The rise in mental health issues and what parents can do

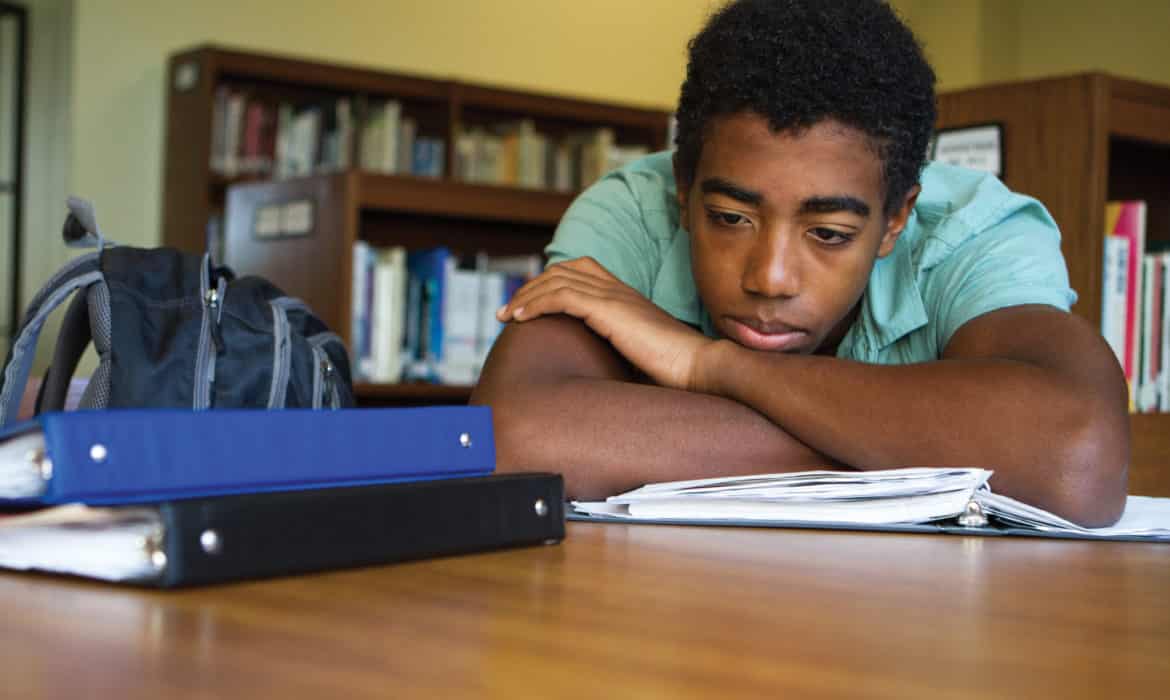

Fifteen-year-old Evan Wilson likes to play video games, draw and listen to music, especially classic punk (think Sex Pistols and The Clash). He’s also dealing with mental health issues — in his case, depression with a mood component and ADHD.

Many teens experience symptoms of depression, anxiety, mood disorder or other mental health issue. The incidence of teen depression in particular is quite serious — and it’s rising.

In 2016, about 12.8 percent of adolescents age 12 to 17 had at least one major depressive episode during the past year — that’s 1 out of every 8 teens. Five years earlier in 2011 the rate was 8.2 percent, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Evan was diagnosed with depression at an early age. “[He] has always been a melancholy kid,” says Connie Wilson, his mother. “I thought that was part of his temperament.” When he was 8, though, Evan told his mother that he was “tired of feeling sad all of the time” and she decided to seek treatment for him.

After being evaluated, Evan received cognitive behavioral therapy and medication, which has been effective for him. In February 2018, though, he had a major depressive episode. He told his mother that he was feeling suicidal and that he was afraid he might act on his feelings.

After five days of inpatient treatment and several weeks of outpatient treatment, Evan was back at school. “I feel like I’m definitely capable of managing my own mental health from here on out — but it’s hard to do without help from friends and family,” he says today.

Many of today’s teens struggle with mental health issues, too afraid to talk to their parents or even their friends about their emotions and symptoms. But what’s going on, and how can parents help?

