As Covid-19 stress continues, domestic violence escalates in Chicago

Life had been dangerous enough for Elise, whose name has been changed for safety.

The mother of twins was living with her husband, who was also her abuser.

Then the Covid-19 pandemic hit, and Elise’s husband lost his job in the service industry.

The family had to rely on the little savings they had gathered to cover rent and basic necessities. With the additional financial stress, Elise’s husband hit her even more.

Elise longed to escape. But she knew that a survivor’s risk of being killed is highest when they leave or threaten to leave.

Complicating matters, for the past year health officials have encouraged everyone to stay home to save lives. But what do you do when your home is no longer a safe place?

When you’re isolated from friends and family, confined with an abusive partner who uses that isolation to further control you?

When your partner has abused you — physically, verbally, emotionally — in front of your children?

When being shut in with the person abusing you makes it harder to seek help?

As the days and months of the pandemic wear on, the stresses — and dangers — mount for those experiencing domestic violence.

Despite all the obstacles that Covid-19 is throwing their way, domestic violence advocates in the Chicago area continue to reach out to survivors. They’re also seeking to change the way that police and courts respond, pushing for an expansion of community-based services and the development of a nonpolice response.

Increased isolation

“While for many people it is safer to be at home, for people who are experiencing domestic violence, that may not be the case,” says Kesha Larkins, associate director for Connections for Abused Women and their Children (CAWC). The Chicago organization operates Greenhouse Shelter, Humboldt Park Outreach Program, and two hospital-based programs and also provides domestic violence education at Haymarket Center, a substance abuse treatment facility in Chicago.

People who abuse often use violence, degradation, and isolation against their victims. And the pandemic’s isolation is making matters worse, says Damaris Lorta, chief development officer of A Safe Place, a domestic violence agency in Lake County.

“For a lot of our clients, going to work or dropping off their kids at school is their outlet for connection to the world and to their support systems. Going to church, going to work, you have your support there,” she says. “The stay-in-place order cut that off completely.”

When life feels out of control — like it has during the pandemic — stressful issues spiral. Add in domestic violence, and life becomes dangerous.

“People’s home and personal relationships are complicated in the best of circumstances. So when you throw in issues of power, control, coercion, and emotional, physical, and financial violence, it gets a lot more complicated,” says Vickie Smith, executive director of the nonprofit Illinois Coalition Against Domestic Violence, which provides education and support to domestic violence programs across the state.

“Domestic violence is — I can’t emphasize it enough — mostly not physical violence. It’s a lot of coercion, manipulation, and financial manipulation,” Smith says.

People who abuse have also been using Covid-19 as a weapon. Some have withheld items like hand sanitizer or disinfectants or have used misinformation about Covid-19 to pressure or frighten their partners.

“We’ve had clients, especially toward the beginning of this, if they had [Covid-19] symptoms or their partner had symptoms, [their abusive partner] wouldn’t allow them to go for medical care,” Lorta says. “They were afraid of their abusers infecting them or not allowing them to get the support that they needed.”

Maya, a client at A Safe Place whose name has been changed for safety, experienced such abuse. “We have been home for weeks. We are not working,” she says. “For some reason, last night he got it in his head that I was trying to give him Covid and beat me so badly I ended up here [in the hospital].”

About one in four women and one in 10 men experience sexual violence, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetime, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Reports of domestic violence have risen during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The Network, a nonprofit organization that serves Chicago-area domestic and sexual violence agencies, operates the statewide Illinois Domestic Violence Hotline. In 2020, the hotline received 28,749 calls statewide, a 16% increase from the previous year. And from March through December 2020, it responded to 936 text messages, a 2,430% increase from 2019.

“Texts are quiet,” explains Amanda Pyron, executive director of The Network. “You can text from your closet, and your partner doesn’t necessarily know that you’re reaching out for help.”

