Chicago faced severe health inequities long before Covid-19. Whose job is it to solve the problem?

It was probably the flu, but Jontay Darko’s grandmother wasn’t going to take risks. She rushed Darko to Mercy Hospital & Medical Center on the Near South Side and pleaded for a doctor to see her. This was the 1990s. The family didn’t have health insurance, but their unease went deeper than that.

“My grandmother was so worried because my brother had passed away years before from complications of mumps,” Darko says.

The experience was formative for Darko. This, plus other interactions with a struggling healthcare system, fueled her drive to become a doctor.

Growing up, she had helped care for her grandmother, picking up medications from the community hospital’s pharmacy and accompanying her to the overcrowded emergency room where people didn’t have enough places to sit. “That was always a catastrophe,” Darko says. “Why were there people on canes and crutches waiting in line for hours?”

Even as a teen, Darko thought, “There’s got to be a better way.”

Darko received her medical degree and began her residency in family medicine in July at the University of Illinois at Chicago. But she never anticipated that she would start during a pandemic that had torn through Black and brown communities on the South and West sides.

Covid-19 was reinforcing lessons Darko had seen play out her entire life, throwing long-standing health inequities into stark relief.

She recalls early on when people called Covid-19 “the great equalizer” — a virus attacking everyone indiscriminately.

“It didn’t take long for us to realize that wasn’t the case,” Darko says. “Like most things that happen, people of color and those with lower socioeconomic status are most affected.”

In Chicago, Black people accounted for 70 of the first 100 recorded Covid-19 deaths, according to the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office, despite making up only 30% of the city’s population.

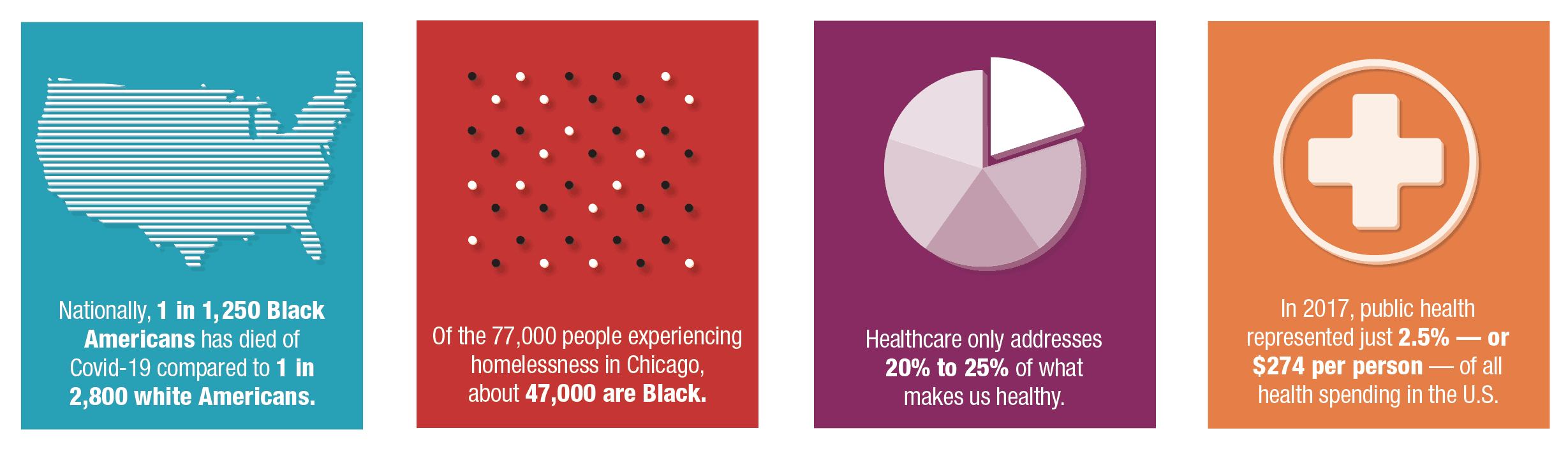

As the pandemic unfolded, city data revealed that Latinos have the highest Covid-19 infection rates, while Black people have the highest death rates. Chicago isn’t an outlier in these disparities. Nationally, 1 in 1,250 Black Americans has died of Covid-19 compared to 1 in 2,800 white Americans as of early August, according to the APM Research Lab, a nonpartisan research group.

