As measles cases in Chicago remain low and vaccinations increase, here’s what to know about the latest outbreak

While her sons played one Sunday evening in early March, Yulia* tried to locate a suitcase. The family was staying at the Pilsen migrant shelter, but they had plans to move north, to reunite with Yulia’s husband, who had left for a job. Then the news came.

Two representatives — one from the city and one from Chicago Public Schools — told Yulia that because of measles cases within the shelter, she and her children would have to quarantine for the next 21 days. The family’s plans: delayed.

The city’s first measles case was not from a shelter resident. However, residents were particularly vulnerable due to lower vaccination rates and communal living. Officials needed time to sort through everyone’s vaccination status.

The City of Chicago reported a week later that all of the roughly 1,800 people within the Pilsen shelter had been vaccinated. As of March 20, 15 cases total have been identified in the city. In each case, the person is recovering, but fears about measles within and beyond the shelter remain.

A forgotten fear

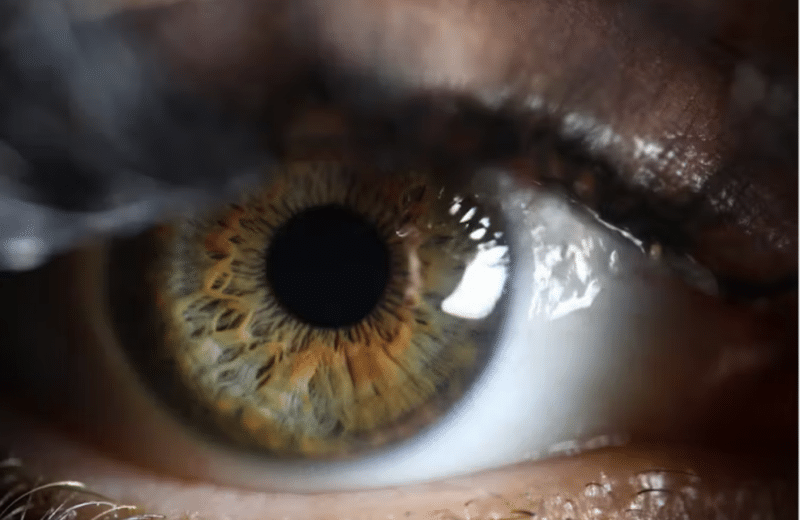

Measles is a highly contagious respiratory disease. Early symptoms include a high fever, cough, runny nose, and rash. Complications can escalate to ear infections, diarrhea and dehydration, blindness, brain swelling, brain damage, and severe breathing problems.

“People forget how bad it was prior to vaccinations,” says Jonathan Pinsky, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Endeavor Health.

Before the measles vaccine became available in 1963, the disease caused 2.6 million deaths worldwide every year. “If you are exposed to measles and not vaccinated, you have a 90% chance of getting measles. Anyone born before 1957 is assumed to have been infected naturally with measles,” Pinsky says. “The data is that 1 to 3 of every 1,000 children who get measles will die. Prior to the vaccinations, when you have an entire population infected, that’s a lot of children being infected and dying.”

For comparison, 128,000 people died of measles in 2021. The vaccine — measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) — comes in two recommended doses. Children receive the first dose around age 1 and the second before age 6. Two doses are 98% effective against measles, while one dose is 93% effective.

“In schools it is a requirement to be adequately vaccinated for measles. You can see now why it’s an important requirement,” Pinsky says.

If you’re unsure whether you’ve been vaccinated, start by checking with your primary care physician to see if they have records. While MMR vaccination began in the 1960s, the two-dose protocol didn’t start until 1989. People concerned about their vaccination status can undergo a blood test to check their measles antibody level.

Measles vaccines are essential for personal and public health

World Health Organization officials in January issued an alert that measles outbreaks internationally are on the rise due to declining vaccination rates. Also in January, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned of a “growing global threat” from measles, with nearly two dozen cases reported recently throughout the country, primarily in unvaccinated children and teens.

The U.S. isn’t immune to these global trends. Vaccination rates have declined in the U.S. in recent years, in large part because the MMR vaccine has been falsely linked to autism. Seventy years after the vaccine’s release, some parents are hesitant or flat out refuse to vaccinate their children. Pinsky says those conspiracies simply aren’t true, and put many at risk of real danger.

“There’s no evidence that MMR or any other vaccine causes autism,” he says. “It’s a myth, and it was debunked. It was perpetuated by a small study that was found to have many errors. They removed that study from the journal, but it was very hard to undo. Other large epidemiological studies showed no link to autism.”

In an email to families, Chicago Public Schools Chief Executive Officer Pedro Martinez wrote this past Friday, “The vast majority of Chicago residents — more than 90% — are protected from measles by the measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine. It is one of the highest vaccination rates in the country.” He added that the MMR vaccine is “a safe, highly effective vaccine that is given in childhood and is a requirement for students enrolled in CPS schools.”

World Health Organization officials in January issued an alert that measles outbreaks internationally are on the rise due to declining vaccination rates. Also in January, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned of a “growing global threat” from measles, with nearly two dozen cases reported recently throughout the country, primarily in unvaccinated children and teens.

After the first week of quarantine at the Pilsen shelter, Yulia worries that the cold weather will sprout more sickness. She says some people are following the city’s guidelines for quarantine. Many, though, are not. And with everyone now vaccinated, Yulia says people seem more worried about the city potentially closing the shelters than they are about measles.

*Name changed for privacy