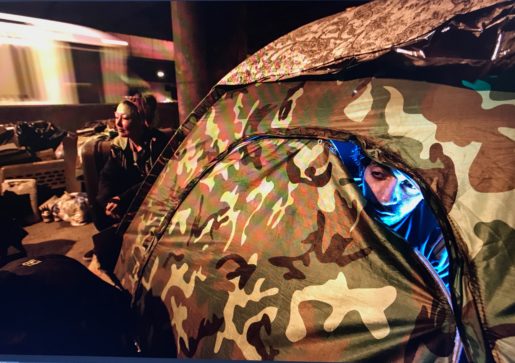

Near Chicago’s $100 million Riverwalk and luxury high-rise apartments, unsheltered homeless people “sleep rough” on the side of the road. One resident, Drew, lives in an approximately 200-square-foot camp where he shares cigarettes and a portable bathroom with five other people. They typically don’t wear masks around each other.

Despite these health risks, he isn’t afraid of getting Covid-19. He thinks the virus’s severity can’t compare to the shaking, aching, vomit-inducing experience of each of his attempts to cut back from opiates, which can permanently damage areas of people’s brains that affect their ability to make decisions and regulate self-destructive behaviors such as drug use.

“I have bigger things to worry about than Covid. I have to eat. My son has to eat. I honestly wouldn’t care,” he says. “A lot of us are at the end of our ropes.”

Drew spends his days panhandling to support himself and his 11-month-old son, who lives with his mom. Like many other homeless people, he says he hasn’t been able to make half of what he made before the pandemic emptied the streets. The rare passerby sometimes apologizes and says that they’ve lost their job or taken on medical debts, so they don’t have any money to donate.

Even if he were worried about Covid-19, Drew says he doesn’t know any unsheltered person who has gotten the virus or experienced symptoms. Several other unsheltered Chicagoans also say that, in their experience, people sleeping outside seemed to have largely avoided Covid-19.

Yet while outreach groups are managing the risks of Covid-19 in Chicago’s homeless shelters through careful testing and intervention, comparatively little is known about how the virus has impacted unsheltered people like Drew.

This lack of data is becoming increasingly dangerous as a high incidence of Covid-19 coincides with below-freezing temperatures, and outdoor sleepers eschew the safety of social distancing to sleep inside CTA trains.

Unknown effect on those who are unsheltered

Unpublished testing data from the Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH) supports the idea that unsheltered homeless people in Chicago have avoided the large outbreaks that hit Chicago’s shelters, says Isaac Ghinai, MBBS, a CDC epidemic intelligence service officer who works at the CDPH.

But medical professionals from The Night Ministry, a nonprofit group that works with Chicago’s homeless, and Rush University Medical Center warn that Covid-19 rates and outcomes in unsheltered homeless people are harder to track because they face more barriers in accessing the medical system than those in shelters.

In fact, more is unknown than known about unsheltered homeless people’s experiences with the virus in Chicago and beyond. While dozens of studies have focused on Covid-19’s impact on homeless shelters nationwide, there’s little public data on how the virus has impacted the unsheltered homeless population, despite this group’s potential vulnerability.

A 2019 study by the California Policy Lab found that unsheltered homeless people were four times more likely to self-report a physical health condition than sheltered homeless people and more than five times as likely to report substance abuse — two factors that place them at risk of more severe Covid-19, according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

Healthcare providers such as Stephan Koruba, The Night Ministry’s senior nurse practitioner, are worried that the estimated 1,260 Chicagoans who “sleep rough” like Drew may finally face a Covid-19 outbreak now that the CTA has become the city’s largest unofficial shelter. That is, if the rough sleepers haven’t gone through an unnoticed outbreak already.

“If this gets into the rough-sleeping population on the CTA, hundreds and hundreds of folks will be at risk instantly,” Koruba says. “And the problem is, we don’t have the data to inform the development of new programs, what resources are going to be needed, and just basically how to approach this.”

But they’re working to collect that data. Twice a week, The Night Ministry provides medical care, food, case management, supplies, and clothing at the Forest Park Blue Line and 95th Street Red Line “L” stops during late evening and early morning hours. The two-year pilot project with funding from CDPH was designed to respond to the challenges that this segment of Chicago’s homeless population faces. While delivering services, The Night Ministry is also noting how to better address needs related to Covid-19 and other health, safety, and housing issues.

