By talking about their differences, children can self-advocate and build confidence

Tommy O’Leary appreciates a good joke. Occasionally, when a curious kid asks about his prosthetic leg, he says a shark attacked him. To Tommy, the made-up version is more exciting than the real story.

MaryKay O’Leary, Tommy’s mom, feels differently. She reminds him that he can start with the shark story for laughs, but then she encourages him to tell the truth.

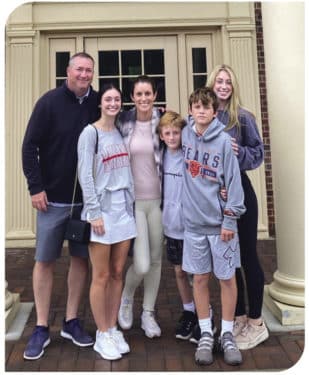

By now, Tommy, 11, is an expert at explaining the condition that led to his prosthetic leg. He was born with fibular hemimelia, a rare birth defect that caused him to be born without a fibula (one of the two bones in the lower leg) and deformed bones in his ankle. MaryKay and her husband Jim consulted specialists and did research, ultimately deciding that amputation and a prosthetic leg would give Tommy the best quality of life. At 10 months old, he had a below-the-knee amputation at Shriners Children’s Chicago. He got his first prosthetic leg a month later.

The youngest of four, Tommy understands and easily explains his difference, because he and his family have always talked openly about it. Still, as a speech pathologist who works with children who have special needs, MaryKay understands why some parents might choose to hide their child’s disability from others or even from the child. They may fear that people will label them or that the child will use the disability as a crutch.

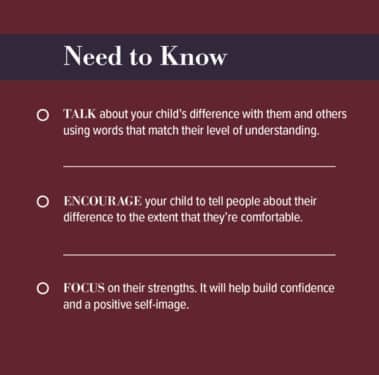

“It’s a natural feeling to want to protect your child,” MaryKay says. “But sometimes in secrecy or trying to hide it, you’re telling your child that something’s wrong with them. Nothing’s wrong with them. There’s just a difference.”

For MaryKay, embracing disabilities and being open and honest about them, is a game changer. “If they know how they feel and are able to attach meaning to it, they can better advocate for themselves and educate others,” she says. “By educating others, they decrease stigma and negativity.”

Knowledge empowers

If parents choose not to tell a child about their disability, the child is going to eventually realize their difference and likely come up with their own reason for it. The reason they create might be harsher on their self-confidence than the diagnosis, cautions Jennifer Carlson, PhD, pediatric psychologist at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

For example, imagine a child who doesn’t know they have a communication disorder, such as autism. They may struggle to make friends, and mistakenly think of themselves as stupid or uncool. If other kids classify them in that way, they’ll lack the knowledge to explain themselves.

On top of that, if a child doesn’t know why they’re struggling, they might have trouble finding resources to help compensate for those challenges, Carlson says. Yet resources will help them participate in the world to whatever extent they want. With dyslexia, for example, Carlson says, “You can listen to an audiobook and still participate in a reading club. There are lots of things you can do to bypass it, to make that disability not disabling.”

Self-advocacy and acceptance

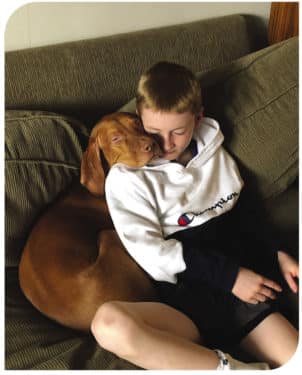

For Tommy, a prosthetic leg enables him to do gymnastics; play volleyball, basketball, and football; and ride a bike. Knowing why he has the prosthetic lets him talk to others about it confidently.

At the pool, while Tommy takes off his prosthetic leg before hopping into the water, MaryKay often overhears parents telling their kids not to stare. She’ll ask the children if they want to see his leg. “I know it looks different from yours,” she says. Then she’ll explain the difference, showing them where their fibula is and involving Tommy in the conversation.

MaryKay follows Tommy’s lead. “Tommy is open about showing his leg,” she says. “He’ll take it off if someone wants to see it. The kids are so interested, and once they hear it, they’re satisfied. After you put it out there, they see Tommy for Tommy. He’s not the kid with the prosthetic leg.”

“Childhood and adolescence is about developing your own self-identity,” says Kathy Zebracki, PhD, chief of psychology at Shriners Children’s Chicago. “You want your child to be confident and proud of who they are and the young adult they are becoming. Focus on what they’re able to do, on their strengths. Help them develop their own identity, one that is not defined by their disability.”

Have the conversation

If you’re not ready to talk with your child, Carlson suggests parents meet with a therapist and together decide how best to approach teaching their child. Or read books specific to the child’s condition. For children with autism, Carlson often recommends The Little Book of Autism FAQs: How to talk with your child about their diagnosis and other conversations by psychologist Davida Hartman to learn how to discuss it.

Participation fosters a sense of belonging and empathy, and helps children relate to others. “I encourage children to join adaptive sports and recreational activities that are of interest. Summer camps for children with similar challenges can be a wonderful experience and help build their confidence,” Zebracki says.

At the beginning of each school year, Tommy’s teacher would read The Adventures of Thomas…Thomas gets a new leg! Tommy’s grandmother Maureen McCluskey wrote the book to tell his story. But by fifth grade, Tommy told his mom the teacher didn’t need to read to the class anymore. “Everyone knows me,” he said.

And they know him as the funny, independent, and confident child he is. Mission accomplished.

Above photo: Tommy O’Leary (jumping in) and his brother Seamus swim while visiting their great grandparents during Christmas break

Originally published in the Fall 2022/Winter 2023 print issue.

Melanie Kalmar is a journalist specializing in business, healthcare, human interest, and real estate. When not writing, she enjoys spending time with family.