Pyron noticed another difference in the hotline contacts during the pandemic. Typically, hotline callers are primarily interested in emergency shelter. But during the pandemic, more people have been reaching out for safety planning. Unable to leave for various reasons, they’ve been asking how to stay safe in their own homes, how to manage a relationship with a partner who is abusive.

Finding shelter

Elise knew she couldn’t leave with her twins. She wouldn’t be safe. Not yet. So she contacted a domestic violence service provider near her home and learned about ways to protect herself and her children while living with an abusive partner.

Through its emergency response fund, The Network provided Elise with rental assistance so she and her children can remain in their home, until it’s safer to leave.

Financial stress, worsened because of pandemic job losses, can make it harder to escape the abuse, Larkins says. “About 80% of our clients are under the poverty guideline level,” she says. “Losing their financial ability has been something that’s been a common theme.”

Throughout the pandemic, domestic violence programs have been supporting survivors by providing them free emergency housing, clothes, food, counseling, transportation, and assistance finding permanent housing.

But domestic violence shelters, most with communal kitchens, common living areas, and shared bathrooms, are not set up for social distancing. Many had to reduce bed capacity to maintain distancing requirements.

There are about 150 beds in domestic violence shelters in the city of Chicago. Of those, 42 are at CAWC’s Greenhouse Shelter. But to space out during the pandemic, the shelter needed to decrease capacity to as low as 20 beds.

“We were able to supplement with a hotel program that we ran while we had temporary funding to do that,” Larkins says, “but it’s expensive, so that’s not something we are able to maintain permanently.”

From the end of April through June, the Illinois Department of Human Services provided $1.2 million for additional emergency shelter through hotel rooms, Airbnbs, and corporate housing.

In Lake County, A Safe Place went from being able to house 33 individuals in its emergency shelter building to housing 105 individuals in hotel rooms. At the end of July, single clients moved back into the shelter, while some families remained in hotel rooms and alternative spaces. In December, the program provided emergency shelter to between 50 and 70 individuals.

Children in danger

The increased abuse during Covid-19 has affected children, too. Some have witnessed a parent being abused; others have been physically or sexually abused themselves.

And while the number of domestic abuse reports rose, the numbers for child abuse decreased. In April 2020, reports of suspected child abuse and neglect were down more than 50% from April 2019, according to the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS). Reports have inched up but are still below typical levels. In September, reports were down about 18% from the previous September.

But while reports of child abuse dropped, experts suspect that the amount of abuse has actually increased. The reason for the discrepancy: Many children are no longer going to school in person, where mandated reporters might notice something amiss.

Mandated reporters — such as teachers, social workers, and clergy members — are trained to recognize signs of child abuse and are legally required to report any suspicions of abuse. “All those safety nets were gone,” says Char Rivette, executive director of Chicago Children’s Advocacy Center (ChicagoCAC), a nonprofit organization that responds to reports of child sexual abuse.

Child sexual abuse is shockingly common. One in 10 children will be sexually abused before their 18th birthday, according to Darkness to Light, a national child sexual abuse prevention organization.

Many children are in heightened danger during Covid-19. “Potential victims are in the home consistently with adults who might be the ones who are abusing them,” Rivette says. “In over 90% of cases, the abusers are known to the child and, in many cases, are family members or close relationships to family members, like boyfriends and stepfathers.”

Many parents are essential employees and need to leave home for work, she says. That leaves kids at home with other adults caring for them. Potential abusers have more access and no oversight from mandated reporters.

“To me, that’s a recipe for disaster, because access goes up, likelihood goes up, but that safe place where kids go to school every day is removed,” Rivette says.

During one incident in October, classmates and a teacher witnessed a 7-year-old being sexually assaulted during a break from a remote class. The teacher quickly called the girl’s name, told other students to log off, and contacted the school principal, who called the police and DCFS. An 18-year-oldmale relative has been charged with predatory criminal sexual assault.

