Pelvic floor physical therapy can improve quality of life for men and women

For years, Park Ridge resident Amanda Key, 24, planned her activities around bathroom access. She would avoid fun road trips to prevent accidents. On plane rides, she tried not to drink anything and always booked an aisle seat for a quick run to the bathroom.

Until she met physical therapist Tina Christie, Key didn’t realize how much her pelvic floor dysfunction affected her life. After just two weeks of pelvic floor physical therapy (PT) sessions with Christie at the Athletico Physical Therapy clinic in Park Ridge, Key saw significant progress, with less pain and anxiety, and increased bladder control. “My life has improved so much,” she says.

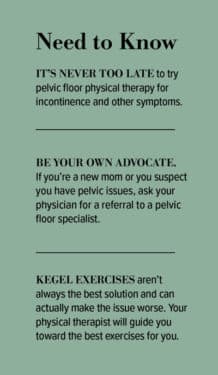

Though anyone can experience pelvic floor issues, women face the most challenges. Nearly one-quarter of women in the United States have experiences similar to Key’s, but many don’t seek help, feeling shame or embarrassment. Pregnancy and childbirth can weaken the pelvic floor, as can hormonal changes during menopause. That weakening leads to urinary incontinence and prolapse, when the pelvic organs drop from their normal positions.

And that’s where pelvic floor physical therapy makes a difference, teaching people how to identify what’s wrong, as well as vital exercises to strengthen and lengthen the pelvic muscles.

Suffering in silence

“Many women don’t know what is normal,” says Christie, women’s and men’s pelvic health program manager for Athletico Physical Therapy in Park Ridge. “If the medical providers aren’t asking the right questions, [people] think, ‘This is how my life is going to be now.’”

After giving birth, many people deal with urinary leakage every time they sneeze or do high-impact exercise.

The leakage happens because nerves, muscles, and connective tissues are stretched, compressed, or even torn during childbirth. Survivors of sexual assault and abuse, like Key, also may experience bladder, bowel, and alignment problems, in addition to pain with sexual activity. Trauma from car accidents or sports injuries contribute to pelvic floor issues, too.

“I was in this shame cycle around it,” Key says. “Tina showed me these simple exercises. She showed me how to control my muscles and how they are all connected.”

Key also benefitted from electrical stimulation techniques that sparked new connections in pelvic nerve endings. The therapy healed internal trigger points that had caused disabling pain in her hips and abdomen.

During weekly sessions, Key retrained her bladder and learned breathing techniques to avoid incontinence episodes at work. “I’ve lived with these issues since I was a child, but it turns out they were resolvable,” Key says. “I had to rebuild that mind/body connection.”

Christie, the youngest of four children, says pelvic floor health became very personal for her as she watched her aging mother struggle with severe pelvic organ prolapse. As a child, she wondered why her mother wore a girdle every day to hold her lower torso and pelvic bowl organs in place.

At one point, Christie says her mom consulted her male primary care physician about the prolapse. The doctor’s response: “Well, nobody has ever died from that.”

Inspired by her mother, Christie has devoted her entire career to pelvic floor PT, saying, “We need to do better.”

No simple solution

Today, pelvic floor PT is gaining in awareness and popularity. Now, when a person gives birth, more physicians ask pelvic health questions and offer referrals to specialists like Sheila Dugan, MD, professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at Rush University Medical Center’s Program for Abdominal and Pelvic Health.

Over the past two decades, the Rush pelvic health program has helped thousands of people, of all genders. The founders created a collaborative medical approach, with pelvic-related specialists — from colorectal surgeons to OB/GYNs and rehab providers — working together as a team.

“We wanted to fill a need for comprehensive care in this arena of complicated, challenging, and at times difficult-to-talk-about disorders of bowel, bladder, and sexual function,” Dugan says.

Too often, women with pain and incontinence hear that Kegel exercises will solve everything, but Kegels actually worsen some problems, says Kimberly Kenton, MD, chief of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery/urogynecology at Northwestern Medicine.

Sometimes, for example, the pain that postpartum moms experience causes them to strain and contract their internal muscles. Instead, they may need to lengthen and relax those muscles, Kenton says. Other treatments include heat therapy, abdominal exercises, yoga, and pool workouts. It’s never too late to start repairing the damage in a non-surgical way, she adds.

“The education has evolved, the research has evolved, but unfortunately, in the United States, we are behind the times,” Christie says. In some European countries, new moms receive up to 12 sessions with a physical therapist after delivery, as the standard practice of care. Recently, legislation has been proposed to also make this a standard of care in the U.S.

Meanwhile, growing awareness of pelvic health is bringing help and support to other populations, including men with prostate cancer and erectile dysfunction. Additionally, pelvic floor PT can treat a number of common complications associated with gender affirmation practices and surgeries. Pelvic floor specialists help with scar tissue, wound care, and post-operative bowel and bladder training.

“It’s about looking at the entire body, the entire kinetic chain and how that influences the pelvis and pelvic floor muscles,” Christie says. “I always say, if you have a pelvis, you’re going to benefit from this kind of information and care.”

That care changed Key’s life. “This has been such an empowering experience for me,” she says.