A shift in approach delivers a dose of hope

Pain has always played a role in Kristen Willard’s life. She was born with a congenital defect in her back — a fusing of two vertebrae that made her more susceptible to back injuries. She first hurt her back at 16 and has had ongoing issues with back pain since then.

“The pain has ebbed and flowed my whole life,” says Willard, 44, who lives in Downers Grove. “It got so I could almost feel it coming on — like, ‘Oh, my back’s going to go out.’ I would do something as simple as put a spoon in the dishwasher, and I’d be out for days.”

Willard has tried everything from seeing doctors and chiropractors to taking medication and doing exercises. But after she turned 40, the pain got even worse.

“The pain never left, and it was totally debilitating to me,” says Willard, who eventually had to quit her job because of the pain. “It affected my kids and our whole house. … I didn’t really complain about it, but my family could see it and feel it.”

One in five adults in the U.S. is living with chronic pain, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In the past, opioids were one of the front lines of defense. But the overprescribing of opioids has led to widespread misuse, addiction, overdose and death.

Because of the opioid epidemic, physicians are looking at ways to treat chronic pain without narcotic pain medications. And attitudes and treatments are changing, to the ultimate benefit of the 50 million Americans who face this kind of unrelenting discomfort.

Understanding pain

Say you sprain your ankle — a relatively uncomplicated injury. Your body’s nervous system triggers pain sensations to let you know that you may be hurt and to help you avoid further injury. As your ankle heals, your pain recedes. That’s tissue-related pain, and it often resolves.

Other pain, called central sensitization pain, can occur when your body’s nervous system keeps sending pain signals to your brain — even in the absence of tissue injury. This is the kind of pain that’s linked with conditions like fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome.

Whether your pain is tissue-related or complex, chronic pain is defined as pain that occurs on most days within the past six months, according to the CDC.

Chronic pain is more prevalent than people realize because most people don’t talk about it, says Shana Margolis, MD, an attending physician at Shirley Ryan AbilityLab’s Pain Management Center.

- The most common types of chronic pain include:

- Headaches/migraines.

- Low back pain.

- Osteoarthritis.

- Neurogenic pain, or pain caused by nerve damage.

- Central sensitization pain.

While it’s not clear whether more people are experiencing chronic pain than in the past, there’s certainly more attention being paid to it, says ATI physical therapist Tom Denninger, DPT.

“From a boots-on-the-ground perspective, we are treating more patients with more complex pain,” Denninger says. “We have patients with pain like lower back and neck pain, and then we have a whole other group of patients with complex pain, which includes patients with fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, chronic fatigue syndrome and other persistent diffuse pain. And what we’ve learned over the last 10, 20 or 30 years is that for these patients, who have a lot of healthcare utilization, pain isn’t necessarily a tissue issue … as much as the oversensitivity of the central nervous system.”

Evaluating pain and its impact

Evaluating a patient’s pain is critical to being able to make an accurate diagnosis of its source, says Wellington K. Hsu, MD, the Clifford C. Raisbeck distinguished professor of orthopaedic surgery at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine.

“We want to figure out the cause of the pain. It could be soft-tissue-related, to structural, to a fracture, to arthritis,” says Hsu, who treats people with back pain. “The treatment we recommend really depends on the diagnosis. Some conditions do well with surgery, while others are treated with more conservative care.”

While chronic pain can strike anyone, you’re more likely to experience it as you grow older, says Henry Finn, MD, medical director of the Chicago Center for Orthopedics at Weiss Memorial Hospital and professor of orthopedic surgery at University of Chicago.

People tend to want a procedure or a pill or surgery. They want something done to them instead of doing something [themselves]. But we want to put the patient in control and teach them how to better manage their pain.”

“Deterioration of key joints, such as the hip and knee, is a primary source of debilitating pain in many of my patients,” Finn says. “Excessive buildup of scar tissue, hidden infections and allergies to metal can all cause pain, as well as osteoarthritis caused by repetitive movement, obesity, genetics, bleeding disorders and wear and tear with age. Accurately diagnosing the cause of pain and implementing the right solution is tricky but gratifying.”

Part of the challenge of evaluating pain is that while other vital signs — like heart rate and blood pressure — are objective and relatively easy to measure, pain is subjective. Everyone has a different pain threshold, so doctors consider a variety of factors when analyzing pain:

- How long has the person had the pain?

- What does the pain feel like?

- Where is the pain located? Is it always in the same place?

- How much does it impact functionality or ability to do the things the person normally does?

- Is the pain getting better or worse? What kinds of things help it or make it worse?