“A lot of the teachers who I’ve spoken to are terrified for some of the kids they know,” Rivette says. “They’re afraid that [the kids] are in situations where they’re more at risk and that they don’t have any safe place to go. Some of these kids are living in very challenging homes. At school, at least they had their teacher, their classmates, they got breakfast and lunch. In some ways, it was a respite from a very chaotic home life.”

A push for justice

While the pandemic has impacted domestic violence response, so has the push for police and criminal justice reform.

Domestic violence agencies depend on police to respond to domestic abuse calls and rely on the court system to prosecute those who harm. But there’s a strong call now for non-law-enforcement approaches.

In 2019, the Chicago Police Department (CPD) made 10,095 domestic-violence-related arrests, according to a 2020 “State of Domestic Violence in Illinois” report from The Network.

Although people of all races and ethnicities experience domestic violence, Black people experience domestic violence at a disproportionately high rate. In Chicago, 66% of domestic violence survivors are Black, 20% are Latino, and 12% are white, according to CPD data in the city of Chicago’s first-ever “Our City, Our Safety” comprehensive violence reduction plan, released in September 2020.

“Certainly with the history of violence against people of color by law enforcement in our area, there are many victims who don’t feel safe reaching out to law enforcement. We want them to have someone else who they can reach out to,” says Pyron at The Network. “What we really need is an expansion of community-based services, including a non-law-enforcement community-based-responder model,” she says.

Such a model would include specially trained social workers and community service providers who — in certain, but not all, cases — could act as first responders and continue to work directly with survivors to address the complex emotional, physical, and financial challenges they face.

These community-based advocates would be able to provide “some concrete support that the police aren’t in a position to do, nor should they,” Pyron says. “We need to put the right people in the right positions to respond to the needs of survivors.”

Pyron also says the Cook County court system needs to be more responsive to domestic violence survivors.

“The court is indifferent to the safety and well-being of survivors who petition for relief,” she says. “Throughout the pandemic, they have provided an insufficient response to the needs of domestic violence survivors and have failed to communicate in a clear and direct manner.” The confusing court system is difficult for survivors to navigate without the help of a legal advocate or attorney, she adds.

Initially during the pandemic, most courts suspended operations.

Cook County courts have since reopened, but they are conducting almost all hearings via videoconferencing, with no date to resume in-person services, even though not all individuals have technological access.

After the pandemic started, courthouses in south and west suburban Cook County stopped providing emergency orders of protection — an important court order that protects survivors for up to three weeks. Instead, survivors in Cook County now need to go downtown or to the northwest suburbsto get a protection order, creating inequitable access, Pyron says.

Call for funding

Pyron calls for the city of Chicago to take a public health approach to domestic violence instead of a law-enforcement-only approach. But money, of course, is an issue, especially because the state of Illinois is expected to signifi- cantly reduce funding for domestic violence services in its 2021 budget.

The Network suggests the city of Chicago reallocate $35 million from the police budget — an amount that’s equal to one week of CPD spending — to gender-based violence prevention and intervention.

The money could be reinvested in community-based violence prevention and response efforts, including developing a system of nonpolice responders, Pyron says.

The city’s “Our City, Our Safety” plan outlines several strategies for reducing domestic violence. Its goals — which would need to be funded and actualized — include expanding programs for abusers, improving collaboration between domestic violence programs and gun violence programs, increasing safe housing for survivors through rental assistance programs, and implementing school programs that address teen dating violence.

Prevention and education programs are a priority for child sexual abuse as well. Rivette at ChicagoCAC is a co-founder of the Chicago Prevention Alliance, which is a coalition of some 20 groups that are pushing for sexual harm prevention education in schools and youth organizations.

“I think every student in every school should have comprehensive sexual harm prevention at an individual level, and teachers and parents need it as well,” Rivette says. “As adults, it’s all our responsibility to protect children.”

During the pandemic, it can be harder than ever for a survivor to leave an abusive situation. But despite the challenges, advocates are doing their best to be there for people like Elise and Maya, offering guidance, hope, and a call for change.

