Researchers in Chicago are studying how PFAS affect health and where people might be exposed

Ken Lumb, managing partner at Chicago-based law firm Corboy and Demetrio, started getting calls from firefighters last year: men and women with kidney, prostate, and bladder cancers. They were interested in filing lawsuits based on their health issues. The very gear that protected them on the job, they suspect, contains toxic chemicals called perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, that have the opposite effect on their health.

Firefighters are no strangers to cancer. They’ve always had a significantly higher rate of death by cancer compared to the general population. “But as safety gear and procedures have gotten better and better, and self-contained breathing apparatuses have become better, those rates have not gone down,” Lumb says. “There’s something else at play, and we believe these PFAS chemicals are a substantial factor.”

The firm now represents more than 100 firefighters and gets two or three calls a week from prospective clients.

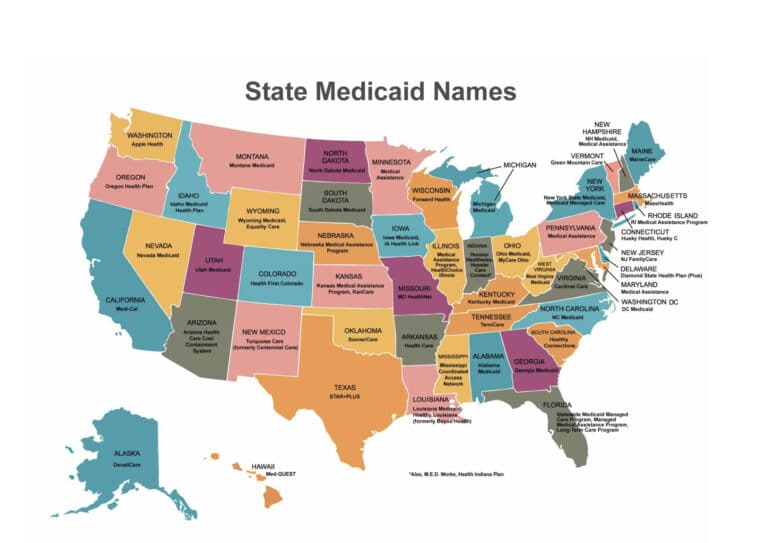

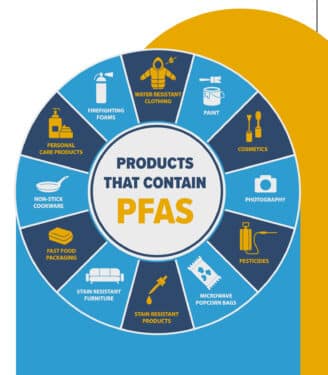

But PFAS aren’t only in firefighting gear. The chemicals are in hundreds of products people use every day, including food packaging, clothing, cleaning supplies, and more. PFAS make pans nonstick and cushions fire-resistant. That’s what sold companies on them, when 3M first began manufacturing the chemicals in the 1950s.

Today, PFAS leak from landfills, manufacturing sites, and military bases, where troops conduct exercises using firefighting foam that contains the chemicals. Once in the environment, PFAS rarely degrade, and they move easily in water, contaminating drinking water sources. That includes Lake Michigan, which 10 million people rely on for water.

Measuring exposure

In fact, up to 45% of U.S. tap water contains at least one of the 32 types of PFAS tested (of more than 12,000 PFAS overall), according to a U.S. Geological Survey study published in June. The researchers also said that exposure to the chemicals from drinking water was likely higher in cities and in certain parts of the country, including the Great Lakes region.

That persistence has earned PFAS the moniker of forever chemicals. And not only are PFAS forever, but they’re everywhere. They show up in 99% of Americans’ blood, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. When 3M scientists studied PFAS in humans, the only PFAS-free blood they could find, as a control group, was archived blood samples from Korean War military recruits.

Scientists now are digging into how PFAS influence the hormonal system and potentially increase cancer risk.

“There’s a lot of research that has been done and is continuing to be done, on people across a broad spectrum of diseases,” says Gail Prins, PhD, co-director of the Chicago Center for Health and Environment at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Prins is looking at the effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals, including PFAS, on cancer.

Though early studies on PFAS and health focus on people who live or work near areas with high PFAS concentrations, increasingly scientists are turning to the effects of exposure at lower levels.

“The general population is exposed to a much lower level of PFAS compared to those who live near or work in PFAS manufacturing or production facilities,” says Jiajun Luo, PhD, an epidemiology fellow studying PFAS at the University of Chicago. Yet, he adds, “If PFAS is indeed a carcinogen, there may not be a threshold.”

Even low levels could contribute to negative health outcomes.

“I think it’s shifted a lot relatively recently,” says Harvard University toxicologist and environmental scientist Elsie Sunderland, PhD, who investigates PFAS exposure. The research originally focused on industrial sites. “Now you’re seeing discussion of a broader assortment of cancers linked to PFAS exposure and also for more general populations,” Sunderland says.

To understand why, consider what we know about particulate matter, such as soot and dust in the air, researchers say. Three decades ago, scientists thought that inhaling low levels of particulate matter smaller than 10 micrometers would not result in negative health effects. Today, we know that exposure to particulate matter as small as 2.5 micrometers can have a substantial effect on human health.

Reducing PFAS

Scientists are finding that PFAS can wreak havoc on the body’s hormones. The chemicals interfere with organs such as the thyroid and affect estrogen and testosterone levels. This disruption can potentially lead to reproductive problems and issues for pregnant people, such as gestational diabetes and high blood pressure.

In the past decade, research also has linked PFAS exposure to testicular and kidney cancers. At the Chicago Center for Health and Environment at the University of Illinois at Chicago, Prins is looking into how PFAS exposure at various levels could affect metabolism and contribute to cancer risk.

Metabolism is fundamental to speeding cancer’s growth and aggression, Prins says. “I’m very concerned that the PFAS chemicals, which bind to the same receptors that control metabolism, might be providing more fuel to that fire.”

In March 2023, the federal government proposed the first drinking water standards for some PFAS chemicals, part of an effort to reduce PFAS pollution and protect public health. If finalized, the standard would require public water systems to monitor for these chemicals and inform the public when levels exceed the set limit. In Illinois, the state EPA has already begun to sample water for PFAS and map their findings — information that could be used to limit exposure.

One way to limit exposure: by eliminating PFAS in drinking water altogether. Northwestern University chemist William Dichtel demonstrated one option in a paper published earlier this year. “They’re called forever chemicals because they don’t break down in the environment. It doesn’t mean they don’t break down under other conditions. It just means they’re hard to degrade,” Dichtel says. “Those possibilities are out there.”

Originally published in the Fall/Winter 2023 print issue.

Susan Cosier is a Chicago-based writer focused on science and the environment. Her work has appeared in Scientific American and Science.