But advancements give new hope for children with sickle cell disease

Martha Strong’s son Marrion came out screaming.

“He was actually having his very first pain crisis as he was being pushed out of me,” Strong says.

What she didn’t know then, but would learn very soon, was that Marrion had sickle cell disease, a genetic blood disorder that can cause acute pain crises and serious bacterial infections in the blood, lung, brain or bone.

In sickle cell disease, the hemoglobin in red blood cells, usually round and flexible, is curved like a sickle (hence the disease’s name). The odd shape causes red blood cells to clump and stick together, blocking blood flow and causing anemia, extreme pain and susceptibility to severe, often life-threatening infections. Life expectancies range from just 42 to 48 years.

Strong knew that she had one sickle cell gene and one normal gene, meaning that she did not have sickle cell disease but could pass the gene on. If both parents have the gene, there is a 25 percent chance that their child will have the disease.

“I knew all my life that I had the sickle cell trait, but I never knew exactly what the disease could do,” Strong says. “I pretty much found out right then, spot on, head first. Confused and very scared was my first reaction.”

An early diagnosis

Sickle cell disease affects approx- imately 100,000 Americans. And overwhelmingly, those children are black. The rate of the disease among newborns is 73.1 per 1,000 births for African-Americans, compared to 6.9 per 1,000 births for Hispanic Americans and 3 per 1,000 births for white Americans.

Martha Strong went on to have four more children — two of whom, Makayla, 4, and Monye, 1, also have sickle cell disease. Marrion is now 8 years old.

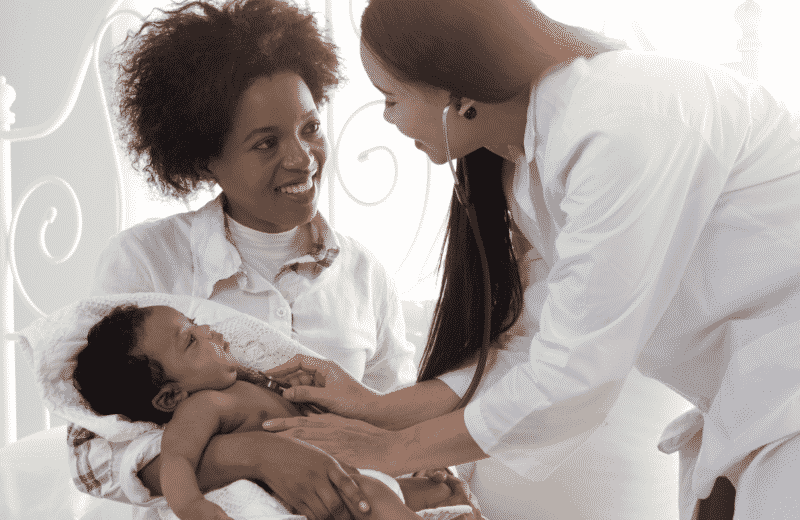

“For sickle cell disease, early diagnosis is vital,” says Radhika Peddinti, MD, clinical director of the Sickle Cell Disease Program at UChicago Medicine. Diagnoses are made through newborn screenings that look for hemoglobin abnormalities, a routine practice in Illinois since 1989.

“By the time the babies [with sickle cell disease] are six to eight weeks of age, we put them on preventive antibiotics,” says Peddinti, who is the Strong children’s physician at La Rabida Children’s Hospital.

The early introduction of penicillin is one of the biggest advancements in caring for children with sickle cell disease, preventing the infections that used to be a major cause of death in the first five years of life. Now, Peddinti says, those infections are exceedingly rare.

“The earlier you put comprehensive care into place, the better it is,” Peddinti says. If the newborn screening comes up positive for sickle cell disease, “we go over the diagnosis and what it entails, put them on prophylactic penicillin, start their immunizations and then get them plugged into healthcare as soon as we can.”

A disease with a stigma

Pediatric care for sickle cell disease, at least in areas like Chicago with high-quality health systems, is generally quite comprehensive. At La Rabida, physicians follow a “medical home model” — a patient-centered care model focused on both preventive treatments and continuous, specialized care.

Children are followed closely, and pain, infections and general illnesses are treated as quickly as possible with the best resources available.

At 18, however, children with sickle cell disease lose this comprehensive support system. Adults with sickle cell frequently end up in emergency rooms for treatment for infections or raging pain. And with restrictions on opioid prescriptions, it’s harder for them to get pain relief.

“It’s a very stigmatized disease on the adult side,” Peddinti says. Adult sickle cell patients experiencing regular and excruciating pain crises are viewed by many physicians as “mostly drug-seeking patients,” she adds, “so they’re wary to talk about their diagnosis.”

A future without sickle cell disease?

The stigma and lack of coordinated care for adults with sickle cell disease highlight the need for early, curative treatments. And there have been advancements. In 2011, an adult sickle cell patient at UI Health became the first person in the Midwest to receive a stem cell transplant as part of her treat- ment. Six months later, she was cured.

“Stem cell transplantation replaces a patient’s stem cells, which are making red blood cells with the sickle mutation, with stem cells from a relative who can make non-sickle-cell red blood cells,” says Santosh Saraf, MD, assistant professor of clinical medicine and director of translational research at UI Health’s Sickle Cell Center.

“The sickled red blood cells are no longer produced, leading to … improvements in red blood cell breakdown, resolution of the anemia and reduced red blood cell blockage of blood vessels,” he says.

Since that first patient, UI Health has cured 40 patients through bone marrow stem cell transplantation, Saraf says. Twenty-six were cured using completely matched stem cells from a relative, and 14 were cured using half-matched stem cells from a relative.

While stem cell transplantation, also referred to as bone marrow trans- plantation, is incredibly promising, the lack of appropriate and available donors means it’s not quite a universal cure yet. When donors are matched siblings, stem cell transplantation is over 95 percent effective in pediatric patients. However, only 18 percent of patients have a matched sibling donor.

There are new medications — in particular, a drug called Hydroxyurea — that drastically cut down on sickle cell-related complications. Exciting things are happening with gene therapy too, with researchers working on isolating, and ideally correcting, the molecular defect that causes the disease in the first place.

“Scientifically, we have a cure for this disease,” Peddinti says. “The problem is how many resources are we pumping into this and how accessible is this to everybody?”

For Strong and her children, at least, having the support of a medical team makes all the difference in how they’re able to cope with the complications and illnesses that so often arise as a result of the disease.

“As a mother with three children withsickle cell disease, it’s very overwhelming,” Strong says. “Emotionally you get frustrated, exhausted and you don’t know what the next step is. You can go off the deep end so fast.”

Her advice for other parents facing a sickle cell diagnosis with their child? Learn as much as you can and get your support system set up as early as possible. “Keep your faith,” she says. “It helps a lot.”