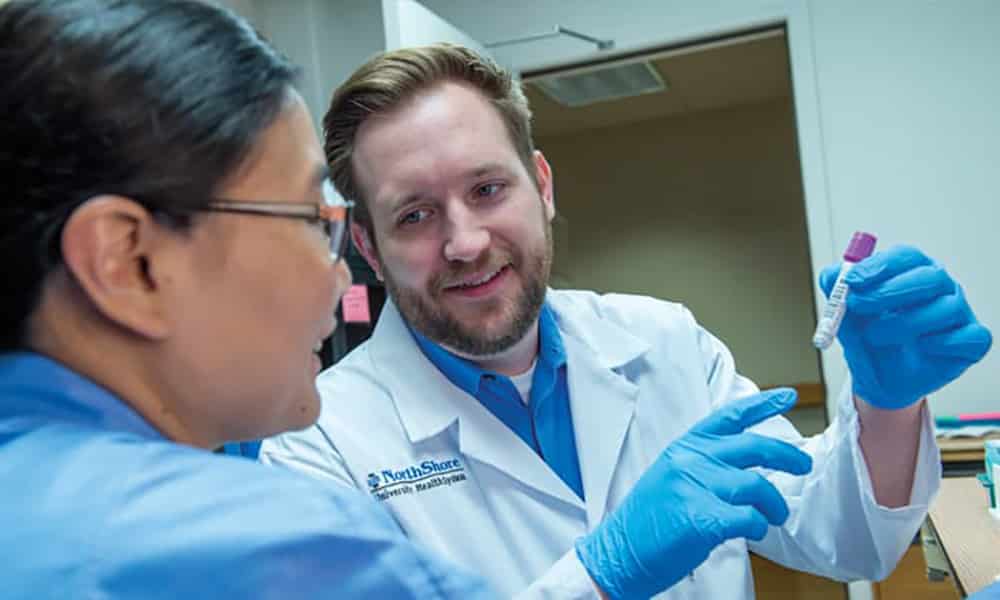

Photo above: Mark Dunnenberger, PharmD. Courtesy of Jonathan Hillenbrand, Media Production and Photography, NorthShore University HealthSystem

Genetic testing drives decision-making in personalized medicine

The future of medicine is personalized. Personalized medicine uses information about a patient’s genetics, lifestyle and environment to manage his or her healthcare. From genetic testing to determining which drugs work best, this approach to healthcare is revolutionizing diagnosis, prevention and treatment. And the feds support it with President Obama’s $215 million Precision Medicine Initiative. Of that money, $50 million is being allocated to local biomedical researchers.

The Genomic Health Initiative, part of the Center for Personalized Medicine at NorthShore University HealthSystem, is a major research endeavor where clinicians, researchers and members of the Chicagoland community are hoping to shape the future of personalized medicine.

The local initiative seeks to understand the correlation between genomics and disease by collecting a large number of DNA samples with the intent to also contribute data to the federal initiative.

“It’s an exciting time because this is really, to me, personalized medicine at its finest,” says Michael Caplan, MD, chief scientific officer at NorthShore University HealthSystem. “For patients [who] didn’t know anything was wrong, we can identify things that they can do that will improve their health just by analyzing their genomic background.”

A simple cheek swab or blood draw can be used to calculate a person’s risk for a variety of health issues, including cancers, cardiovascular diseases, blood clots and genetic disorders. Personalized medicine allows physicians to use that information to tailor a patient’s screening and proactively identify early stages of these conditions.

While personalized medicine is a rapidly evolving emphasis for the medical community, genetic testing is not a new science. The first widely used genetic tests date back to the 1960s when newborns were tested for phenylketonuria, an inherited metabolic condition that can cause intellectual disability and other serious health problems.

More recently, celebrities like Angelina Jolie Pitt brought awareness to genetic testing for the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes associated with breast cancer and ovarian cancer. Jolie famously underwent a preventative double mastectomy and, later, had her ovaries and fallopian tubes removed after discovering a BRCA1 gene mutation that put her at increased risk of breast cancer and ovarian cancer. (See Defending Yourself Against Ovarian Cancer, the Silent Killer, page 32.)

