Support helps families come to terms with looming loss

Last April, Rogers Park resident Aisha Luster got the biggest shock of her life when she learned that her father was diagnosed with stage 4 esophageal cancer. “He didn’t tell me or my older sister,” says Luster, 37. “We were crushed. We felt left in the dark. It was devastating.”

Within two months of sharing the gut-wrenching news, Luster’s father died. “He spent the last week of his life in a hospital alone due to Covid,” Luster recalls. “That was one of the worst days of my life. I never knew I would lose him. I have definitely been affected mentally, physically, and emotionally. It still feels like a bad dream I can’t get out of.”

Luster’s father was one of an estimated 606,520 Americans who died of cancer in 2020. Grief, depression, panic, and anxiety — for both the individual and their family — are common when dealing with terminal cancer.

Facing imminent loss is not easy. Yet, end-of-life support from palliative care services, such as hospice care, can help patients and their loved ones cope with these emotions and prepare them for what to expect.

End-of-life discussions

Talking to family members about their wishes can help make choices easier for caregivers.

“Families are under an enormous amount of stress, especially if the medical problem came suddenly and they didn’t have any opportunity to talk to the patient or to anticipate the problems,” says sociologist Susan P. Shapiro, a research professor at the American Bar Foundation in Chicago and author of Speaking for the Dying: Life-and-Death Decisions in Intensive Care.

To watch their body breaking down before your very eyes definitely had a huge impact on me.”

End-of-life discussions establish transparency and prevent misinterpretations of the individual’s final wishes, she says. “When patients never spoke to family members in advance about what they wanted, family members were very, very torn about what they should do.”

For those living with terminal cancer, coming face-to-face with their looming mortality can be painful.

Between 15% and 50% of cancer patients experience depressive symptoms, according to a review article in the journal Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. Depression in cancer patients contributes to physical and psychological problems, it says. And depression may be associated with higher death rates.

Christine Schwartz-Peterson, MD, is a hospice medical director at JourneyCare, a hospice and palliative care agency that’s headquartered in Glenview and serves 13 counties in Illinois. Part of her role involves caring for terminally ill patients who experience depression or anxiety.

“Our patients and their loved ones are going through tremendous loss while on service with us,” Schwartz-Peterson says. “Our skilled hospice teams, which include social workers and chaplains, are trained to recognize this pain and help support them throughout this difficult time.”

Social workers provide resources such as emotional support, counseling for patients and caregivers, and funeral planning that reflects the patient’s final wishes. Chaplains, tasked with easing spiritual healing through physical and emotional pain, aid patients and families with some comfort in spite of illness.

Relying on such services helped Lombard resident Melissa Schmitz.

In 2016, when she was 44, her father was diagnosed with stage 4 pancreatic cancer.

“There’s really no way to prepare for that. To watch the person you love, who has always taken care of you your whole life, to watch their body breaking down before your very eyes definitely had a huge impact on me,” Schmitz says. “But there was nothing I could do to actually fix it or help it, and that was devastating for me.”

Ultimately, palliative care, which supports patients and their families, enabled her to reach peace with the end-of-life process. As her father’s cancer progressed in the last weeks of his life, the Schmitz family decided to move him to hospice care.

With the help of hospice physicians and social workers, Schmitz was able to provide her father with individualized end-of-life care. “I was pleasantly surprised. I didn’t want him to be in a hospital room, and he didn’t want to be in a hospital room,” she says. They all achieved a measure of peace. “JourneyCare allowed me to basically move in for the last couple of weeks. I never had to miss a minute with him. And that was wonderful.”

Supporting the overlooked

It’s important to support the mental health of family caregivers as well as patients, says Dana Delach, MD, a JourneyCare physician specializing in hospice and palliative medicine. Caregivers, who are often physically and mentally exhausted, can be overlooked when someone is dying.

