Increased innovation in growing cartilage is slowly changing knee repair

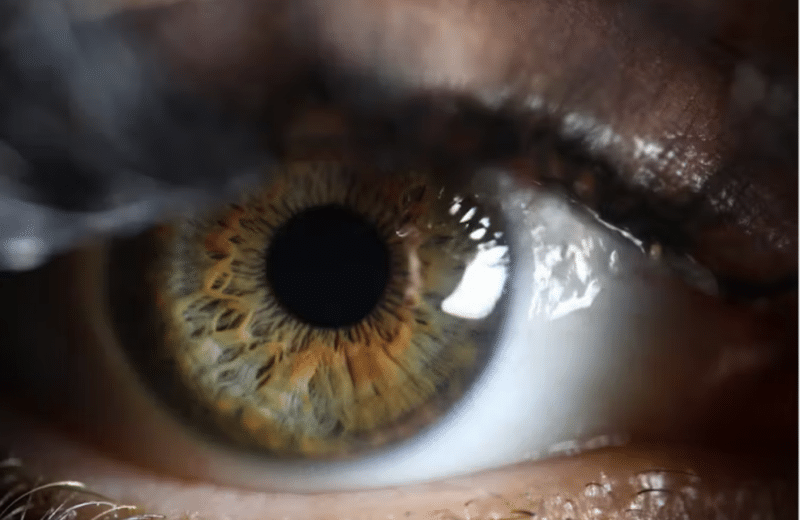

Our knees are undoubtedly the most important joints in the human body. They connect the upper and lower leg together and make it possible to bend and rotate our legs, allowing agility, mobility and functionality.

They also happen to be the body’s largest joint, if that helps their case. Wear and tear on the knee joint causes damage that may impact one’s physical performance. We often see it in sports: Players tear their ACL, MCL and meniscus and suffer other knee-related injuries. But damage to the knees can affect the rest of us, too, and hinder the most routine of daily activities.

Chicagoland native Meaghan Kirkpatrick knows better than most just how important her knees are. She has dealt with poor knee stability since age nine, as her knees would often pop out of the sockets and buckle underneath her. “My functioning was fine, but when they’d sometimes pop out, it would take a while for them to go back in,” she says. “I’d have to make sure I had a brace with me at all times, especially during gym class.”

Kirkpatrick saw a physician in July 2014 after she thought she broke her leg falling down a flight of stairs. She didn’t break her leg, but the physician noticed she had no cartilage in her left knee and that both knees were out of their sockets. Kirkpatrick was then sent to Jason Koh, MD, director of the NorthShore Orthopaedic Institute, who said she needed surgery.

Cartilage damage of the knee joint comes in varying severities, ranging from Grade I to Grade IV; IV being the most severe. Knee specialists and orthopedic surgeons strive to innovate new procedures that lead to faster, more efficient results.

Kirkpatrick had an autologous chondrocyte implantation, a two-stage procedure during which the damaged cartilage is biopsied and then tissue is grown in a lab for several weeks. Once cultivated, the lab-grown cartilage is placed back into the patient’s knee. The procedure has been around since 1994 and is still limited, says Ronak Patel, MD, orthopedic surgeon at Hinsdale Orthopaedics. While results have been promising, he says that the technique continues to evolve.

“In the initial technique, lab-grown cells were injected under a tissue flap and sealed,” Patel says. “Since then, the technique has been modified by incorporating various collagen membranes to further promote hyaline cartilage repair tissue and prevent adverse events occasionally seen with first-generation techniques.” He says researchers and orthopedic surgeons are continuously working to modify the procedure in order to optimize outcomes.

The procedure is still new and is being adjusted, Koh says. “We are investigating new procedures that can potentially reduce the recovery time and improve outcomes,” he says. “We’re also exploring ways to increase the number of patients who benefit from this procedure.”

Recent studies suggest autologous chondrocyte implantation offers better long-term promise compared to microfracture procedures, the more common procedure for repair of knee cartilage damage, Patel says. Microfracture procedures use an awl to make perforations in the bone near the damaged cartilage. These holes then release cells that create new cartilage-like tissue.

“Early promising results have been reported by European studies looking at even newer-generation techniques and are paving the way for similar high-quality studies in the United States,” says Patel. “There is no miracle cartilage implant just quite yet, but we have some good treatment options.”

Clinical trials of new methods for the procedure are occurring; one is presently in the phase-three evaluation stage and is expected to be ready for use in the near future. The subject: a new proprietary implant called Neocart. Researchers and surgeons predict that, if successful, Neocart may make big strides toward a healthier knee joint postsurgery. Patel says it’s too early to determine the impact it will make.

The goal with cartilage restoration, Patel explains, is to reform hyaline cartilage at the defect site. One of the techniques in the works to do so is using a 3-D scaffold.

“Neocart has an innovative processing component to it as well as a three-dimensional scaffold that may promote better and longer-lasting hyaline cartilage,” Patel says. “The centers that are investigating this implant are engaged in a multicenter randomized controlled trial. This is important as we want high-quality evidence to support our clinical decisions and procedures.”

Patel says patients who qualify for autologous chondrocyte implantation can get precertified with their insurance carriers to see whether they’re covered for the procedure. Once certified, patients’ insurance agreements determine the final expense.

Kirkpatrick’s autologous chondrocyte implantation was on Christmas Eve 2014. Although skeptical at first, she hasn’t regretted it for a second. “My functioning is better,” she says. “I don’t have to worry about my knees popping out anymore. I can walk, jump or hobble if I wanted to.”

So who qualifies for an autologous chondrocyte implantation? Patel says ideal candidates are usually less than 40 or 45 years of age, have a body mass index of less than 35 and have an intact joint. Koh says that patients with arthritis of the knees, however, aren’t the best candidates because a fully biologic knee replacement isn’t possible at the moment. “We are exploring other regenerative medical procedures such as growth factors and stem cells to help these patients,” he says. “So far, this procedure is able to fill in large potholes but can’t resurface the driveway, so to speak.”

Once the surgery is complete and recovery takes its course, most patients, if not all, can return to their previous levels of activity, Koh says. Even an athlete can return to the skill level he or she was previously at, he adds.

Getting in touch with a specialist is a must if you’re suffering from knee issues, let alone cartilage damage. Kirkpatrick says anyone skeptical about the surgery, as she was, should go into it with positivity. “I wondered at first [whether] it was necessary and worth it. Now after having it, I know it was worth it,” she says.“I’d rather have the surgery than live the rest of my life with bad knees.”