Options preserve hope for pregnancy after treatment

When 31-year-old Amy Glomski was planning her perfect wedding, a pandemic wasn’t part of it. Nor was cancer treatment, and, most certainly, infertility was not part of her plan.

Yet, while the Chicago resident was in the midst of planning her June 2021 wedding, she found a lump in her breast. After an ultrasound, mammogram, and biopsy, her doctor diagnosed her with HER2-positive breast cancer, a form of cancer that tends to grow and spread faster than other breast cancers.

Due to the cancer’s aggressiveness, Glomski’s oncologist recommended surgery, chemotherapy, and two targeted immunotherapy drugs. Depending on the result of her treatment, she may also need radiation.

Before Glomski began chemotherapy, her oncologist informed her that treatment could affect her ability to have children. Chemotherapeutic agents can damage ovarian eggs, significantly reducing fertility.

“My mind was overflowing with every possible fear about getting married and wanting a family,” Glomski says. “Having children was part of [our] plans for our future. Once I was aware that cancer could cause me to lose my fertility, I told my doctor

I wanted to do what I could to have kids.”

Glomski is one of about 67,000 women under age 45 diagnosed with cancer every year, according to the National Cancer Institute. These women face tough choices about cancer care and its impact on future pregnancies.

Freezing eggs brings hope

Glomski’s oncologist referred her to fertility specialist Jennifer Hirshfeld-Cytron, MD, director of the fertility preservation program at Fertility Centers of Illinois, who told Glomski about the risks of exposing eggs to destructive chemo agents.

“Because women are born with a fixed number of eggs, once the impact has occurred, there is nothing to do to bring back those eggs. We have to be proactive to freeze eggs or embryos before the chemotherapy is given,” Hirshfeld-Cytron says.

The American Cancer Society states that the risk of infertility varies depending on the individual’s age, type of surgery, and type and dose of treatment. Hirshfeld-Cytron says the treatment Glomski is receiving puts her at a high risk of no longer getting her period after her treatment ends, which consequently puts her at a greater risk of becoming infertile.

Fortunately, cancer treatment has progressed, and specialists are able to offer options to women wishing to preserve their chances of having a baby.