Less reliance on opioids

In the past, pain was likely to be treated with drugs, with a goal of reducing as much pain as possible.

“There was a push to manage acute and chronic pain, and one of the main things was medications. At the time, it was thought that opioids were safe, so it became a common way to treat pain,” Margolis says. “Now we have an opioid epidemic, and there’s a big push to minimize opioid abuse … and to use non-opioid meds and alternative treatments to better manage pain.”

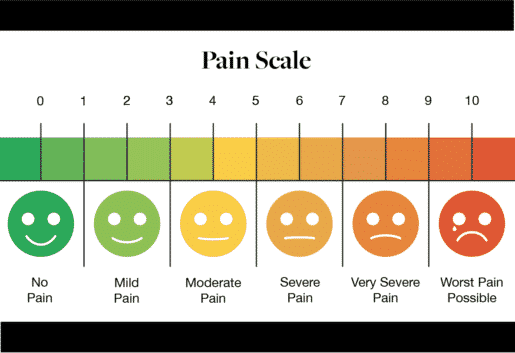

Another change in approach is to instill more reasonable expectations about pain management. “The goal isn’t necessarily for pain to completely go away,” Margolis says. “But if you can go from a 7 to a 4 [on the pain scale], that may be a good response.” In fact, going from having pain to no pain at all may mean you’re overtreating it, she adds.

The goal of pain management today is to put patients in control of their pain and to minimize opioid use when possible. Doctors are turning to different classes of medications to assist with pain control, including steroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), muscle relaxants and anti-depressants.

“We have learned that putting patients on chronic opioid medications after surgery is really putting patients at risk,” Hsu says. “We know the opioid epidemic is a real problem and that physicians have fueled this issue.”

Doctors are also slower to recommend surgery if pain can be managed with less invasive options. If surgery is necessary, minimally invasive surgery and other cutting-edge techniques help lower the pain associated with it. And doctors are finding that changing post-surgery recommendations helps manage post-op pain as well

“We realize that after surgery, early activity is good,” Hsu says. Getting patients up and moving and controlling pain with light narcotics or NSAIDs can help hasten the healing process and lead to fewer complications like pneumonia, blood clots and infections.

Taking control of pain

Part of treating chronic pain today is about changing the perception of what pain means and how to handle it.

“We’ve been taught that if there’s a problem, there’s a pill for it,” Denninger says. “We’re taught to freak out about pain and that if you have pain, something is wrong and something should be done about it.” This knee-jerk reaction may drive patients to overmedicate themselves. It also overlooks the fact that different kinds of pain require different approaches.

For patients with central sensitization, one of the most important things is a reconceptualization of what they are experiencing. “There’s this very prevalent idea of ‘I’m broken — I’m falling apart,’” Denninger says. “We need to help people conceptualize that this is a sensitivity issue, not a tissue to be fixed. It’s like a car alarm going off with a gust of wind.” In other words, pain may be a nuisance or uncomfortable, but it’s not necessarily an indicator that something physical is wrong or needs to be “fixed.”

In fact, people with chronic pain related to central sensitization issues usually find no relief from opioids. One of the most effective methods of pain management is simply getting people moving and giving them a sense of control — one they may have lost over years of dealing with chronic pain.

Lifestyle modifications that help improve overall health — things like eating a nutritious diet and getting quality sleep — can also help with pain management. The idea is to educate people about what they can do to deal with pain, instead of simply hoping that something will magically eliminate their discomfort.

“People tend to want a procedure or a pill or surgery. They want something done to them instead of doing something [themselves],” Margolis says. “But we want to put the patient in control and teach them how to better manage their pain and how to pace themselves.”

“The push is on multidisciplinary treatments and getting patients functioning well,” she says. In addition to traditional treatments like medication, surgery and physical therapy, physicians are using electrical stimulation, nerve blocks, acupuncture, psychotherapy, biofeedback and other complementary and alternative approaches to help patients manage pain.

Willard has found some success of late seeing an orthopedic physical therapist and chiropractor several times a week and doing physical therapy exercises at home. It’s made a difference in her pain and what she’s able to do.

While she’s still dealing with pain, she says it’s more manageable. “Sometimes it’s five steps forward and three steps back … and the pain is definitely still with me every day, but I can do things,” says Willard, who is now working as a substitute teacher. “And sometimes I even forget it’s there. I’m in a much better place.”

Ellen Ryan is an award-winning writer/editor specializing in profiles, Q&As, and case studies; consumer health; education and career change, business; and grammatical near-perfectionism. (Nobody’s perfect.)