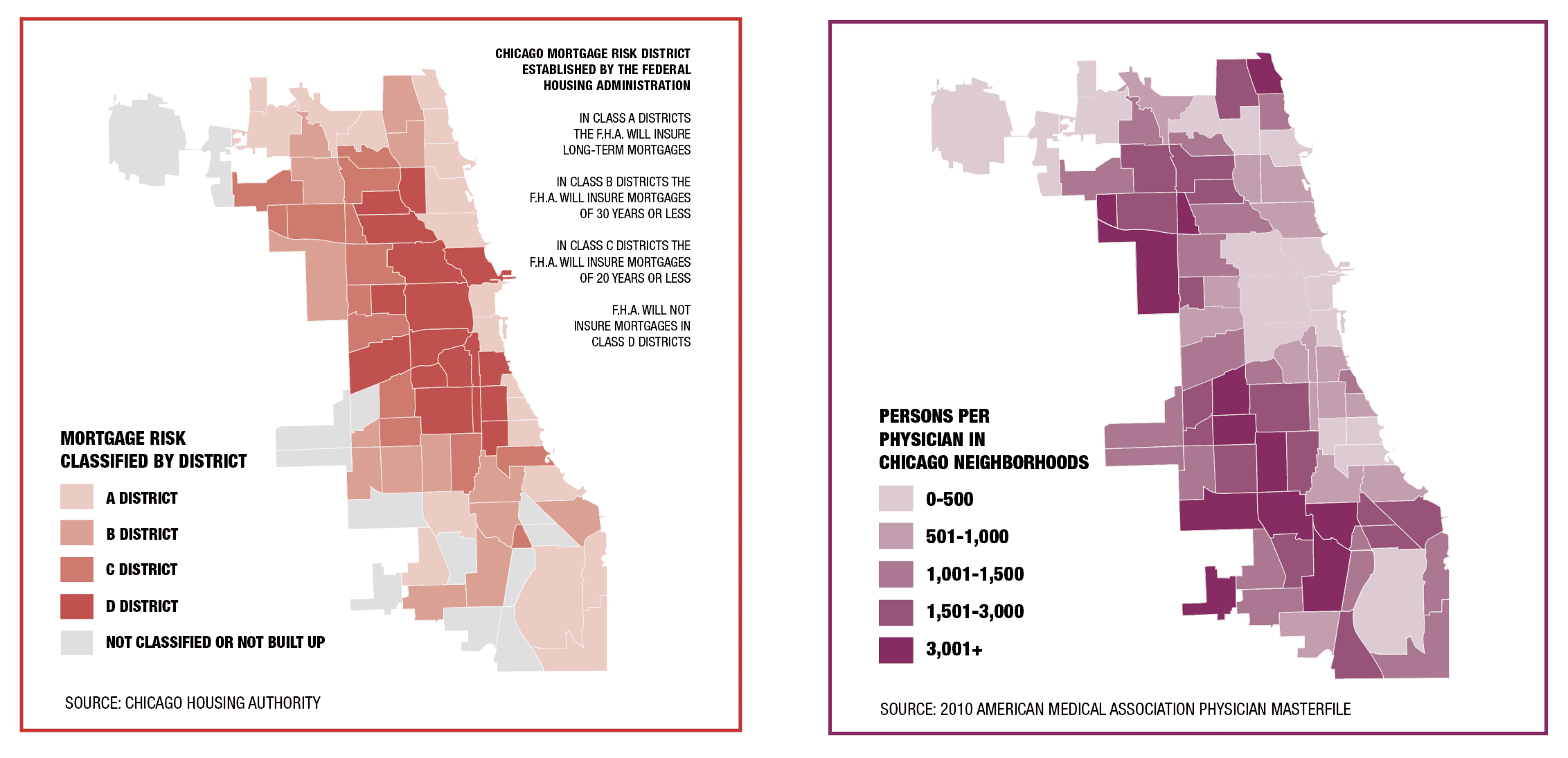

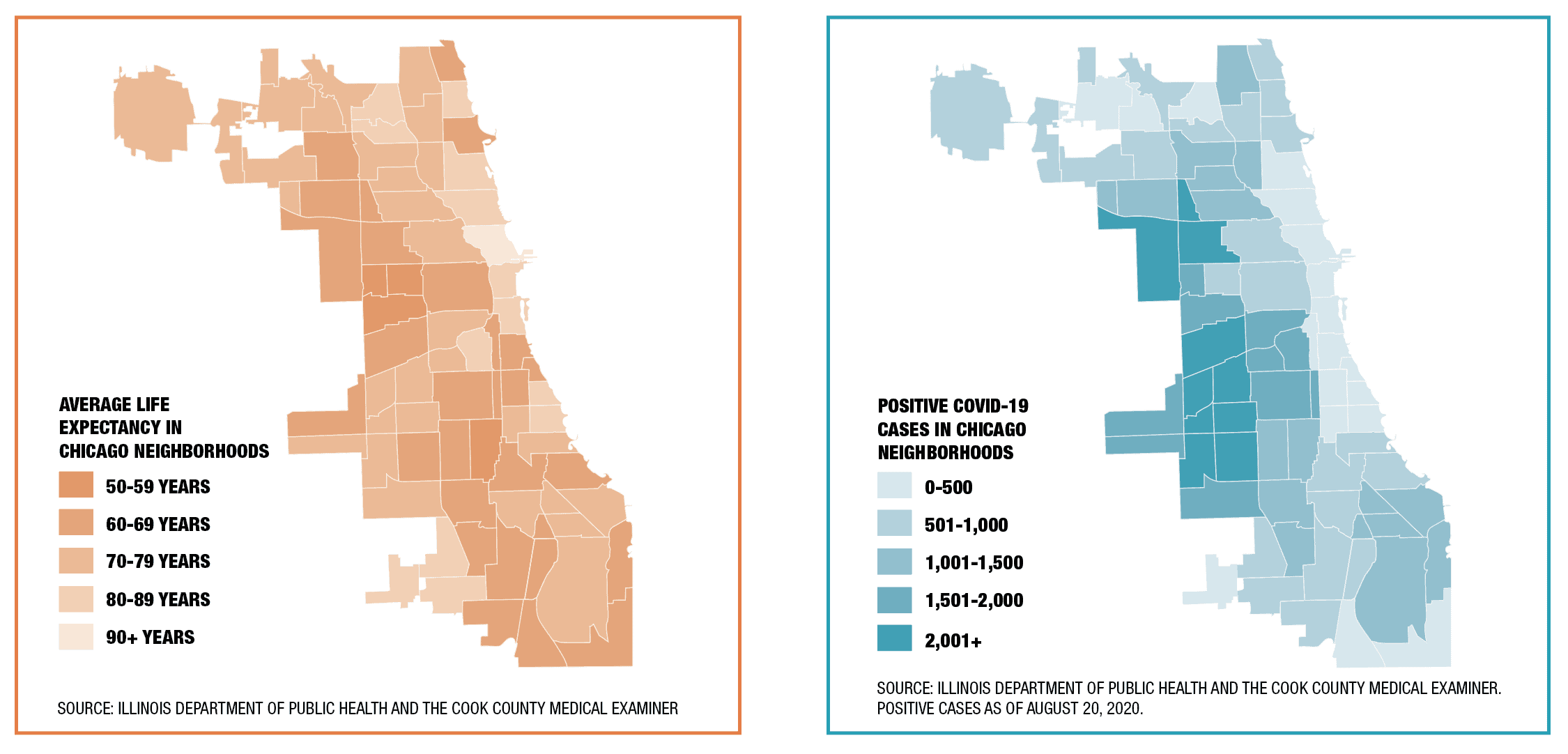

But health disparities troubled Chicago long before Covid-19. There’s a large life expectancy gap between predominantly white neighborhoods such as Streeterville (life expectancy: 90 years) and Black neighborhoods such as West Garfield Park (life expectancy: 68 years), according to 2015 data from the City Health Dashboard.