Reaching Out for Help

If you’re experiencing domestic violence or concerned about someone you know, reach out to the following organizations. You can also increase awareness of domestic violence by sharing helpful resources on social media.

“Just by posting our phone number, sharing our information, individuals know that we are here,” says Damaris Lorta, of A Safe Place. “You never know who is going to need that number. You may be the one who makes a difference by sharing that information.”

If you’re concerned about someone experiencing abuse, keep connected, says Kesha Larkins at Connections for Abused Women and their Children. “With that increased layer of isolation, you may not hear as often from a friend or family member who might be experiencing domestic violence, but just remaining available, continuing to reach out to them, and being available to provide support is important.”

A Safe Place

crisis line, 847-249-4450 (800-600-SAFE)

Connections for Abused Women and their Children

domestic violence hotline, 773-278-4566

Illinois Department of Children and Family Services

online child abuse neglect reporting,

dcfsonlinereporting.dcfs.illinois.gov

child abuse hotline, 800-252-2873

(800-25-ABUSE)

Illinois Domestic Violence Hotline

call or text, 877-863-6338

(877-TO-END-DV)

National Domestic Violence Hotline

800-799-7233

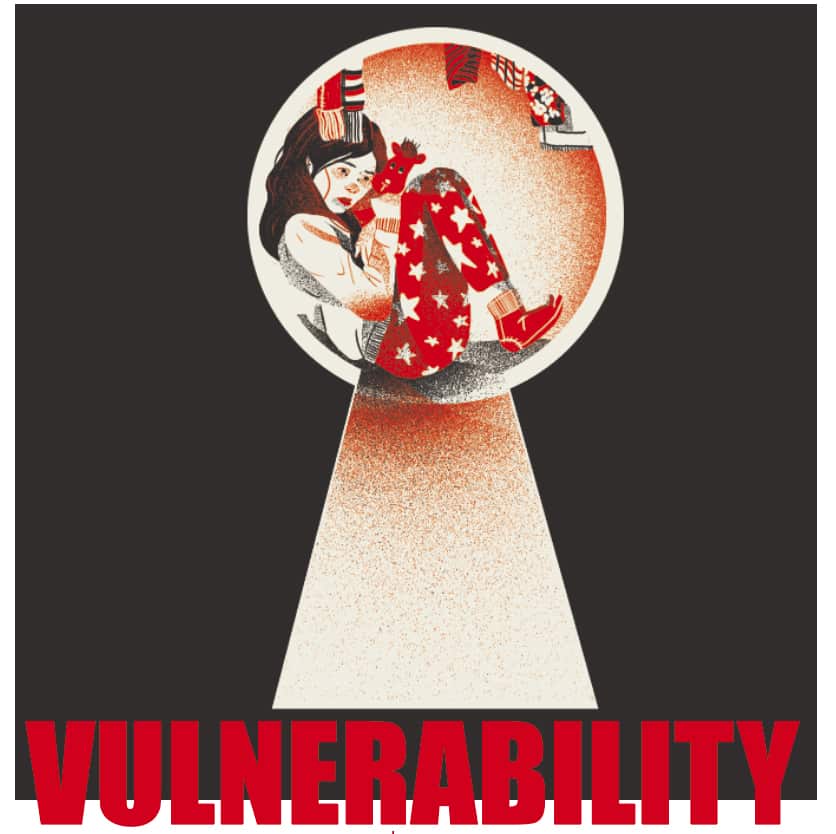

Top illustration by Alessia Damone. Originally published in the Spring/Summer 2021 print issue.

Eve Becker is an award-winning editor and writer. She is the former Editor-in-Chief of Chicago Health magazine and Caregiving magazine, as well as the former Managing Editor of Tribune Media Services. She is a highly skilled communications professional, and has created content for a variety of platforms, including magazines, newspapers, websites, newsletters and nonprofit organizations.