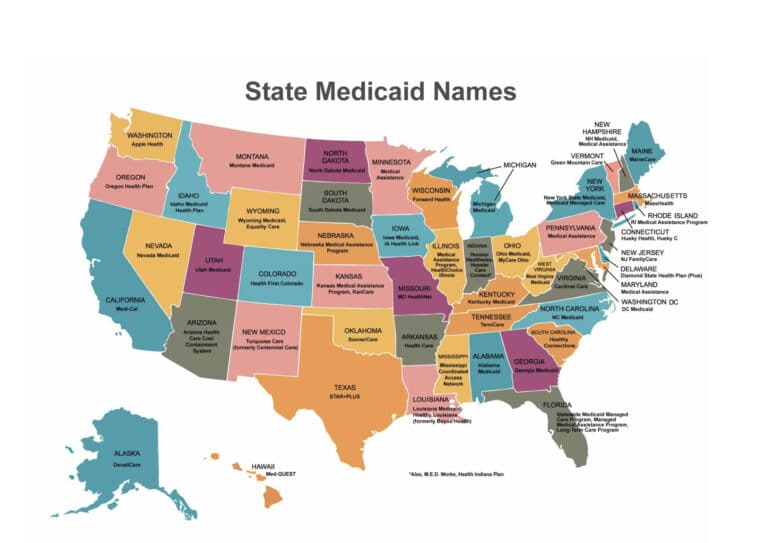

The MoonShot has spurred dozens of task forces with the goal of unleashing the power of this data. No single institution can see enough patients to understand all the human variability related to genetic changes, Hulick says, so it’s critical to have these sources to pull data for analysis. Initiatives like the National Cancer Institute’s Genomic Data Commons (GDC) and Integrated Data Engagement Analytics (IDEA) are uniting national efforts to bring better care to more patients.

One area that will surely benefit from better data access is clinical trials. Clinical trials are often the first steps in bringing new treatments to the mainstream. These studies are crucial for new developments and can also present hope for patients who have exhausted other options—yet, few patients participate.

The National Cancer Institute estimates that only 3 percent of cancer patients participate in clinical trials. Some 40 percent of trials fail to achieve minimum patient enrollment, including more than 60 percent of phase 3 trials. And trials that do reach their participation requirements often fail to share their findings within a reasonable period of time. The result is a lot of wasted time and effort and a largely underutilized resource for developing new treatments.

Organizations like the National Brain Tumor Society and the Cancer Support Community have launched landmark efforts to offer new approaches and resources to cancer patients who wish to participate in trials, removing many of the barriers that make participation so difficult for patients.

Stopping cancer before it spreads

As the MoonShot facilitates rapid advances in treatment and care, Vadim Backman, PhD, is working on a complementary approach with revolutionary potential: prevention.

At the Backman Laboratory at Northwestern University, Backman and his team are using a method called nanocytology to screen for cancers at early, treatable stages.

Nanocytology, which is currently in clinical trials, looks at changes in a cell’s chromatin—the substance that forms chromosomes during cell division, what Backman refers to as the cell’s “software.”

“[Chromatin] is what allows cells to mutate, to evolve, eventually becoming more aggressive and more dangerous,” Backman says. Nanocytology analyzes a cell’s chromatin, locating precancerous and cancerous lesions at their earliest stages.

“Cancer is not a disease of one gene; it’s a disease of mutation of hundreds of genes,” Backman says. “This test can tell you whether you have cancer; it can tell you whether the cancer is aggressive; it can tell you whether in the future you might develop cancer; it can tell you whether the cancer is likely to survive chemotherapy. It all boils down to how abnormal the software is.”

If all goes according to Backman’s plan, as early as 2018 patients will be able to go to their primary care physician to get a simple swab of their cells, which will then be sent off to a lab and analyzed for these abnormalities. Backman estimates that this screening measure could reduce mortality rates for specific cancers by as much as 90 percent.

The future, as imagined by the physicians and experts on the frontline of the cancer fight, is bright. Imagine a world where cancer is as manageable as diabetes, where a child can take a pill and go to school instead of spending weeks in the hospital, where an aggressive cancer is never even given the chance to spread. This is the future that cancer specialists are hoping for.

The rate of advancement in cancer care, combined with unprecedented collaboration, suggests that the progress we’ll see is even greater than initially intended—especially at the local level.

“Change is coming,” Goldman says. “It’s happening one step at a time, but it’s happening with quick steps.”