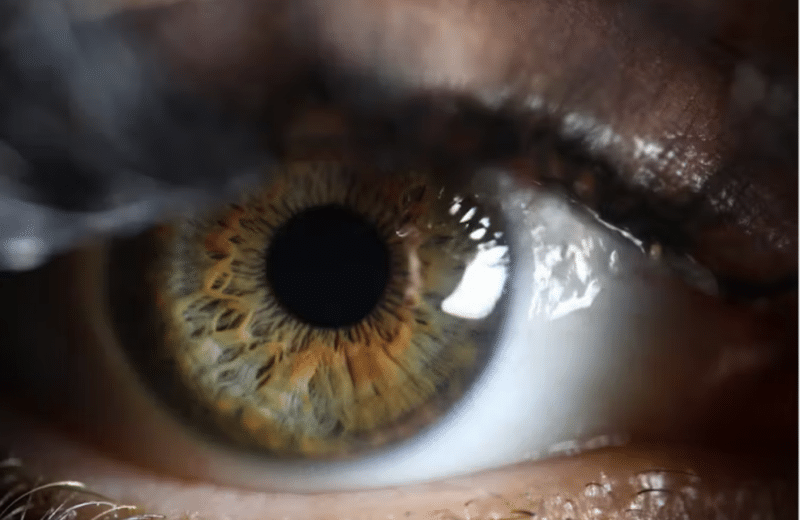

For seven years, I went to different optometrists and ophthalmologists with a nagging, intermittent complaint. Sometimes once a week, sometimes once a month, my vision became cloudy in one eye, and I felt as though I were peering through a foggy window. It made work difficult, and when driving at night, I’d see halos around headlights and street lamps.

I’d always come back from the appointments with a clean bill of health, and then as my vision blurred once again, I’d turn to the Internet—brain tumors and diabetes running through my thoughts.

Finally, last spring, I met with yet another optometrist, and he immediately knew what I was describing. “I think I can make it happen right here in the office,” he said. He then proceeded to press a Q-tip to my lower lid, and, lo and behold, the familiar cloud set in. “Dry eye disease,” he said. To help clear my vision, he suggested eye drops, warm compresses and wearing my glasses more, rather than contacts.

Dry eye disease, which sounds quite serious—disease!—is really more of a nuisance that occurs when the eye produces too few tears, or tears of low quality. The result can be a sandy, gritty feeling in the eye, stinging, redness and blurred vision. It’s something eye care professionals are seeing more and more.

Dry eye is the most common corneal- and ocular-surface disease, affecting 100 million people worldwide, according to Mark Rosenblatt, MD, professor and head of the Department of Ophthalmology & Visual Sciences at University of Illinois at Chicago.

While it rarely leads to more serious problems, dry eye is a hindrance that can be concerning, Rosenblatt says. “We’re taking it more seriously. It used it be, ‘Oh, you have dry eye. It might not be a big deal.’ But the consequences of dry eye, in terms of morbidity and in terms of lost productivity, are becoming more apparent,” he says.

Once found primarily in patients older than 65, more younger people are presenting with dry eye. Michelle Andreoli, MD, an ophthalmologist at Wheaton Eye Clinic, says she’s seeing it surface in people who spend the day staring at the computer, blinking less frequently, in offices with dry air. She says dry eye also occurs more in people who wear contacts, perimenopausal and postmenopausal women, thyroid patients, patients with rheumatoid arthritis and people taking chronic antihistamines, such as allergy medication, which can have dehydrating effects.

Andreoli says the blurry vision will often set in during the late afternoon, after a person has been at the computer all day, and make it difficult to work. “If your day stops being productive at 2:00 or 3:00 in the afternoon because your corneas are dried out, that’s really significant in terms of productivity. It really has a big impact,” she says.

The solution, Andreoli says, depends on the individual patient and the severity of the problem. For starters, she tells patients to drink more water and avoid caffeine and alcohol, which are diuretics. She also says they should avoid fans and, if possible, use a humidifier during the day to slow down tear evaporation. Other solutions include lubricating eye drops, placing warm compresses on the lids and also taking supplements. “For some patients who have an oil imbalance, there’s pretty good evidence that if you take an omega-3 fatty acid, like fish oil, it can fix that component of it,” Andreoli says.

In severe cases, a drug called Restasis can help increase tear production.

Andreoli says that if patients are experiencing discomfort and blurry vision, they should be very clear when talking with their healthcare provider about what is happening. She says medical professionals may miss diagnosing dry eye because it’s not necessarily something that will show up in a test.

“I think it’s hard for some providers because you check somebody’s vision and it’s 20/20, and they can read the letters, and [you] say, ‘Oh, there must not be anything wrong,’” Andreoli says. “Sometimes it takes a patient saying, ‘I can read those, but at the end of the day I really can’t see.’”

For me, learning the cause of the problem was the biggest relief. The vision challenges—which I occasionally still have—are annoying, but they’re something I can manage, now that I’ve stopped worrying that my symptoms are leading to something far worse.