Racism shows up in doctors’ offices, too. Nearly half of medical students surveyed believed that Black people have thicker skin, faster-coagulating blood, and/or less sensitive nerve endings than white people, according to a 2016 study in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science. Trainees who believed that Black people were less sensitive to pain were less likely to treat the pain adequately.

Such discriminatory beliefs impact the way doctors respond to Covid-19. “If I say I can’t breathe, I’m short of breath, you send me home, and I die — that’s happened too many times,” Darko says. “It’s not a coincidence.”

She adds, “That’s why it’s important for people of color to become doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists. It’s important to be treated by someone who understands you culturally as a means to provide more effective care.”

That raises the question: Whose job is it ultimately to fix these disparities? Historically, that responsibility fell to the government. But as government has evaporated from public spaces in recent decades, private businesses, nonprofit organizations, and community groups have had to fill in the gaps. Are they enough?

Health factors

Before deciding who solves the issue, consider how we got here. Like Darko, internal medicine physician David Ansell, MD, MPH, also uses his life experiences to inform his work. His mother’s side of the family was wiped out in the Holocaust. “But in this country, I had all this privilege and access. It was my skin color and my Y chromosome,” says Ansell, senior vice president for community health equity at Rush University Medical Center.

In Ansell’s 2017 book, The Death Gap: How Inequality Kills, he writes, “Where you live dictates when you die. … People who live in those western suburbs and on the Gold Coast live significantly longer than the people in the struggling neighborhoods in between. A 20-minute commute exposes a near 20-year life expectancy gap.”

Drive through those struggling neighborhoods, and you’ll see outward-facing inequities: shuttered schools, lack of public transit, fast food drive-thrus in place of grocery stores, and payday loan chains instead of banks.

Community, economic, and educational factors such as these are known as social determinants of health.

“Healthcare only addresses 20% to 25% of what makes us healthy. The rest is food, safety, secure housing, solid mental health, reduction in stress, exercise,” says Ed Stellon, executive director of the anti-poverty nonprofit Heartland Alliance, which operates health clinics in Chicago’s Englewood, Greektown, and Uptown neighborhoods.

Other health factors are harder to see: type 2 diabetes, heart disease, mental health issues, and trauma.

Often, those chronic health problems stem from the body’s stress response, which in short bursts benefits survival. When that response never shuts off, though, it can lead to chronic diseases and premature aging. In people who feel threatened or feel like they don’t have control, the adrenal glands release cortisol, which floods the bloodstream with glucose, increases the heart rate, and raises blood pressure.

These external and internal health conditions strike Black communities extra-hard. The anxiety of insecurity and the stress of racism create the perfect internal storm for deterioration.

Women’s pregnancy outcomes illustrate the effects. Black women are three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy than white women, according a 2017 study published in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology. They’re also more likely to go into labor early and have low-birth-weight babies.

Two pivotal studies from 1997 and 2002 show that Black women in Africa have the same birth outcomes as white women in the U.S. Once an African woman moves to the U.S., though, within one generation those outcomes fall to levels of Black women’s outcomes here.

To the extent that most white people are aware of these statistics, they often blame the problem on Black people’s personal choices, not realizing that decades of public policies and societal disinvestment have led directly to these health disparities.

But Covid-19 has laid these disparities bare, hitting communities so hard that the situation finally made headlines. These racial inequities are complex, with no easy solution. But they still need solving.

Roots of disparities

Key conditions cause Chicago’s neighborhood life expectancy gap: heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, infant mortality, homicide, opioids, and cancer, according to West Side United, a community-based collaborative.

However, “This isn’t just about the five things that show up on the death certificate the most, but what drives those,” says Allison Arwady, MD, MPH, commissioner of the Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH).

Digging for the root of health disparities in this city divulges, among other issues, the insidious practice of redlining — the government-sanctioned denial of financial services to specific neighborhoods.

For decades, the Federal Housing Administration’s underwriting manuals instructed banks to “prohibit the occupancy of properties except by the race for which they are intended.” Once a neighborhood was redlined, potential Black homebuyers couldn’t get loans. As a result, of the $120 billion in federally guaranteed mortgage lending between 1934 and 1962, 98% went to white families.

During this time, real estate speculators would panic white homeowners by telling them their property values would soon drop and convince them to sell their homes at rock bottom prices. Because Black homebuyers couldn’t get bank loans, agents would sell them homes at sometimes double the price using predatory housing contracts, without mortgage protections.

The Fair Housing Act of 1968, as well as the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act and Community Reinvestment Act of the 1970s, outlawed racist lending practices. But neighborhoods had already polarized, and many remain food and economic deserts. Even today in Chicago, JP Morgan Chase came under fire when data revealed that of the financial institution’s $7.5 billion in home loans between 2012 and 2018, only 1.9% went to Chicago’s Black communities.

In searching for a root cause of these inequities, Ansell shares a fable in his book, The Death Gap. A doctor’s patients keep coming in with broken legs. Each explains they had fallen in a hole in the road. Eventually, “The doctor grabs a shovel, leaves his office, and fills up the hole in the road,” Ansell writes.

That hole in the road has a name, Ansell says: “racism, place-ism.”

Often, calling it out makes other white people uncomfortable, he says, because they have “benefited from a system that has advantaged them while disadvantaging others. That’s tough to say. It goes against meritocracy in this country.”

Most physicians, though, don’t go looking for a cause for the health issues they see every day.

“A lot of doctors see this pain and suffering,” Ansell says, but to absorb it would make getting through a single day impossible. “You have to compartmentalize to get through. To really get to the underlying conditions that are making people sick in this country requires time, insight, and decompartmentalization.”

Public health’s response

That’s where public health departments can help. “Public health’s sweet spot is in that prevention space,” Arwady says. “I hope Covid-19 has raised people’s awareness of public health in general. Before this, a lot of people didn’t even know what public health was.”

A lot of people in recent decades, anyway. Through the early 1990s, people had more frequent interactions with public agencies across the board. Health departments were significantly better funded and played a strong role in disease prevention, environmental health, and emergency planning, such as undertaking a mass polio inoculation program in the 1950s.

Still today, public health workers carry substantial responsibility — just not as robustly as they once could. They prepare for and lead emergency responses; develop health policies; conduct community research; promote and educate about healthy behaviors; report on disease outbreaks; and monitor air, food, and water quality.

In the battle against Covid-19, a stronger public health system would be better able to offer preventive measures, such as providing masks and coronavirus tests, and protect citizens through robust social distancing enforcement and contact tracing. But that response requires people-power, which in turn requires funding.

In 2017, public health represented just 2.5% — or $274 per person — of all health spending in the U.S., according to the nonprofit Trust for America’s Health.

Just a few decades ago, people commonly visited community health clinics for free vaccinations and checkups, whereas now, private companies fill that role. Until the ’90s, CDPH had 2,000 employees. Now the staff is down to around 500 — a shift reflected in health departments nationwide, although many health departments are increasing their staffing to conduct more Covid-19 outreach, says Barbara Norman, PhD, past president of the American Public Health Association’s Black Caucus of Health Workers.

But today, when Covid-19 struck, the local and national public health response wasn’t as strong as it needed to be. If there had been more robust public health departments to deploy when Covid-19 initially hit Chicago, we could be living a much different reality today.

Norman served as CDPH deputy commissioner during a better-funded era, from 1983 to 1988, under then-Mayor Harold Washington. “Harold Washington made public health a priority,” she says. “His theory was that public health is for people, not profit. His vision was that we know where the high-risk areas are, and we have limited resources. So why put resources where the low risks are?”

Norman oversaw professional services, including the school health program, dental program, and health education. In addition to deploying 1,200 public health nurses to vulnerable neighborhoods, she recruited health educators from high-risk communities.

Some of today’s problems are similar to those in the ’80s, at the height of the AIDS crisis, when public health professionals worked with community-based organizations to provide contact screening, referrals, and follow-up.

In the wake of Covid-19, Chicago needs to increase the number of public health nurses, health educators, and community outreach coordinators in Chicago’s high-risk communities, Norman says. “This is more critical now than ever before,” she says. “It worked in the past, and it can certainly help save lives and prevent further harm in the future.”