More pressure + more isolation

One in 5 adolescents has, or will have, a mental health issue, and the rate of teen depression has increased significantly over the past 10 years, says Eric Nolan, MD, medical director of psychiatry at Northwestern Medicine Delnor Hospital and Northwestern Medicine Behavioral Health in St. Charles. “Between 2005 and 2014, there was an increase from 8.7 to 11.3 percent in major depressive episodes,” among adolescents aged 12 to 17, Nolan says.

A major factor? Cell phone usage, which has led to decreased interpersonal communication and greater isolation among teens, Nolan says. The more hours teens spend on their cell phones, the more likely they are to experience depression and suicidality — five hours a day of cell phone use makes a teen 71 percent more likely to be depressed.

Kids are also under more pressure from parental, teacher and peer expectations. “The number one thing I have noticed with children and adolescents today is that they are experiencing difficulties managing daily stressors and struggling to use healthy coping strategies,” says Jackie Rhew, LCPC, clinical liaison for child and adolescent services for AMITA Health Alexian Brothers Behavioral Health Hospital in Hoffman Estates.

“We’re seeing a generation of kids who aren’t as resilient as they were 10 years ago,” she says. As a result, kids are more likely to turn to unhealthy coping strategies such as avoidance, substance use, self-injury and disordered eating.

Teen angst

Any parent of teens knows that mood swings and drama come with the territory. So how do you distinguish between normal adolescence and what may be signs of a mental health issue?

Teens may not exhibit the same symptoms that adults do, says David H. Baron, MD, medical director at Yellowbrick, a national psychiatric center in Evanston that specializes in treating adolescents and young adults with mental health and substance abuse issues.

“Often the initial signs are some decline in some areas of function, whether that’s academics or social withdrawal,” he says. That may mean a sudden drop in grades for an otherwise solid student or a previously connected teen dropping her friends.

The big factor to consider is time, says Bryn Jessup, PhD, director of family services and systems at Yellowbrick. “Adolescents are known for their mood swings and irritability,” he says. “What you’re looking for is [a time of] beyond a couple of weeks — four to six weeks is my rule of thumb.”

Advice for parents

It’s important to keep an open dialogue with your kids. “Communication is key,” Nolan says. “Start moving these conversations about mental health forward even before your kid has a problem so you’re not being reactive but proactive.”

Helping kids develop healthy ways of handling day-to-day stressors can also help them develop greater resilience. “We work with children and their parents to teach healthy coping strategies, as well as teaching them to sit with the distress and learn to be comfortable being uncomfortable,” Rhew says.

Managing your own expectations is key, too. If you explode over your teen’s radical haircut, she may be less likely to open up to you. “Part of the developmental task of being an adolescent is figuring out how to be different from your parents,” Baron says. “Have some flexibility as to how you respond to your teen’s efforts to establish this independence.”

If you are concerned about your child’s mental health, talk to his or her pediatrician or school social worker and get a recommendation for a specialist who works with adolescents, Nolan says. If your child receives a diagnosis of a mental health disorder, treatment may include counseling, medication and coping strategies like meditation.

Early intervention can help your teen get the appropriate treatment and help him, like Evan, gain the confidence that he needs to manage his condition. (Note: If you feel that you can’t keep your child safe, even with appropriate supervision, call 911 or take your child to the emergency room.)

The most important thing that parents can do for kids, Baron says, is to stay connected even during the trials and tribulations of the teen years.

Baron calls the imposition of authority irrespective of the teen’s point of view “outside-in” thinking. On the other hand, an “inside-out” approach attempts to understand a teen’s thoughts.

“Rather than outside-in thinking, I encourage parents to establish relationships with their children,” he says. “Work on communication and provide a safe space so that [your] son or daughter can describe what they’re going through.”

The bottom line? Trust your instincts, Wilson says. “You know what is typical and not typical for your kid. It doesn’t matter that teens are moody — if you think this is beyond moody, follow your gut.”

Teen Mental Health Statistics

- In 2015, 40% of high school girls and 20% of high school boys showed symptoms of depression.

- In 2016, 12.8% of adolescents age 12-17 had at least one major depressive episode in the previous year.

- In 2017, 17.2% of high school students said they seriously considered attempting suicide in the previous year.

- In 2017, 7.4% of high school students said they attempted suicide one or more times in the previous year.

- Suicide is the second leading cause of death among people ages 10-34.

Sources: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, National Institute on Mental Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention