When tests reveal cancer probability, organ removal surgery can beat the odds

Hedda Hart-DeLara sat in her gynecologist’s office, checking boxes on a family history questionnaire. In her mid-30s, she hadn’t thought much about cancer, but the questions drew out memories of her mother, who died of cancer at age 50, and an aunt who had a full hysterectomy due to cancer.

Hart-DeLara’s mother, who was a smoker, died from lung cancer. “But they also found cancer in her ovaries,” she says. “This was the first time I’d been asked about ovarian cancer, so I checked that box.”

When Hart-DeLara’s gynecologist suggested a blood test to check for genetic mutations associated with cancer risk, the Chicago resident agreed.But Hart-DeLara says she wasn’t worried,even when the nurse requested that she come in to discuss her results.

Genetic mutations passed down through families — called inherited gene mutations or variants — drive an estimated 5% to 10% of cancers, according to the National Cancer Institute. These variants can interfere with cell signaling, causing cells to reproduce uncontrollably or to create misshapen versions of themselves. Specific mutations in the BRCA genes, for example, put female reproductive organs at greatest risk.

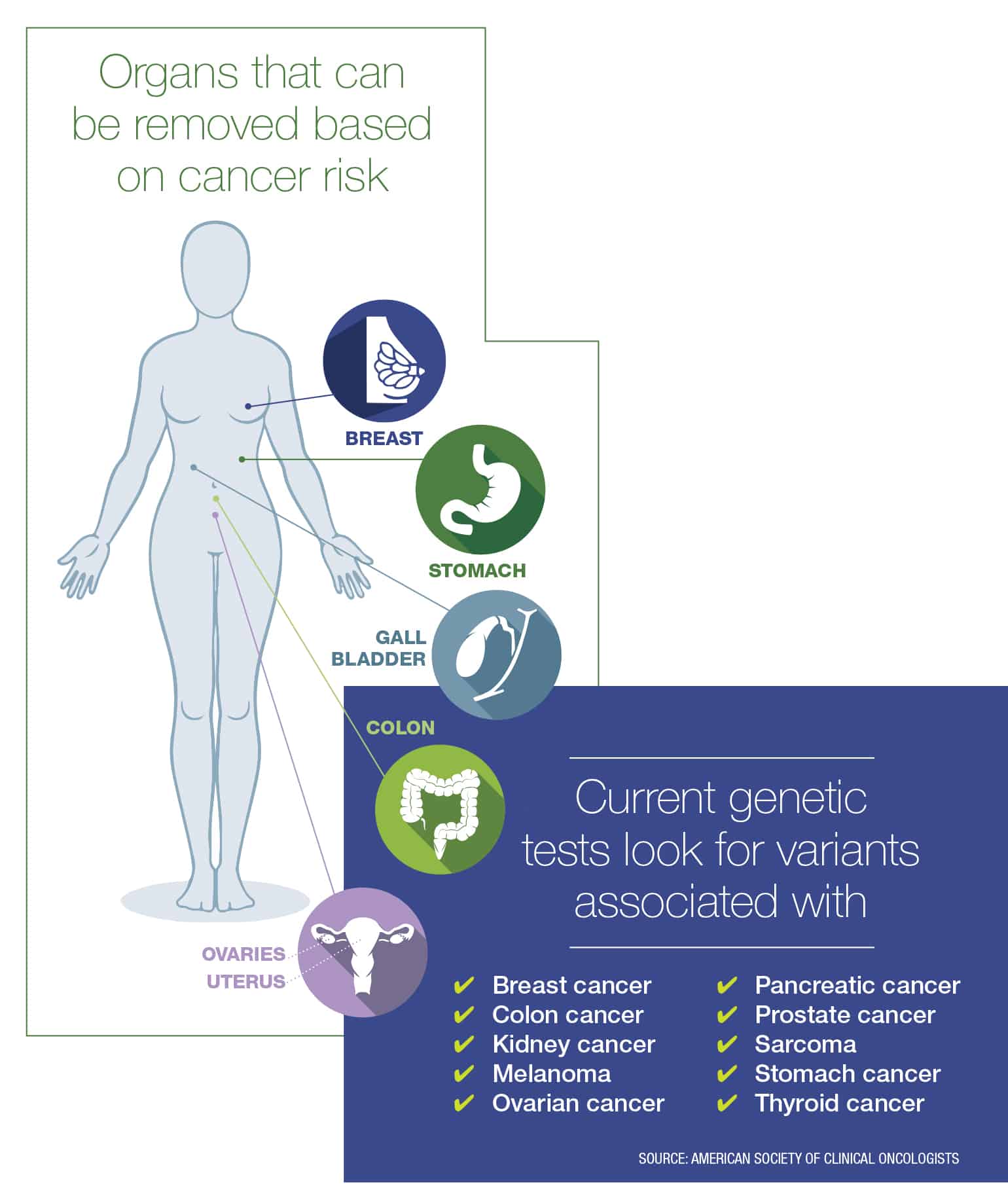

When a patient has a high risk of cancer due to a gene variant, they often have a choice — depending on the type of cancer — between undergoing frequent screenings to try to detect cancer early or removing the organ at risk to vastly reduce the cancer’s chance of occurring.

The latter option is called prophylactic surgery — removal of an organ while it’s still healthy in an attempt to prevent cancer. The theory is: Remove the organs, and reduce the risk.

“The question is: Do you want to prevent cancer or [try to] detect it early?”

Studies show that prophylactic double mastectomy reduces breast cancer risk by 95% in women with mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene, according to the National Cancer Institute. And for women who have a family history of breast cancer, prophylactic mastectomy reduces breast cancer risk by up to 90%.

“Certain features of those tissues — what their genetic makeup is — put them at risk. Part of it is the type of cells that make up that tissue,” says Julian Schink, MD, chief medical officer and gynecological oncologist at Cancer Treatment Centers of America, Chicago. “If you have these genetic mutations, you’re more susceptible to this bad programming.”

Nearly a decade ago, actress Angelina Jolie, whose mother died from ovarian cancer, underwent a double mastectomy after she found out she carried a BRCA1 mutation. Schink encourages his patients who test positive for the mutation to follow Jolie’s lead.

“If you have a BRCA1 mutation and you’re a woman, your lifetime risk of developing breast cancer is between 70% and 85%. And if you develop a BCRA-related breast cancer, you’re more likely than the general population to have triple negative breast cancer — a more aggressive breast cancer,” Schink says.

Surgery provides a clear-cut way to reduce cancer risk. However, Sonia Kupfer, MD, director of the gastrointestinal cancer risk and prevention clinic at UChicago Medicine, says, “We’re always thinking of ways we don’t have to do surgery. The question is: Do you want to prevent cancer or [try to] detect it early?”

Testing history

The process of determining genetic risk often starts with detailing an individual’s family history of cancer. But people also find out they carry gene variants through DNA testing companies, such as 23andMe.

Genetic counselor Eleanor Griffith, founder of Grey Genetics, offers remote genetic counseling to patients by phone or video to help them sort through their genetic risk factors.

“If we were dealing with something that weren’t related to health, it wouldn’t be as hard. Like if it were a chance of rain,” she says. If there were a 50% chance, you’d take an umbrella.

“It’s new for us to be thinking about health risks in this way, but it’s not new to be thinking about probabilities in general — even if we don’t always assign a number to those risks,” she adds. “If you go to cross the street and there’s a car coming, you make a calculated decision as to when it’s safe to cross. Maybe over time, this genetic risk information will feel more normal.”

Kupfer sees many patients with variants of the CDH1 gene, which greatly increases their risk for hereditary diffuse gastric cancer — a type of stomach cancer that’s difficult to detect. Of those patients, she estimates that 60% have opted for prophylactic surgery to have their stomach removed and digestive system rerouted.

One of Kupfer’s patients wanted genetic testing after his mother died of stomach cancer. When he tested positive for a CDH1 variant, he decided to have his stomach removed.

What may seem like extreme decisions to some don’t surprise Griffith. “Sometimes when someone has had that experience of watching someone they’re close to go through cancer, the idea of prophylactic surgery is not a hard one,” she says.

Kupfer adds, “The fact that we could figure out what was causing [the cancer] and who was at risk and that we could do something about it — that was very satisfying. But it’s not one-size-fits-all.”

Processing unknowns

Back in the gynecologist’s office, Hart-DeLara’s doctor delivered the news: She had a BRCA1 variant.

“I was just in shock,” Hart-DeLara says. Her gynecologist explained that while breast cancer is more frequently discovered in screenings, ovarian cancer gives few warning signs. Hart-DeLara’s doctor recommended that she consider prophylactic surgery to remove her ovaries and possibly undergo a mastectomy.

Hart-DeLara felt empowered to act, starting with more frequent cancer screenings. She joined a study at Northwestern University and had quarterly breast MRIs, ultrasounds and mammograms.

After the birth of her second child, she underwent prophylactic surgery to remove her ovaries and fallopian tubes. She now takes hormone replacement pills and is preparing for a double mastectomy.

“Some women really connect with their breasts, and I understand that. But mine have done everything they’re supposed to do,” Hart-DeLara says. She’s nursed two babies and laughs that she was wearing a low-cut shirt the night she met her husband. Now, she thinks of her breasts as “a constant, ticking time bomb that I have on my body. Having lost my mom, I don’t want to put my kids through that.”

This is Hart-DeLara’s normal now. “I just want to be there for my kids. Everything revolves around them,” she says. “I’m taking control. Because of this, I’m going to outlive my mom.”

And while the questions that led to her genetic test brought up painful memories, she’s grateful for the many more positive ones she has a chance to make.

Above image: Hedda Hart-DeLara’s two young children inspired her to choose prophylactic surgery. Photo by Coco Boardman. Infographic by Erin Sullivan. Originally published in the Spring/Summer 2020 issue.

An award-winning journalist, Katie has written for Chicago Health since 2016 and currently serves as Editor-in-Chief.