ER physicians battle on the frontlines of gun violence response

Fact checked by Shannon Sparks

Nearly 80% of the 2,880 shooting victims in Chicago in 2023 survived, thanks largely to city hospitals’ emergency rooms. Here, we go in-depth with the emergency medicine physicians who stand at the frontlines of the gun violence epidemic, confronting the harrowing aftermath of firearm injuries. Along with their clinical teams, they navigate a landscape where swift, decisive action can mean the difference between life and death.

These medical professionals are not just healers but also first responders to a public health crisis, facing the stark realities of trauma daily. Their experiences in treating gunshot victims reveal a profound commitment to patient care, resilience in the face of repeated tragedy, and a comprehensive understanding of gun violence as a symptom of larger societal issues. Their stories highlight the urgent need for comprehensive solutions and support systems to address gun violence’s pervasive impact on individuals and communities.

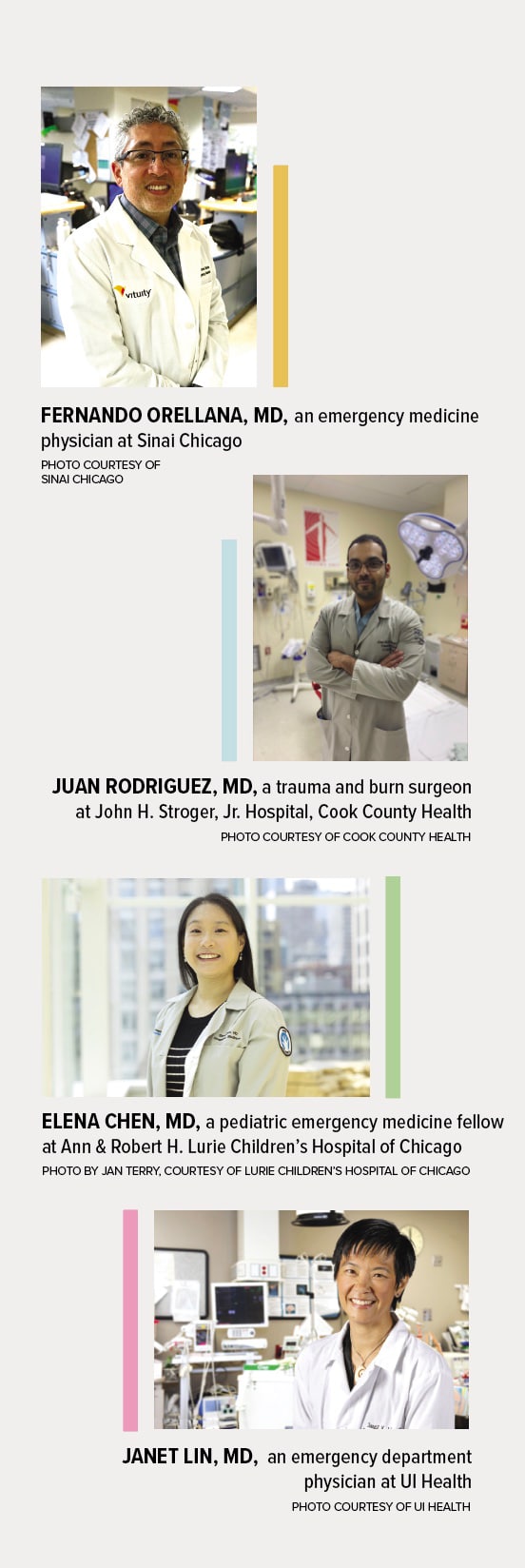

Fernando Orellana, MD, an emergency medicine physician at Sinai Chicago

Juan Rodriguez, MD, a trauma and burn surgeon at John H. Stroger, Jr. Hospital, Cook County Health

Elena Chen, MD, a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago

Janet Lin, MD, an emergency department physician at UI Health

What motivated you to specialize in emergency medicine?

Juan Rodriguez: I wanted to be able to make a difference by serving patients on what is likely their worst day. In a trauma unit, you are able to make an impact on so many people across the entire spectrum of humanity. I am originally from Chicago. While I did my residency in a rural trauma center, I knew I wanted to serve patients in my hometown.

Elena Chen: I wanted to care for all children regardless of circumstances. As the healthcare safety net, the emergency department provides me with an opportunity to care for every child and family that comes through our doors.

How often do you typically treat gunshot victims?

Fernando Orellana: I’ve seen approximately 50,000 patients in my career so far. Gun violence victims — over 5,000 patients. This includes victims and the families.

Rodriguez: Last year we cared for 771 patients with gun injuries at Stroger Hospital’s trauma unit.

Chen: Over the course of five years of training in general pediatrics and pediatric emergency medicine, I’ve cared for about 50 children who were victims of firearm injuries.

Is this what you expected when you went into emergency medicine?

Orellana: When I entered emergency medicine, I was well aware of the trauma and gun violence victims that I would take care of. I just never imagined the amount. Also, the actual day-to-day care of these victims brings the reality front and center.

