Families and researchers press for new treatments

Tim Paust loved life. At work, he was an aircraft maintenance manager for Motorola, but it was his family and friends who made up his heart.

“Tim was the love of my life and just a great guy,” says his widow, Deb Paust, 58, who lives in Grayslake. The couple met in high school and built a life together that included three children, now all grown: Brad, Sammie, and Jake. Tim was an active, involved parent who coached football for 14 years and lacrosse for six.

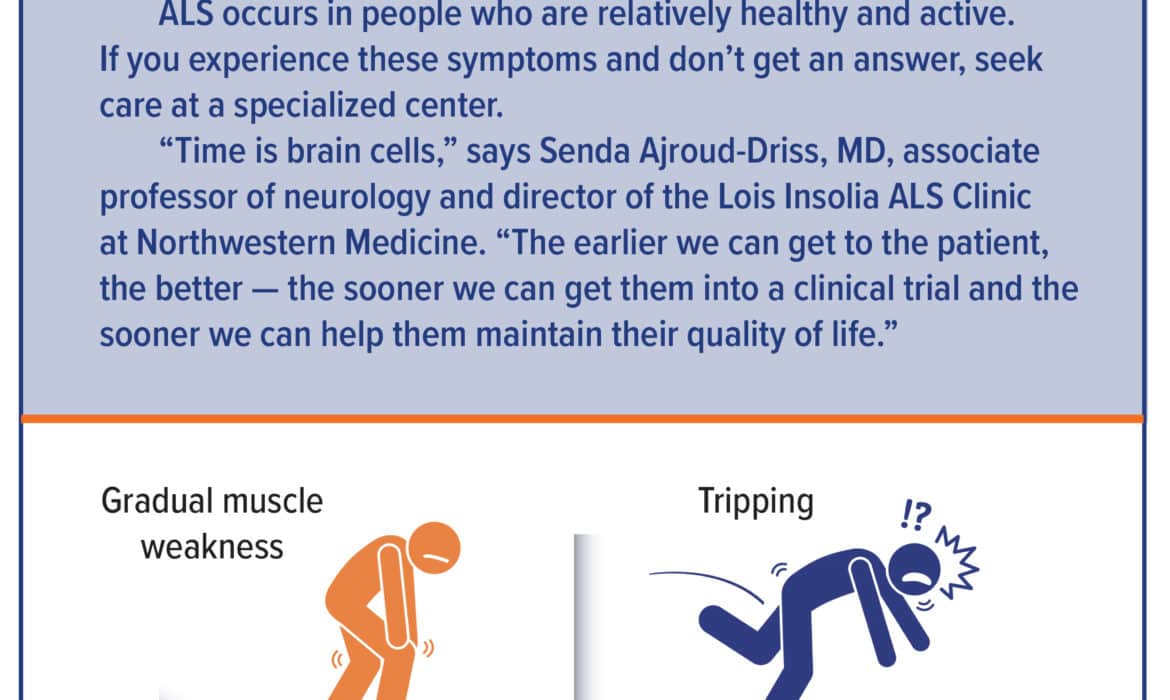

In 2011, Tim started to experience some unusual symptoms, including cramping in his hands and legs. Deb, a physical therapist assistant at the time, suspected that he might have amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), but she kept her fears to herself.

“He was sleeping a lot and not doing as much, which was out of character,” she says. At a work Christmas party, he admitted that he couldn’t dance because he was afraid he might fall. A few months later, at age 48, he was diagnosed with ALS.

From the time of his initial diagnosis in March 2012, he lived two years and two months. Most of his day-to-day care fell to Deb. Their children also helped care for their dad as his condition worsened.

The family spent Tim’s last days together at his favorite place, their cabin in Wisconsin. “It was sad and beautiful at the same time. Tim was in and out of consciousness. We wanted him to feel the love around him, so we played games and slept in the same room together, never leaving him alone.”

ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a neurodegenerative disease that affects the nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord. The progressive loss of motor neurons means a person gradually loses the ability to control muscular movements, including the ability to eat and breathe, athough their intellectual capabilities usually remain intact.

There is no cure yet, but researchers are studying the effectiveness of new drugs in clinical trials, and families like the Pausts are advocating for more funding for this kind of research.

Deteriorating function

ALS is a particularly grim diagnosis. Steve McMichael, a former Chicago Bears player, shared his ALS diagnosis with the public earlier in 2021, disclosing that the disease was affecting his motor skills.

“ALS is a condition that affects cells in the brain and spinal cord, called motor neurons,” says Madhu Soni, MD, associate professor of neurological sciences and director of the ALS clinic at Rush University Medical Center. “These motor neurons can be considered the source of information, nourishment, and energy to the muscle.”

As ALS progresses, the motor neurons deteriorate. This, in turn, impacts the muscles’ nourishment, causing atrophy and weakness. “The muscles affected are those that are under voluntary control and allow us, for example, to walk, talk, eat, and breathe,” Soni says.

About 10% of cases are familial, but the majority are sporadic, with no known cause. ALS is more common in people over the age of 50 than in younger people, and it appears slightly more often in men than women, though that predominance disappears after menopause, suggesting that female hormones may play a protective role.

While ALS is a terminal condition, Ajroud-Driss says the disease progresses differently in different patients. “When I meet with patients [after they are diagnosed], usually there is no clear indication of how the disease will progress,” she says.

While the disease itself cannot be cured, the field has changed tremendously in terms of being able to manage ALS symptoms, improving quality of life, and slowing progression. “There are FDA-approved medications for ALS to slow the decline in function and to treat specific symptoms,” Soni says.

The future of treatment

Specialists are hopeful about ongoing research. There is no cure in sight, but scientists are identifying associated genes and studying new drugs for treatment.

The ALS Association’s 2014 Ice Bucket Challenge raised more than $115 million, much of which has been used for research. Since then, researchers have identified 11 new genes associated with ALS, each of which may be a therapeutic target. New drugs that slow disease progression, including AMXOO35 from Amlyx Pharmaceuticals, are closer to approval, and clinical trial efforts are working to decrease the time of ALS drug trials by 50%.

“There are an unprecedented number of ongoing research trials for ALS,” Soni says. “Those of us who care for people with ALS are eagerly awaiting the results of these studies with the hope that additional medications will become available in the near future to change the trajectory of the disease.”

Deb Paust became more involved with ALS advocacy and volunteer work after Tim died, hoping to make a difference in the lives of others affected by ALS. She advocates for ALS-related legislation to secure funding and change public policy to accelerate treatments and cures. She also works directly with people who have recently been diagnosed.

“I do it in Tim’s honor,” she says. “Advocating helps me through my grief.” She feels empowered using what she has learned to aid other families with ALS. “I just have to roll up my sleeves, dive in, and do what I can to help others.”