“All of us are at risk for cancer; the question is what is that risk; is it higher or lower than the average, and what cancers are you more at risk for?” Caplan says.

Caplan points out that personalized medicine cannot predict what a patient will develop, but the results, along with counseling from clinicians and specialists, will help a patient understand his or her own unique risks.

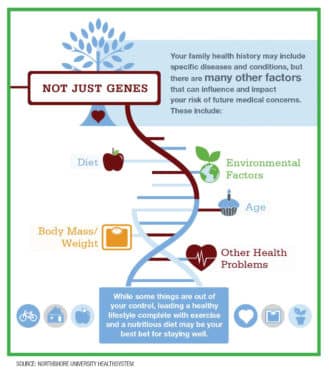

Morris Fiddler, PhD, president and managing member of Insight Medical Genetics, notes that one significant change in the field of genetics over the last several decades is the acknowledgment that both nature and nurture play a role in our health.

“We have come to appreciate that we are not only influenced by our environment and not only driven by our genes, but that there are, in many ways, interactions between the two that we have yet to really understand,” Fiddler says.

An individual’s family health history may include specific diseases and conditions, but additional factors including diet, age, body mass, other health problems and environmental factors all influence a person’s risk of future medical concerns.

Certified genetic counselor Lauren Bryl of Insight Medical Genetics believes that the biggest genetic breakthrough in recent history was the advancement of next-generation sequencing (NGS). This discovery reduced the time to sequence an entire human genome from more than a decade down to a few days, at a cost of around $1,000.

“It really changed the types of tests that are feasible to offer patients in all realms of genetics,” she says.

One aspect of personalized medicine is a rapidly emerging field known as pharmacogenomics, which is the study of how an individual’s genetic makeup influences his or her response to different medications.

Henry “Mark” Dunnenberger, PharmD, director of pharmacogenomics at NorthShore University HealthSystem, says that his patients are “not so comfortable knowing their disease risk or the risk of something happening in the future, but they are comfortable with having a drug therapy tailored to their genetics.”

In today’s pharmaceutical-laden world, with sometimes a dozen or more drugs available for a given disorder, pharmacogenomics helps identify the medications most likely to work and least likely to cause side effects for a patient’s existing medical problems, including psychiatric disorders, cardiovascular conditions, depression, epilepsy, gastrointestinal disorders, infectious diseases and pain management.

“If we know ahead of time that the first couple of efforts can be sidestepped, because we know you’re not going to metabolize a drug in a way that’s going to be effective, we’ve just saved time as well as periods of unhappiness,” Fiddler says.

Retired OB/GYN Tony Cirrincione participated in a NorthShore clinical pilot studying 15 genes involved in metabolizing and transporting drugs. He learned that he inherited two variant copies of the mu-opioid receptor, which meant he had no normal receptors to respond to opioids for pain.

Prior to his genetic testing, Cirrincione suffered from kidney stones and was given the opioid Dilaudid intravenously. He told the emergency room doctor “this stuff is making me dizzy, but the pain’s the same.” The doctor, believing the dosage was not strong enough, gave Cirrincione more of the drug. It did not help.

Cirrincione’s next experience with kidney stones was less painful, because it came after his genetic test results. He was given the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug Ketorlac, which does not use the mu-opioid receptor, and his pain was lessened.

Cirrincione refers to his genetic testing as “a curiosity that led to dramatic results.”

Current challenges and the future of personalized medicine

Privacy of a patient’s genomic data in his or her health record and the expense of genomic testing might prevent some patients from participating in personalized medicine.

Advancements are still needed for the full interpretation of the massive amounts of data collected, especially as the desire to augment clinical care through personalized research continues to grow.

“Our ability to do analytical lab work is outpacing our understanding of what the data means and how to use it,” Dunnenberger says.

But on the positive side, Dunnenberger notes, “Genetic tests can be done once, even on a 5-year-old, and that result can have value throughout the patient’s lifetime.”

The ultimate goal of personalized medicine is allowing those results to be used to favorably guide the patient’s care at the exact moment it is needed.