Chen: As a pediatric resident, I did not expect to care for so many children with firearm injuries. Based on the cases of children I have cared for, and knowledge of the impact gun violence has on children’s health, I am resigned to the fact I will likely continue to care for children who are victims of gun violence, both to treat acute injuries and long-lasting physical and mental health consequences of those injuries.

Janet Lin: In some sense yes. However, the pervasiveness of gun violence in our society — no. And when I see young, innocent, bystander victims of gun violence, it is heartbreaking.

What’s a particularly impactful case involving a gun violence victim that has stuck with you?

Orellana: A father committed gun violence on his two children to get back at his ex-wife. The children arrived with gunshot wounds to the head. They did not survive. Everyone in our department did everything that we could, yet we felt like failures. There was not a dry eye in the house. Staff members were haunted by this experience for many months.

Chen: I took care of a child who was caught in the crossfire of a shooting. A few months later, they returned to the emergency department. The mother thanked me for caring for her child at the time of the injury. When I asked her how they were doing, she told me it was hard, but she was grateful for her child’s life. That stayed with me. In an instant, the bullet caused her child to develop a significant and lifelong disability. It changed the life trajectory not only for the child but for the entire family.

Lin: One of the first patients I cared for was a self-inflicted gunshot wound. He had attempted to commit suicide by shooting himself in the face underneath his jaw. Because of the force of the recoil of the rifle, it forced his head further back, so he survived. However, his face was partially shot off. Nothing vital was injured, but he required extensive plastic surgery to repair his face. I had a chance to see him several weeks later in clinic after he had been discharged. He was happy that he had survived. But it left me reflecting upon the ease with which he [obtained] a gun.

How has your experience with treating gunshot victims changed your perspective on gun violence over time?

Rodriguez: I’ve realized that as much as we hear about gun violence, many people don’t fully understand it. We can’t be complacent with seeing the statistics or reading the news and moving on. Gun violence is a symptom of much larger societal drivers and inequities that need to be addressed holistically. I also think that many people have preconceived notions about individuals who are injured with a firearm. What they don’t realize is that many patients injured by firearms are unintentional targets or had a relatively routine interaction that unpredictably escalated to violence. We need to do more to raise awareness about the complex effects of gun violence and how it impacts not only a patient and their family, but our whole community.

Chen: We know there are a few preventable scenarios that can instantaneously and permanently change a child’s life. In my mind, these are drowning, motor vehicle accidents, and other accidents such as accidental ingestions and household accidents. I now have to include random gun violence in this list. For most of these other scenarios, we have evidence-based research on how to decrease these events and laws or policies in place to prevent events (i.e., seat belts, speed limits, car seats). But for gun violence, there is only limited available research on how to prevent these events, and numerous available policy opportunities to prevent child firearm injuries remain to be enacted.

In what ways do you think the healthcare system is currently well-equipped or ill-equipped to handle gun violence cases?

Orellana: I believe that in the United States, we have the best medical technology and the best-trained staff, so in this way we are very well equipped to care for gun violence victims. We are not doing as well on the mental health front — mental health for the victims and the staff [who] treat these victims.

Rodriguez: Approximately 25% of the traumatic injuries we see in our unit are penetrating traumas caused by gun or knife wounds. Most other hospitals across the country see 12% to 14% penetrating trauma. Because we see such a wide range of injuries, we were selected to be a medical training site for the U.S. Navy. Navy surgeons, nurses, and corpsmen rotate through our hospital to get training on treating penetrating trauma and other injuries before being deployed. What has become increasingly challenging is the proliferation of high-capacity magazines, automatic firearm modifications, and bullets that contain explosive components. These are truly weapons of war, causing massive and immediate destruction. It wouldn’t matter if I got the patient on an operating table in seconds; the damage can be catastrophic.

What needs to change in healthcare or medicine to better respond to gunshot victims?

Rodriguez: A public health approach must be applied to gun violence in the U.S. if we, as a society, hope to reduce gun-related morbidity and mortality. The U.S. Surgeon General’s recent declaration of gun violence as a public health crisis is an important first step in this endeavor.

Chen: I think resources should be allocated to better support patients and their families after the initial event, including resources to support physical health, mental health, and social support. These resources help with recovery and can prevent reinjury, because unfortunately a number of gunshot victims go on to have additional gunshot injuries.

Lin: In the emergency department we are dealing with the downstream — meaning, treating the gunshot victim. More needs to be done to address the upstream: the root causes of why there are gunshot victims. That is multifactorial and needs to be addressed at multiple levels.

What keeps you going?

Orellana: Teaching, passing the torch properly to the next generation of providers. Unfortunately, we will still need great resilient and caring providers to care for these types of victims.

Rodriguez: I fall back on my Christian faith for a sense of purpose and life of service; my family for the support they have provided me over the years; and my colleagues for working alongside me, as I would not be able to do my job without them.

Chen: The families I care for and my amazing colleagues in the emergency department.

Lin: Hope that each of us, together, can make a difference.

Above photo by Jim Vondruska

Originally published in the Fall 2024/Winter 2025 print issue.

Catherine Gianaro, a freelance writer and editor based in Chicago, has written about healthcare and higher education for more than three decades. With 90-plus awards in communications, she is well-versed in storytelling.