Pulmonary critical care physician finds solace through art during the Covid-19 pandemic

In the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, Justin Fiala, MD, was feeling whiplash. He split his time between quarantine at home and seven-day stretches in the medical intensive care unit (MICU) at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. As a pulmonary, critical care, and sleep specialist, he was working up to 14 hours a day, treating the sickest of the sick during a time when nobody had a grasp of what Covid-19’s toll would be.

“We were going 120 miles an hour, and then I’d get home, and it was 0,” Fiala says.

Once home, with everything shut down, Fiala sat with a mix of complex emotions, among them grief, frustration, and fear for his colleagues in the hospital. He saw people die daily, separated from their families. And he watched society turn from treating healthcare workers as heroes to villainizing them. He needed an outlet.

“We had people who you could see the anger in their eyes up to the very end. Their lungs were failing because of Covid, and they hated it,” Fiala says.

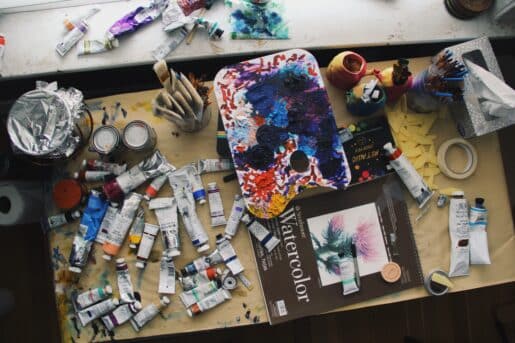

And then, as many people did during the heart of the pandemic, Fiala rediscovered long-lost interests. For him, it was art.

“I had all of my canvases and brushes, so I could just pick it up,” Fiala says. The degree of catastrophe removed a barrier.

At his home studio in Lakeview, Fiala put on the soundtrack for the contemporary opera Nixon in China, placed a canvas on his easel, and began pulling from the decade he spent studying at the Village Art School in Skokie.

At first, Fiala filled the canvas with abstract color fields. A blue-toned figure eventually emerged on one side of the canvas, caught in a tangle of wires. The person was on ECMO — a heart-lung bypass machine that keeps people alive who otherwise wouldn’t be able to breathe on their own.

Fiala realized he was painting his patients but also himself — tethered and trapped within modern medicine’s promises.

“It’s a meditation on the patient experience, on the ramifications of what we do — intubated and capitulated,” Fiala says. “There’s a healthy understanding in critical care that what we do can be harmful. But we do what we do because we believe we can bring people back from the brink.”

As the weeks ticked by, Fiala took up 3D printing, devising plans for sleep apnea masks. He also printed dozens of colorful lungs, which he gives to medical residents as gifts when they graduate.

The 3D printing, Fiala says, helped inform the shape his paintings took. He went on to paint other pieces over the next year: a surgical mask hanging from the fingers of a peace sign; healthcare workers sitting solemnly on a city bus, reflecting on or preparing for the day; a smiling self-portrait, in his blue scrubs and red-framed glasses.

The works were featured recently at TEDxChicago’s annual event at the Harris Theatre. Johnathan Prunty, lead host and partnerships director for TEDxChicago, says event organizers were drawn to Fiala’s work because it “captures the talent that we have here in our own backyard. It’s significant of who he is as a person and what he represents.”

To Prunty, as devastating as Covid-19 was, it also offered an opportunity for people to reset. He says he saw that reflected in the artists featured in TEDxChicago this year. During the pandemic, he recalls, “we were so isolated. You couldn’t go out, couldn’t talk to anyone, had to wear masks. What’s a better way to become yourself than to truly express yourself by whatever means?”

Fiala and some of the other artists featured at TEDxChicago used the pandemic to unleash a different side of themselves. “They had time to sit and think. Who knows how that would’ve come to fruition,” Prunty says. “That’s an expression we want displayed because 8 billion people went through Covid. These artists were able to express themselves even through the mask and the isolation.”

As the pandemic’s demands ebbed, Fiala added another position in the post-acute care unit at the Shirley Ryan Ability Lab. There, he guides patients through recovery from severe injuries.

It’s a powerful counterpoint to the intubated patients he saw during the height of the pandemic. “Like with spinal cord injuries where people have lost a lot of autonomy — I get to come in as a pulmonary doctor and [tell them], ‘You can’t move your arms and legs, but I want to get your voice back,’” Fiala says.

Fiala knows exactly how empowering self-expression can be. Still, he says, it may not be enough to carry him through another pandemic. “If the next pandemic comes and I’m still in this role, would I stick it out? I don’t know if I would,” he says.

In the meantime, his paintings offer a glimpse into life during the pandemic, and a side of life that most people find comfort in knowing is there, though they hope to never experience themselves.