Advancements improve outlook for people with blood cancer affecting the bone marrow

Human resources manager Valarie Traynham was standing in front of a group of new hires when her nose started bleeding. She stepped away briefly, but when the nosebleed lasted for more than an hour, she grew concerned and went home sick.

“I had a history of anemia, so I thought maybe I needed to increase my iron uptake,” the 49-year-old Aurora resident says. Soon after, she caught the flu, accompanied by severe fatigue and unexplained back pain. A round of lab tests revealed high protein levels in her blood.

Her doctor referred her to a hematologist, who ordered a bone-marrow biopsy. “Is it my anemia acting up?” Traynham asked. The answer she received was completely unexpected: “It’s cancer. It’s an incurable cancer.”

The hematologist diagnosed Traynham with myeloma, a blood cancer that causes abnormal immune plasma cells to grow in the bone marrow. When myeloma grows in multiple areas of the body, as it typically does, it’s called multiple myeloma.

An internet search told Traynham she had three to five years to live. That was seven years ago, and she’s still going strong.”

In fact, new advances are helping many people with multiple myeloma live disease-free. While there’s still no cure, doctors now often consider it a chronic disease, manageable over the long term.

What is multiple myeloma?

Myeloma is a blood cancer that affects cells in the bone marrow. Cancerous plasma cells produce abnormal proteins instead of normal antibodies that fight off invaders. This makes it difficult for people to fend off or recover from infections.

Most myeloma symptoms — kidney failure, anemia, and high calcium levels — are only visible on laboratory tests, but signs also include immobility, fatigue, shortness of breath, lingering infections, and nosebleeds. As abnormal plasma cells grow in the bone marrow, they form masses that disrupt the bones’ structure, commonly leading to pain in the ribs and back.

Multiple myeloma accounts for almost 2% of all cancers and 19% of blood cancers in the United States. It more frequently occurs in people over age 65.

Each year over 34,000 new cases are diagnosed in the U.S., and more than 12,000 people die of the disease, according to Syed Ali Abutalib, MD, who is Traynham’s physician and co-director of the hematology, bone marrow transplant (BMT)/cellular therapy program at Cancer Treatment Centers of America (CTCA) in Zion.

The disease is twice as common — and twice as deadly — in Black Americans compared to white Americans, according to the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation. The difference may partly be due to unknown underlying genetic factors, as well as racial healthcare disparities.

What once was considered a disease with a low survival rate is changing.

Andrzej Jakubowiak, MD, PhD, director of the University of Chicago myeloma program, no longer sees multiple myeloma as incurable. The five-year survival rate was 53% in 2016, and new treatments — the result of years of research and clinical trials — are increasing that rate,

New therapies for multiple myeloma

“We’ve been making tremendous progress over the last 20 years,” Jakubowiak says. Multi-drug treatments, combined with antibodies, are creating a strong response, with disease no longer detectable in a majority of people.

Treatment often involves high-dose chemotherapy to kill the cancerous myeloma cells, followed by a stem cell transplant. The onerous process knocks out a person’s immune system in an effort to reboot it.

“These new immunotherapies are already making a difference.”

University of Chicago researchers are working with pharmaceutical companies to develop new classes of treatments. For example, in CAR T-cell immunotherapy, specialists extract T-cells — a type of immune cell — from a person’s body and engineer them in the lab to target malignant myeloma cells. After being infused back into patients, these designer CAR T-cells engage the immune system to eliminate myeloma, plus they remain in the body like living drugs.

In another new immunotherapy treatment, specialists infuse or inject a type of antibody called bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE) antibodies into patients weekly. One part of the antibody attaches to the tumor cell; the other activates immune cells. The treatment engages the individual’s immune system, leading to effective elimination of myeloma.

“These new immunotherapies are already making a difference and will undoubtedly further improve treatment outcome in all stages of myeloma,” Jakubowiak says.

At the University of Chicago, myeloma researchers are examining demographic disparities to help more people in the Hyde Park area with access to care, treatments, support, and cutting-edge research into possible genetic causes. “We are proud that we can help our patient population living in Hyde Park in this way,” Jakubowiak says.

Value of support

When Traynham first started treatment, her white blood cell count plummeted. She was so weak and fatigued that her doctor admitted her to the hospital. “At that point, I was really scared. I didn’t have my family there. It was just a tough time,” she recalls. “The only thing that kept me going was my faith, and it keeps me going to this day.”

After she connected with CTCA, doctors recommended a stem cell transplant. By then, she had support. Two friends used vacation time to stay by her bedside, and family members flew in to boost her spirits. “That just warmed my heart,” Traynham says.

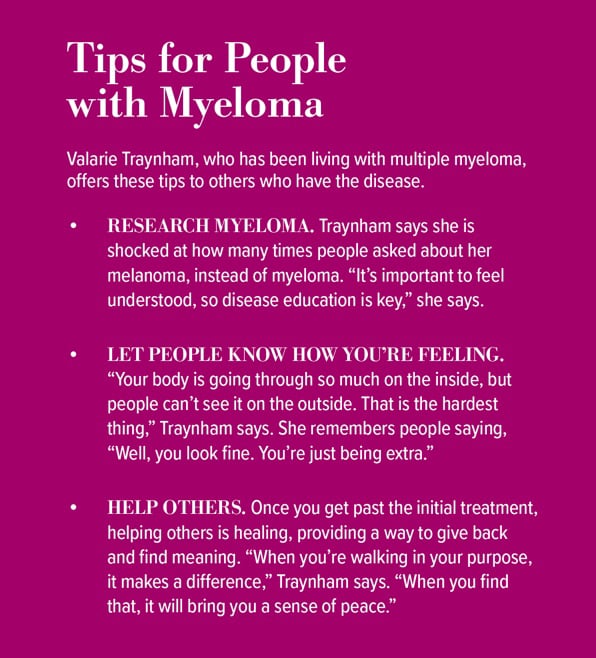

Meanwhile, she attended support groups, eventually leading her local group and finding her calling: to help others with multiple myeloma. She met new friends who were 10- and 20-year myeloma survivors.

“These people were thriving,” says Traynham, who also battled breast cancer in 2019. “I thought, ‘I want some of that.’” Soon, she became a myeloma coach with Myeloma Crowd, a division of the nonprofit HealthTree Foundation.

Outsiders don’t always understand the toll of myeloma and its treatment, so individuals don’t always get the support they need. Traynham aims to fill this gap. “I wanted to help those in my situation who didn’t know where to turn,” she says. “I really found my purpose in all of this. It brings me great joy.”