Low-FODMAP diet may help those with stomach ills

Let’s face it, when your gut is not happy, neither are you. Many people struggle daily with abdominal pain, gas, bloating, constipation or diarrhea—all hallmarks of digestive sensitivities or irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). The causes of distress can be hard to determine, but recent research points to a specific group of carbohydrates—some sugars and fibers—that may be the culprit for many individuals.

When specific carbohydrates are poorly absorbed in the small intestine and highly fermented in the large intestine they can cause an array of uncomfortable gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms.

“We basically have a brewery in our large intestine where carbohydrates are fermented,” explains Lori Welstead, MS, RD, LDN, a registered dietitian specializing in gastrointestinal disorders at University of Chicago Medicine. “This is good and is a sign of a healthy gut. But some people with IBS may be exquisitely sensitive to the cumulative effect of some highly fermentable food. This results in gas, bloat, distention, pain and diarrhea or constipation.”

What are FODMAPs?

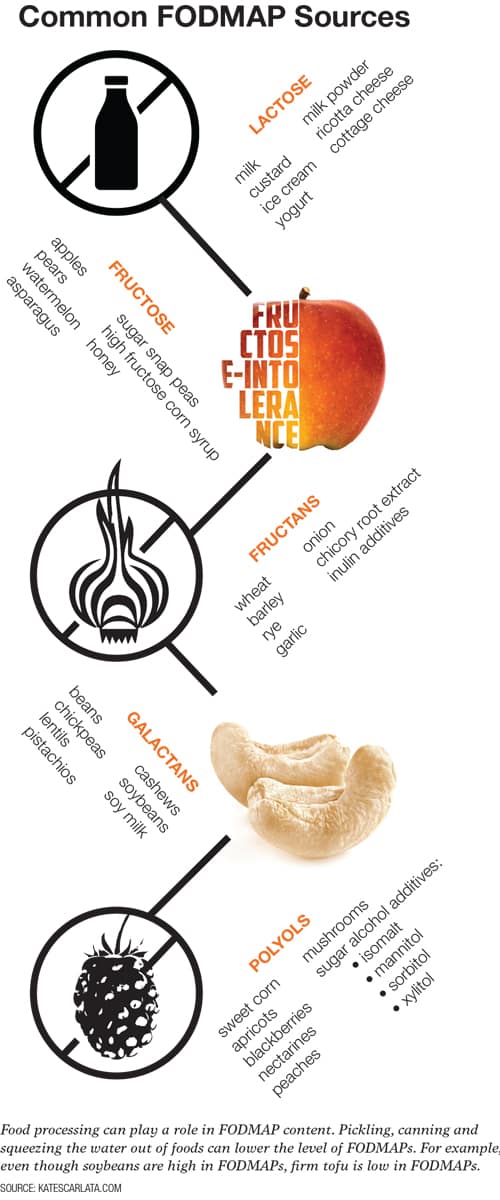

These types of commonly malabsorbed short-chain carbohydrates are classified by an awkward acronym: FODMAP. First coined at Monash University in Australia, FODMAP stands for fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols.

High-FODMAP foods fall into five subtypes: lactose (milk), excess fructose (apples, pears), fructans (wheat, onions, garlic), galactans (legumes) and polyols (blackberries, mushrooms, some sugar substitutes).

Recent research in Gastroenterology revealed that 75 percent of IBS patients gained clinically significant benefits from following a low-FODMAP diet. As a result, it’s increasingly being used by health professionals for patients with IBS and other digestive sensitivities.

At the recent Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics’ Food and Nutrition Conference & Expo (FNCE), the low-FODMAP diet was a hot topic. “A low-FODMAP diet is a tool that we have in our back pockets that can help people with IBS feel better in as little as two days,” says Kate Scarlata, RDN, LDN, who presented two evidence-based FODMAP sessions at FNCE.

“High-FODMAP foods have an osmotic effect, which means they pull water into the intestine and generously feed our intestinal microbes through fermentation, resulting in gas,” Scarlata explains.

For those with a sensitive gut, this combination of gas and water stretches the intestines. Collectively, these side effects can cause pain, cramping, bloating, diarrhea and/or constipation.

A low-FODMAP diet

It’s possible for a person to be sensitive to one FODMAP category and not others, so it’s usually not necessary to eliminate all high-FODMAP foods for the long-term. The diet is not a one-size-fits-all proposition; consulting with a registered dietitian (RD) who understands the issue is important for the best outcome, experts stress.

“There is an art and science to working with the low-FODMAP diet, and the RD has to ask a lot of questions and employ the diet with care,” Scarlata says. “Based on a patient’s clinical profile (i.e., IBS with constipation and/or diarrhea) it is possible that the diet can be tailored and foods to eliminate can be cherry-picked so he or she doesn’t have to give up everything.”

Finding out what FODMAPs you are sensitive to starts with an elimination diet. For two to six weeks, all high-FODMAP foods are taken out of the diet. Once symptoms are under control, each category of foods is systematically reintroduced to determine which ones trigger GI symptoms.

“I ask my patients what foods they miss the most, and then we slowly add foods back in by group. However, it’s typically not just one food that is causing symptoms, but a cumulative effect over the course of the day,” Welstead explains. The more troubling foods you eat, the worse you will feel. Imagine a bucket that overflows when it is full of foods that you cannot tolerate.

The goal is to initially eliminate food triggers but then to reintroduce the foods you can tolerate, as some FODMAP foods contain beneficial fiber and prebiotics, which feed good bacteria. Decreasing FODMAPs in the diet can affect the delicate gut balance, as many high-FODMAP prebiotic foods are helpful.

“Foods high in FODMAPs feed good microbes in the gut, therefore it’s important to use this diet as a short-term therapy and reintroduce tolerable carbohydrates back in as soon as possible,” Welstead explains.

The FODMAP story is still unfolding, but it has proven to be a great sense of GI relief for many people around the globe.

Victoria Shanta Retelny, RDN, is a lifestyle nutrition expert, author of Total Body Diet for Dummies and creator of the blog, SimpleCravingsRealFood.com.

Originally published in the Spring 2017 print edition