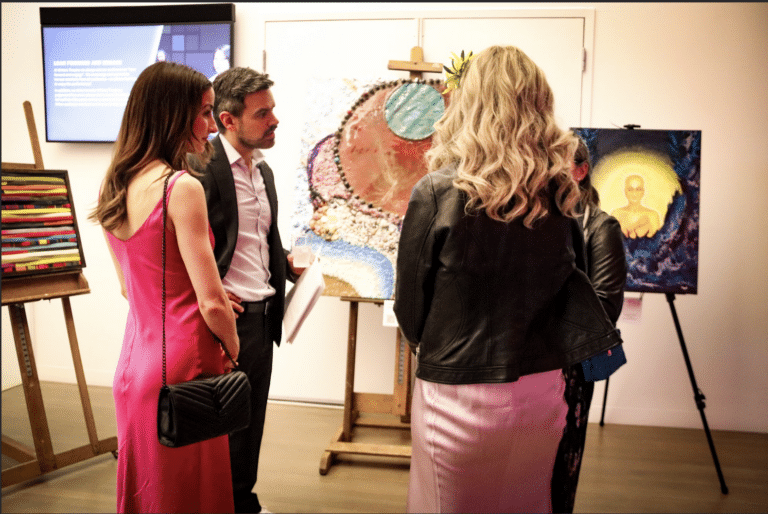

Pictured above: Theater production of “Cats” by Artful Impact

Rachel Gossan, a board-certified behavior analyst at North Shore Pediatric Therapy, has had some remarkable patients. She remembers an 8-year-old who could do lightning-fast calculations of large numbers in his head and come up with the correct answer. She recalls a teen who would ask people their date of birth and then accurately tell them the day of the week they were born.

“Some people with autism have exceptional abilities in five categories: calendar calculation, mathematics, art, music and mechanical skills,” she says. “Research now says that one in 10 people with autism has a special skill, but there is a range in the degree of these abilities.”

Each person with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) has a unique set of symptoms that can range from mild to severe. They may be intellectually challenged or gifted; they may have mild or intense repetitive behaviors such as flapping their hands or rocking their bodies; they may be insensitive or very sensitive to pain, touch, smell, sound or taste; they may have various degrees of difficulty communicating with others, expressing their feelings or understanding the feelings of others; and they may have special skills or abilities.

With April as National Autism Awareness Month, the nonprofit Autism Society is focusing not only on promoting inclusion and providing opportunities for people with autism, but also on appreciating people with ASD for their unique talents and gifts.

Skill building

In her professional practice, Gossan uses Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), a scientifically validated approach that has been utilized since the 1960s to help children with autism increase skills and abilities and decrease negative behaviors.

“In ABA, we often break down skills, such as social skills and language, into smaller parts, and we shape these behaviors until the child has learned the entire skill,” Gossan says. To decrease negative behaviors, such as biting or hand flapping, Gossan first determines the reason why the child is acting that way—perhaps they are trying to escape an unfavorable task or trying to get an adult’s attention—then she works to extinguish the behavior, replacing it with more appropriate behaviors that serve the same purpose.

It’s important for parents to seek early help so that they can reap the most benefits out of ABA therapy. “Early diagnosis and intervention are really important, and the earlier the better,” she says. “We have some at our clinic as young as 2, and we see them make amazing growth.”

On the spectrum

Heather Hutchison has seen many young people on the spectrum with special abilities and skills. She was a faculty member at The School of Performing Arts in Naperville, when her son Christopher was diagnosed with autism. Early on, she discovered that he found ways to express himself in music, dance and role-playing—skills that were untapped elsewhere.

Christopher was the impetus for Hutchison to create Spectrum, the theater arts program of Artful Impact, the not-for-profit arm of the School of Performing Arts. Spectrum offers year-round arts programming for young people with ASD and other developmental disabilities. Students rehearse and perform a cabaret show and a musical each year. “We have some kids with autism who have absolutely perfect pitch. We find pretty much across the board that they have a unique sense of rhythm and can find the rhythm in different types of songs,” Hutchison says.

Hutchison also finds that the students are passionate about doing research. “As soon as they know the theme of the cabaret or the particular play or musical we’re going to do,” she notes, “nine times out of 10, the kids will come in with the songs memorized, and they’ll know about the major characters and random facts about the composer or a famous actor who was in the show.”

Symptoms that may be pronounced in the students’ daily lives tend to disappear on stage. Kids who normally have difficulty expressing emotions may succeed at portraying deep feelings during a performance. “It doesn’t take a lot for them to understand that this is pretend and to separate themselves from their characters,” Hutchison explains.

When she launched Spectrum eight years ago, Hutchison was warned that she couldn’t teach people with autism to feel empathy for others. But that has not been the case. “It’s sometimes challenging during the rehearsal process,” she says, “but when it comes down to the wire at show time—when you would think it would be high pressure and high sensory—100 percent of them are on the edge of their seats backstage rooting for each other, supporting each other, clapping for each other. They have a beautiful sense of how hard it has been for everybody to get from point A to point B.”

The importance of acceptance

Hutchison’s son Christopher is now 20. He has graduated from high school and is close to finishing a transitional program that will enable him to find employment and live independently. While Hutchison says she is incredibly grateful for the organizations that raise funds for autism research, she stresses the importance of increasing acceptance.

“We need to be very aware that we have autistic people that need jobs, that need friends, that need opportunities, that need people to treat them like regular human beings,” she says. “I work with these kids week in and week out, and I’m telling you they can learn and be accountable. For quite a lot of them, as long as they feel comfortable and safe, they don’t need hand holding.”

Adds Gossan, “Today we talk about a person with autism—not an autistic person—because the person falls somewhere on the spectrum. We’re looking at the individual, not the label.” Recognizing those with autism not for their differences, but for their myriad of exceptional abilities, helps them live successful, fulfilling lives.

Nancy Maes, who studied and worked in France for 10 years, writes about health, cultural events, food and the healing power of the arts.