Collaborative efforts

Two miles west of the Loop, the Illinois Medical District (IMD) — the state’s largest healthcare and technology innovation district — exists in one of Chicago’s more vulnerable areas. Encompassing multiple city blocks, the IMD hosts private and public healthcare facilities, including John H. Stroger, Jr. Hospital of Cook County, Jesse Brown VA Medical Center, Rush University Medical Center, and UI Health.

The IMD, tasked with fostering economic growth, is in a unique position to bring together private and public efforts to improve neighborhood health in the city. But it’s not an easy road, due in part to broken trust between communities and health systems.

“You have many who are wary and distrustful of government, healthcare, and media,” says Suzet McKinney, DrPH, CEO of the IMD.

In the Black community, that distrust stems from incidents when systems meant to protect people instead took advantage of them. While many examples of this exist, two with direct impact on people still alive today include the Tuskegee Study and the story of the Lacks family.

In the former, the U.S. Public Health Service ran syphilis experiments on Black men from 1932 to 1972, withholding treatment until many of them died from the disease or its complications.

The latter involved Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman diagnosed with cervical cancer in 1951. Without her family’s knowledge, researchers took her rapidly reproducing cells and have used them ever since in landmark medical developments, such as the polio vaccine and in vitro fertilization. While companies that retail the cells have profited into the billions, the Lacks family has fought to make ends meet.

“I hope hospitals and healthcare systems will recognize not just that these disparities exist but pay attention to the reasons. Let’s face it, it’s Covid-19 today, but a year from now it’ll be something else,” says McKinney, who sees private sector jobs and investment as one solution.

“Often with government and nonprofit entities, funding can be unstable. It depends on grant dollars and other funds. Those challenges don’t exist as often in the private sector,” McKinney says.

During negotiations to attract healthcare and tech businesses to the area, McKinney talks about inequities. Two years ago, when Superior Ambulance was considering locating to the IMD, McKinney asked if the company would offer local employment opportunities. Superior committed to training 100 community residents as emergency medical technicians and medical billing specialists within the first year.

“That’s 100 not just individual lives, but complete families whose trajectory has completely changed,” McKinney says.

Ansell is out to change lives, too. With a community health focus, he led an effort to bring together local hospitals to brainstorm ways to address the West Side’s inequities. Collectively, they formed West Side United.

The six health systems involved in West Side United — AMITA Health, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Cook County Health, Rush University Medical Center, Sinai Health System, and UI Health — have valuable insight.

By collaborating, they aim to halve the life expectancy gap between the West Side and downtown by 2030, hire 3,500 West Side residents, and invest $7.5 million across 20 Chicago communities by 2021.

“For the first time in the history of our city, you have health systems that were traditionally competitors coming together to share hiring and procurement data to invest in West Side communities,” says West Side United Executive Director Ayesha Jaco, who grew up in East Garfield Park. “People want jobs, access to care, safe neighborhoods, and meaningful things for young people to do, including equitable access to education.”

Before Covid-19, West Side United’s health strategies focused on hypertension, maternal-child health, and standardizing care among hospitals and federally qualified health centers.

To respond to the pandemic, the organization joined forces with Mayor Lori Lightfoot to form the Racial Equity Rapid Response Team. The group aims to mitigate Covid-19 illnesses and deaths in Black and brown communities through senior wellness checks, food pantry funding, small business emergency microgrants, and personal protective equipment delivery.

Jaco says the team exemplifies one way the city has acknowledged a historical disinvestment from vulnerable communities. However, she adds, “We are working to ensure the strong alignment of federal, state, and local resources, because we have a model that works.”

Systemic solutions

Nonprofit and community groups are often important drivers of change in Chicago. By bringing together stakeholders, they play a key role in addressing health disparities across the city.

At Heartland Alliance, health policy expert Dan Rabbitt works with elected officials on policy development. “It starts with a recognition that racial inequity is a fundamental challenge to our nation,” he says. “In an ideal future, we’d all agree on that.”