Risks for rough sleepers

While Covid-19’s effects are better known in the approximately 4,030 people who live in Chicago’s shelters, people who are unsheltered face different challenges. And this group is harder for healthcare providers to reach.

The Chicago Homelessness Health Response Group for Equity (CHHRGE), a collective of medical providers and shelter operators founded in March, has been working to address Covid-19’s impact on people experiencing homelessness in Chicago. It has been coordinating the city’s efforts to test entire shelters after one positive case is detected. This has reduced the Covid-19 positivity rate in Chicago’s shelters from 21% in April to less than 2% in June, according to CDPH data.

Ghinai led a study published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases in October that identified risk factors for Covid’s spread in homeless shelters, which can help inform prevention efforts in those spaces. The study found that more people sharing common bedrooms and bathrooms increased the likelihood of infection.

However, the research on rates and risk factors in homeless shelters is not applicable to the one in five homeless people who sleep rough or thousands more who temporarily double up with friends or family.

The rough sleepers live in a more unpredictable environment, says Angela Moss, PhD, assistant dean of faculty practice for Rush University’s College of Nursing and medical director of the nonprofit A Safe Haven’s isolation space for homeless people with Covid-19 symptoms.

They’re open to a unique set of Covid-19 risks, Moss says. “It depends on where they’re sleeping, who’s around them. There’s a lot of factors that, as a person experiencing homelessness, you don’t have control over.”

Stacey, for example, relies on donated dollar bills and coins that she collects in highly trafficked areas, increasing her possible Covid-19 exposure. She lives in the same camp as Drew on Lower Wacker Drive, where social distancing is impossible. Though the city gave her camp a handwashing station, the water now smells like rotten eggs, she says.

“It needs to be bleached out. If you use that to wash your hands, you have to use hand sanitizer afterward or use bottled water,” Stacey says. “But I’m afraid to take it apart, and they come and say we’ve vandalized property if I can’t get it put back together.”

Kelly, 40, is sleeping on the Blue Line “L” train this winter, where anyone could sit next to her and expose her to Covid-19. She says that she wears a mask sometimes, mostly so that people won’t be afraid to drop money in her cup. Yet despite the risks she faces, she has remained safe from the virus.

She says she doesn’t know of many homeless people who have gotten Covid-19. “I was tested twice. I wonder if maybe it’s our immune system, because we’re outside all the time,” she says. “It’s funny because there’s all these people that are scared of us, when it should be the other way around. We should be scared of them. They could get it from work. I usually just sit here with my sign.”

Koruba, however, is very worried about the many risks that Kelly, Stacey, Drew, and other unsheltered homeless people might face during this wave, especially because they don’t usually see healthcare professionals.

Providers across the city are trying to address this gap as they plan Covid-19 mitigation efforts. Members of CHHRGE have organized social workers and medical teams to refer people sleeping on trains to resources for housing or medical care, Koruba says.

An emergency release from the beginning of the pandemic allows the Night Ministry’s mobile team of nurse practitioners, case managers, and outreach professionals to call providers to authorize prescriptions and to charge those consultations to Medicare or Medicaid. This makes it easier to provide treatments to people on the street, Koruba says.

But while the city has provided rapid Covid-19 tests to shelter residents for months, rapid tests only became available to unsheltered train sleepers in late-January, Koruba says. CDPH and Lawndale Christian Health Center collaborated to provide a limited number of rapid BinaxNOW tests — the same test used in shelters — for real-time testing of symptomatic patients on the train and in the street. The rapid tests, though not in widespread use currently for train sleepers, enable street medicine teams to quickly give results and direct people to the proper resources.

So for now, healthcare providers will plan with incomplete information and hope that winter passes without an outbreak.

Drew will keep waking up to the sound of 7 a.m. traffic, panhandling near Michigan Avenue, and hoping that spring will bring an end to lockdowns, a renewed flow of generous pedestrians, and a flattening of the pandemic.

Top photo: Stephan Koruba (left), a nurse practitioner at The Night Ministry, tests an unsheltered person for Covid-19. He estimates he has administered over 20 tests to Chicago’s homeless, all negative. Photo by Lloyd DeGrane

Caroline Catherman is a health and science reporter whose work has been published in Science Magazine, Chicago Health Online, Chicago Reader, and Orlando Sentinel. She graduated with an MSJ from the Medill School of Journalism in June 2021.