Friends and family can step in to listen, care, and offer support. “If you know someone who is a caregiver, it is important to ask how you can help,” Delach says. “Sometimes the best gift you can give a caregiver is the gift of being present. Truly present. Sit with them while they provide care. Be a person to listen as they express their myriad emotions.”

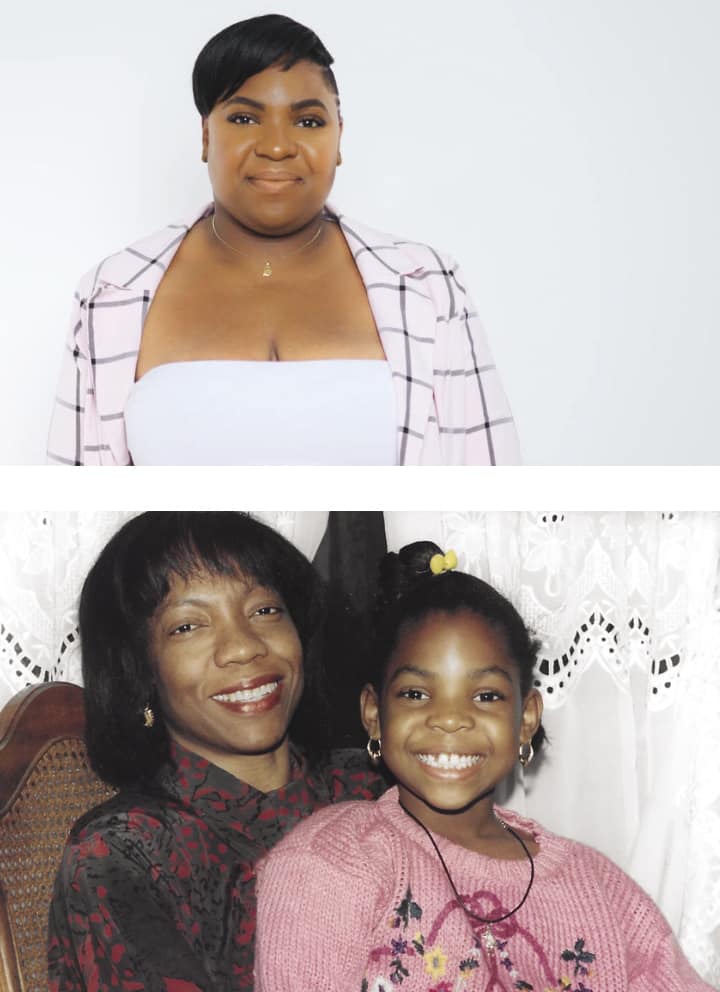

Like Luster and Schmitz, Lincoln Park resident Simone Malcolm understands the signifi-cance of addressing family mental health during this difficult time.

In 2010, Malcolm’s mother revealed to her that she had breast cancer. At the time Malcolm was 20 years old. “When my mother first told me of her diagnosis, I was devastated because I thought I was going to lose my mom. I was scared, and because of that, I wasn’t there for her as I should have been,” Malcolm says. “I put a lot of my focus on school, my friendships, and hanging out. I acted as if everything was normal and I didn’t have a sick parent.”

Complicating matters for Malcolm’s mother was that she was initially misdiagnosed. By the time she was properly diagnosed, the cancer had reached stage 3. “My mother was hopeful that she would beat the disease,” Malcolm recalls. “Because of this, we did not speak about what would happen if she was to become incapacitated.” Her mother passed away later that year.

Drawing from her experience, Malcolm offers recommendations for those facing the same situation she did a decade ago. It’s important to be present for loved ones and involved in their care, she says.

“The advice I would give is to make sure the family stays on top of doctor’s visits and make sure they ask a bunch of questions so they are informed,” she says. “Also, be there for your loved one. They need all the support and love.”

Originally published in the Spring/Summer 2021 print issue.

Alex Camp is a freelance journalist with a master’s in public administration, specializing in public affairs reporting, from University of Illinois Springfield.