By Heidi Lading Kiec

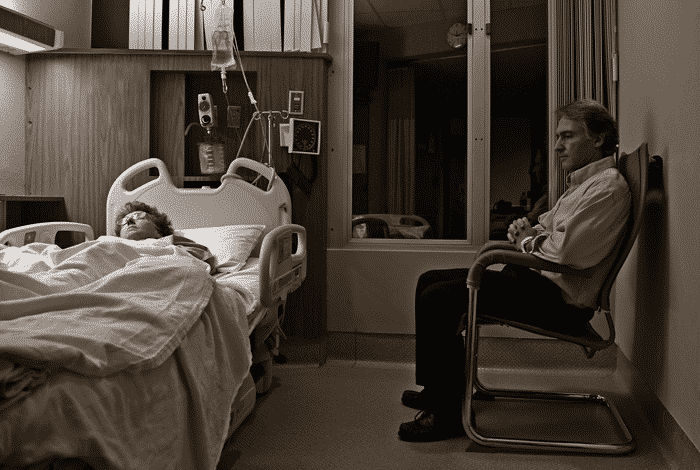

Winston Churchill once said, “Courage is what it takes to stand up and speak; courage is also what it takes to sit down and listen.”

This quote, found in many leadership books, is applicable to a host of situations, but it’s especially relevant to individuals and their loved ones facing end-of-life decisions.

The American Psychological Association defines end-of-life as the time period when healthcare providers expect a patient’s death to occur within six months.

A survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that although most Americans would prefer to die at home, only one-third actually do. This number is on the rise, as is the number of patients choosing to die in hospice care, but more can be done to ensure that individuals die according to their wishes. Discussions about those wishes need to happen with doctors and loved ones; however, that’s not always easy.

“It’s almost countercultural to have a conversation and think about preparing for death,” says Dan Ross, certified Jungian psychotherapist and director of clinical services at Heartland Hospice. “We have a deeply embedded cultural attitude that is biased toward the myth of the hero, where death is something to be avoided and battled.”

“Care conversations need to start early but can evolve over time,” says Gordon Wood, MD, associate medical director of Midwest Palliative & Hospice CareCenter, assistant professor of medicine at the Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine and director of Palliative Medicine and Supportive Care at Northwestern Lake Forest Hospital.

“When people don’t have these conversations in great detail early in the course of their illness, it robs them of the opportunity to work with their medical team to develop a care plan that matches their values and helps them meet their goals. Many patients who don’t have these conversations end up receiving painful, invasive interventions that their families say they wouldn’t have wanted if they had [had] the chance to talk about it ahead of time,” Wood says.

Wood encourages patients diagnosed with a serious illness to find a time when they are still feeling well enough to discuss with their physician and family members their wishes for their future medical care and how they want to live through the remaining time in their life, especially regarding their goals, values, hopes and fears.

It can also be helpful to discuss medical scenarios that may represent an unacceptable quality of life. For example, many ALS patients will eventually have to choose whether they want a feeding tube, and this may represent a quality of life that is acceptable to some patients yet not to others. According to Wood, the only way the medical team knows how to proceed is if patients have expressed their wishes. Dementia, congestive heart failure, cancer and all other serious illnesses come with similar decisions, and these decisions often have to be made when the patients are too sick to communicate their wishes. Wood recommends that patients talk with their doctors early so that when the time comes, the doctors can do everything that individual patient would want and nothing that wasn’t wanted.

A patient’s wishes can be put into writing through advanced directives such as a living will. And a decision-maker who knows these wishes can be named through a Power of Attorney for Healthcare form. But these forms are only helpful if they are readily available and based on careful conversations involving the patient, the individual acting as power of attorney for healthcare and the medical team.

“Advanced directives are not always visible or honored,” Ross says.

Illinois legislation that was passed in August 2014 seeks to change that. A practitioner order for life-sustaining treatment (POLST) is a medical order signed by a physician or other medical practitioner and must be followed. The order indicates the patient’s preferences for end-of-life care and allows specific decisions to be made about resuscitation, ventilators, artificial nutrition, hydration, transfers to hospitals and intensive-care units, and comfort-focused care. The order is portable and follows an individual everywhere.

Since POLST is a signed medical order, a conversation with a medical practitioner is a required part of the process. This communication is extraordinarily beneficial. Studies have found that a person’s level of stress decreases and that that person’s ability to cope with illness increases when options for care are discussed with one’s doctor early on.

Palliative care, designed to treat a patient’s mental, physical and spiritual well-being, should also be discussed with a medical practitioner and loved ones early on. Hospice care, a leading form of palliative care, is often misunderstood by families and individuals who believe that an illness should be fought until the very end, Ross says.

“The mistaken belief is that choosing hospice care means you’re giving up, and that can create conflict within families,” he says.

However, studies have found that patients receiving palliative care have symptoms that are better controlled, lead a better quality of life and may even live longer than patients with similar illnesses not receiving palliative care. Loved ones experience less anxiety, and those appointed as caregivers suffer less posttraumatic stress disorder when palliative care is at hand.

Hospice care is administered wherever the patient lives and may include social workers, spiritual care advisers, hospice aides, volunteers, nutritionists, pharmacists and therapists—including those focused on music and art.

Early and open communication can help patients and their families come to terms with what patients want for their care and how they choose to die.

Patients’ end-of-life wishes are more likely to be met when the goals have previously been discussed. Those who want a peaceful death at home need to have the courage to speak up. And their loved ones need to have the courage to listen.

Originally published in the Fall 2015 print edition

Resource List

Aid for individuals and families facing end-of-life decisions

Cancer Wellness Center

cancerwellness.org

The Center to Advance Palliative Care

getpalliativecare.org

The Conversation Project

theconversationproject.org

Final Roadmap

finalroadmap.com

Illinois Hospice & Palliative Care Organization

il-hpco.org

Midwest Palliative & Hospice CareCenter

carecenter.org

POLST Illinois

polstil.org

Handbook for Mortals: Guidance for People Facing Serious Illness

By Joanne Lynn, Joan Harrold, Janice Lynch Schuster