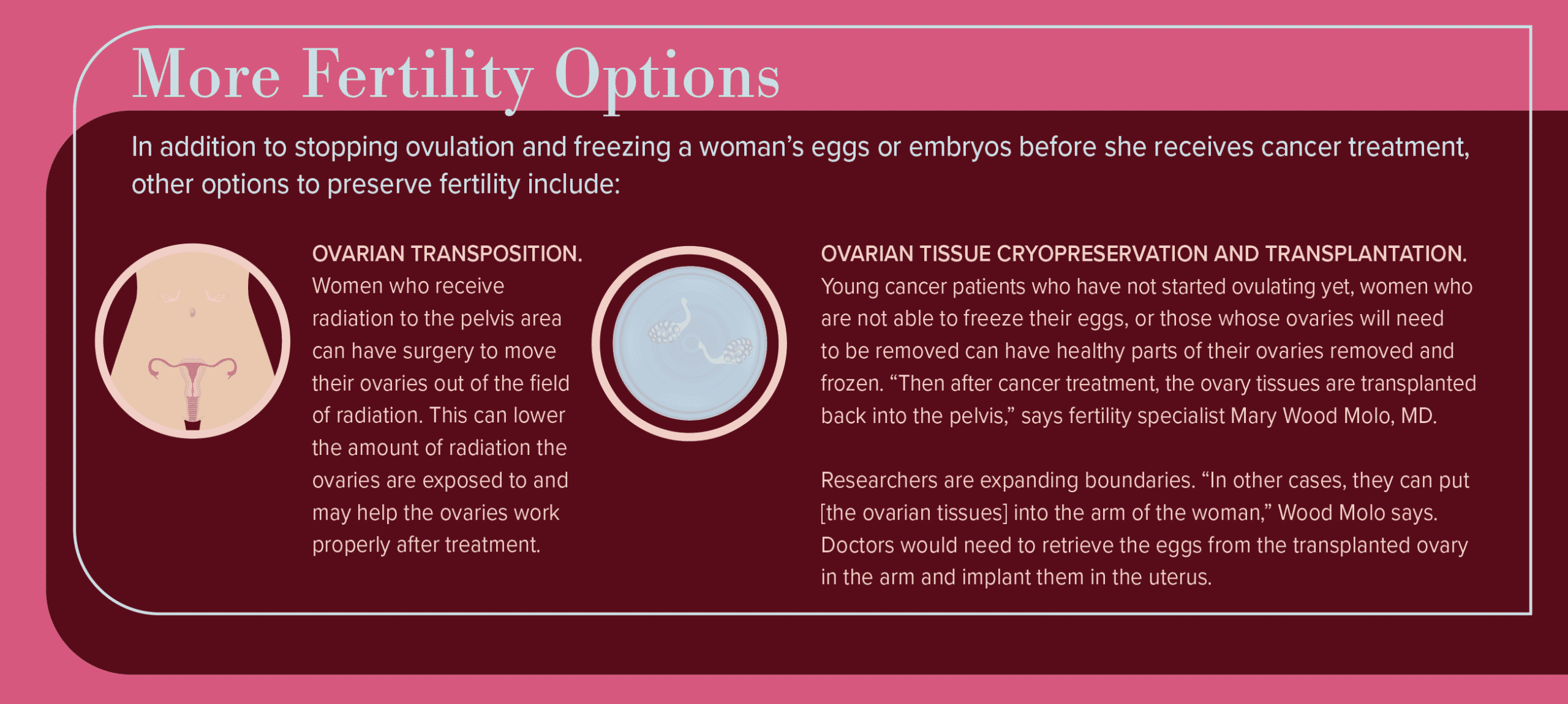

“In this day and age, versus 10 or 20 years ago, the science behind cancer treatment is so much better, so the goal of the oncologist is to deal with the cancer and keep [women’s] reproduction options open for the future,” says Mary Wood Molo, MD, founder of the Center for Reproductive Care and medical director of the IVF center at Rush University Medical Center.

When preserving fertility, timing matters. For instance, women with breast cancer usually have less than a month between diagnosis and treatment. “During that time, there is time to freeze her eggs, if we are informed right away,” Hirshfeld-Cytron says.

The process of freezing eggs involves taking injections of a medication for two weeks to stimulate the ovaries. In a 15-minute procedure, the doctor retrieves eggs via a transvaginal ultrasound-guided procedure while the person is under twilight anesthesia.

“The majority of women are back at full function and work the next day. Most women can receive chemotherapy the next day,” Hirshfeld-Cytron says.

Risks for this procedure include the same risks of in vitro fertilization, Wood Molo says. “Elevated hormone levels can increase risk of blood clot formation, and those who have cancer do have risks of blood clot formation. You want to identify those risks and reduce them as much as possible,” she says.

However, the procedure is safe. “Studies have shown in women with breast cancer, the use of medications to get eggs out does not advance their cancer or reduce their risk of survival,” Wood Molo says. “They don’t have to pick one thing in lieu of the other.”

Options for pregnancy

In some instances, if the first retrieval is unsuccessful, there is time for a woman to have another egg retrieval before starting treatment.

Glomski only needed one round of egg retrieval, as 18 of her eggs were viable to be frozen. She started chemotherapy two days later. Some people choose to take another step and create embryos for freezing, instead of freezing unfertilized eggs.

Glomski chose to take the medication Lupron, which temporarily stops the ovaries from producing estrogen and suppresses her periods during treatment. Lupron can help protect the ovaries and increase the likelihood that periods and ovulation will return once cancer treatment ends.

“The hope is that I may be able to begin ovulating again and potentially have a natural pregnancy. If not, I have my frozen eggs to turn to,” Glomski says.

Whether women who receive cancer treatment can use their frozen eggs to achieve pregnancy depends on several factors, such as how well they respond to treatment, if their ovaries or uterus are impacted, and if they need to take ongoing hormone therapy medications such as tamoxifen, which may harm a developing baby.

After finishing cancer treatment, women may need to wait at least two years before trying to get pregnant, according to the American Cancer Society, in order to reduce the risk of birth defects from chemotherapy and to make sure the cancer doesn’t recur.

Once a woman is ready to try to achieve pregnancy, her eggs will be thawed and fertilized to create embryos. Then she will take a series of medications before specialists place the embryo into her uterus.

Another option is to use a gestational carrier — a woman who carries the pregnancy on behalf of another person.

The past year has been challenging for many reasons, but Glomski looks forward to when she is cancer-free and ready to think about a baby. “I’m incredibly grateful that we have options for when I’m on the other side of cancer,” she says. “Knowing we have an avenue for a family gives me hope.”

Originally published in the Spring/Summer 2021 print issue.

Cathy Cassata specializes in health, mental health, and human behavior. She connects with readers in an insightful and engaging way.