Cartoons use their visual power to promote healing and acceptance

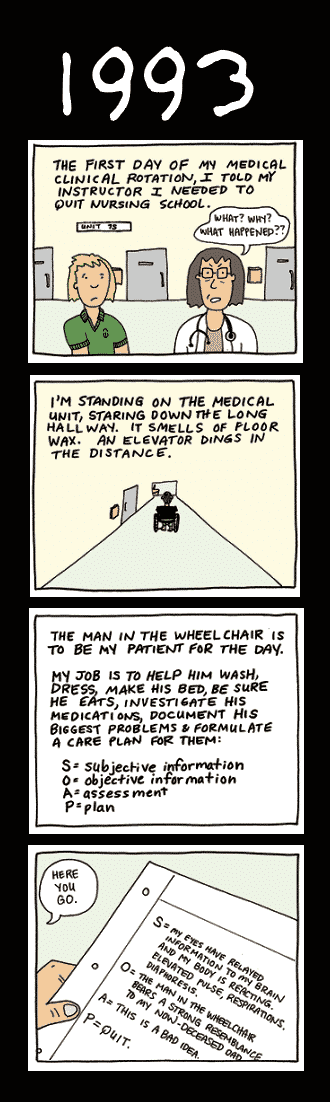

M.K. Czerwiec, RN, was a brand-new nurse, still in nursing school, as excited and full of anxiety as any of her peers. She was worried about her care plans and forgetting her stethoscope. But she had something else to contend with: grief. Her father had died unexpectedly, right before she started her clinical training in a Chicago hospital.

Her first floor assignment involved caring for a patient who looked very much like her father. The assignment triggered her grief, and she barely got through her shift. Shaken by this overwhelming experience, Czerwiec wanted to quit nursing before she had even started, but a kind nursing instructor intervened.

After graduation, Czerwiec got a job caring for patients on a dedicated HIV/AIDS unit at another hospital. She desperately needed a way to cope with the stress of the unit. So she started drawing a series of pictures of the upsetting situation. Then, she added words. The visual combination of words and pictures, in comic form, had a powerful healing quality.

“I found the sequential nature of the panels very helpful,” she recalls. “They moved me from the despair of the moment to a hopeful position.”

Artists, like Czerwiec, along with activists and therapists, are tapping into a trend of using graphic novels and cartoons to support people with mental health issues, using humor and satire to help them cope.

Cartoons in clinic

Clinicians are using comics to better reach patients, too. At the University of Illinois at Chicago, researchers use cartoons to connect with teens and prevent depression. The program, called CATCH-IT, is geared toward teens ages 13 to 18 who show early signs of depression. Catching the symptoms through comics can prevent a full-blown depressive episode.

“We had to use the edutainment model to actually catch their attention,” says Benjamin Van Voorhees, MD, MPH, a UI Health pediatrician who co-developed the program with Tracy R.G. Gladstone, PhD, of the Wellesley Centers for Women. “We keep evolving the modalities and adding innovation because technology is so much more sophisticated now.”

Teens in the program look at cartoon panels on a computer screen and choose different scenarios. For example, in one scene, a boy is rejected by a girl. The system then coaches the user about positive coping skills, such as tools for dealing with stress and techniques to stop negative thoughts. Participants learn to track their moods and identify their triggers.

Parents also get involved, with a series of modules that educate them about mental health and encourage them to empathize with their child’s struggles. The cartoon-based program reduces the risk of severe depression by 80%, Van Voorhees says.

Humor and empathy

Visual power

Czerwiec — who runs the graphicmedicine.org website along with three colleagues — says artists are following a long tradition of using comics to be subversive and push for change. Czerwiec has taught graphic medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and the University of Illinois Chicago College of Medicine, among others.

Comics deliver healthcare information in a new way. “I think cartoons are very accessible. If you can make someone laugh, they will be open to hearing what you have to say,” says Tamsin Walker, a British artist known for her single-panel cartoons.

Walker created a graphic novel called Not My Shame to process past sexual trauma. Through the MadZines project, she researches zines as a way to challenge the way we think about mental health.

The movement is growing. Seattle artist Ellen Forney has told her mental health story in her graphic novels, Marbles and Rock Steady. She aptly depicts the highs and lows of bipolar disorder using the visual metaphor of a carousel horse going up and down with the moods. Another artist, Gemma Correll, who lives in California, has 880,000 Instagram followers for her single-panel comics chronicling her anxiety and depression.

Visual images connect in ways that words do not. For instance, Czerwiec uses comics to help medical students at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine develop more empathy for their patients. First, she has them draw a patient encounter the way they remember it. Then, they imagine what the patient was thinking three hours before and after the office visit.

While drawing these panels, the students are able to step into their patients’ shoes, a habit that could go a long way toward improving mental health and healthcare.

Graphic medicine will certainly help increase acceptance of mental health issues, but Van Voorhees doubts it can totally erase the negative perceptions many people have about mental illness and seeking treatment.

Yet, Van Voorhees believes there’s hope for the future — and for graphic medicine — because teens are more accepting of mental health concerns.

“The truth is, there are so many people with anxiety and depression, and there are more treatments than ever before,” he says. “My hope is these interventions will do a lot to normalize that stigma.”

When a person struggles with mental health issues, they can feel like they are alone and nobody understands, Walker says. “People think you just need to pull your socks up. I think for discrimination to end, we need to change how we value people overall.”

And she’s hoping that comics play a valuable role in doing just that.

Originally published in the Fall/Winter 2021 print issue.

Melissa Ramsdell is a nurse and professional freelancer specializing in health writing. She has a BSN and a master’s in journalism.