Collaborative approaches are necessary, he says, but there are no simple solutions. “If we can see it as a systemic problem that needs to be solved by systemic policies, that would be a big step,” he says. “These inequities are generations in the making, so they’re going to need time to be undone.”

For nearly 30 years, Heartland Alliance has addressed the city’s health inequities by working directly with individuals experiencing homelessness. As with health issues, homelessness hits Black residents harder. Of the 77,000 people experiencing homelessness in Chicago, about 47,000 are Black.

“The Black community has strong and well-meaning families, but they’re overburdened,” says Stellon at Heartland Alliance. “White families just have a little extra, a little more wealth. There are probably lots of people in more privileged communities who would otherwise be homeless, but they have those people who can make room. Who literally have a spare room.”

It’s daunting work to address these disparities and effectively support communities, but solutions exist. Some of the more famous examples came about during the Great Depression, when Americans faced massive unemployment. Then-President Franklin Roosevelt created the Works Progress Administration to provide public infrastructure jobs. The Social Security Act guaranteed pensions and unemployment insurance.

“We have in the past had systemic solutions, like Social Security or Medicare, and they’re not as radical as they sound,” Stellon says. “It can work, keep people off the streets, out of harm’s way, out of emergency departments. We have big problems, but we’ve also had big solutions, and we have to not be afraid of those.”

These broad-reaching public investments continued through the ’60s and ’70s in various forms, such as subsidized housing and increased federal investment in public education.

Locally in the ’60s, Chicago Public Schools (CPS) began a practical nursing program for high school students — giving students hands-on nursing experience and a degree, which led to job prospects upon graduation.

Darko enrolled in the program in 2001, splitting her last two years of high school between Whitney Young High School and Crane High School, where she trained to become a licensed practical nurse.

The program was a thoughtful public response to creating well-paying jobs and training healthcare providers in underserved communities. However, CPS cut the program in 2014.

“We terribly need more nurses, so [cutting the program] is just going to compound all of the issues healthcare is currently facing,” Darko says.

More broadly since the ’80s, federal and local governments have gradually disinvested from public programs, such as mental health, housing, and education — all areas that have a direct impact on health.

In an oft-cited example, in 1981 then-President Ronald Reagan cut federal mental health spending by 30%, resulting in increased homelessness and incarceration.

Three decades later in Chicago, another sweeping disinvestment happened when then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel closed 50 schools in primarily Black and brown neighborhoods — the largest mass school closure in modern U.S. history.

But our communities need more investment, not less, to close the health gap.

Putting people first

As Cook County commissioner for the 2nd District, Dennis Deer, PhD, wants to help close that gap by spurring economic development and expanding access to affordable healthcare.

His district encompasses multiple West Side and South Side neighborhoods as well as the Loop. “This is a community where we have not had the best fortune, and we want to turn that around. It may not take a day, a week, or a year, but we’re going to keep at it,” Deer says.

There’s a chance for local government to get more involved. “I have this vision of a hospital without walls, of reaching out into the community. They don’t come to us. We go to them,” he says.

Deer wants to raise awareness about complex issues of racism and health. In July 2019, the Cook County Board of Commissioners passed Deer’s resolution that declared racism and racial inequalities a public health crisis in Cook County.

“The minute you start talking about something as a crisis, people’s antennae go up. They pay attention,” Deer says. “People over politics. It’s always people.”

Darko, as she embarks on her medical residency, is ready to serve the people. “We know there are social aspects that affect our health,” she says. “Everyone says, ‘Eat right. You need to work out.’ But no one gives people the tools to properly do those things. I think it’s important to not just tell people what to do.”

In addition to public education, there also needs to be better access to health insurance. Add the 40 million Americans who lost their jobs due to Covid-19 and the 30 million already uninsured in the U.S., and you’ll see the problems with a health insurance system that’s largely tied to employers.

“If we’re going to have capitalism as our main way of doing business, which has certain advantages, it has to be heavily regulated to give people rights like universal basic income, healthcare, and housing,” Ansell says. It’s time to use this moment, when the spotlight is focused on health disparities from Covid-19, to systemically address health inequities.

“This is a moment in time we could possibly get it better, maybe even get it right,” Ansell says.

It’s time to fix the hole in the road.